Viva Catedral!

A brief history of skiing in Bariloche.

While much of haute skiing culture in South America centers around Chile’s Valle Nevado and ritzy Portillo, as well as Las Leñas in Argentina’s wine region of Mendoza, the Argentinian mountain town of San Carlos de Bariloche has a richer history of European immigration and, therefore, deeper roots in mountaineering and skiing. Like Aspen and Chamonix, Bariloche, as it’s commonly known, was a real town long before it became a ski center.

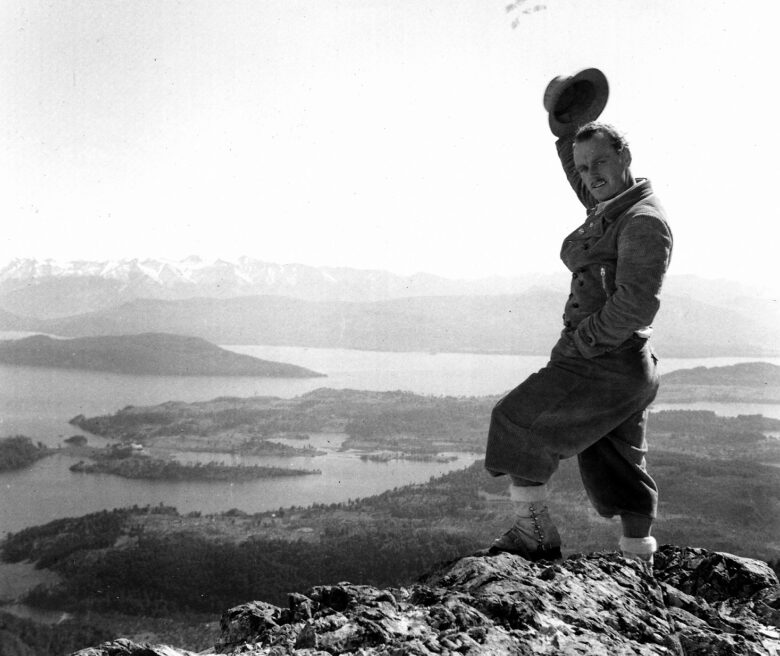

Photo top: In 1936, Innsbruck’s Hans Nöbl chose Cerro Catedral as the location for a

world-class ski resort. Courtesy Club Andino Bariloche.

The Early Years

The Cerro Catedral ski area’s birth and infancy are inextricably tied to Bariloche’s growth (translated from the Mapuche Indian dialect, the town’s name means “people from the other side of the mountain”). The mountain Cerro Catedral was named for its resemblance to a cathedral.

Argentina, like North America, is a melting pot, especially Bariloche. German and Swiss migrants first arrived in the town before the 20th century dawned, bringing many architectural, cultural and gastronomic influences that came to define the region.

Ruben Macaya grew up skiing on Cerro Catedral and raced for Argentina in the late 1960s. He later coached the U.S. Ski Team at the 1984 Winter Olympics, then coached in Aspen and Vail and for decades was the head coach for the Sun Valley race program. Macaya explains that the first European settlers arrived at Bariloche in 1891. Most of these folks arrived via the glacial lakes and Indian trails over the low pass from Chile, which had developed a thriving German community composed mostly of liberal refugees from the failed European revolutions of 1848.

Macaya relates that in 1903, Francisco Pascasio Moreno, a pioneering scientist and explorer, donated land near Bariloche for a national park. In 1922 Parque Nacional de Sur was established as the first national park in South America and the third in the Americas. Argentina’s powerful national parks office planned to make Bariloche into a touristy, European-looking town using its own public funds.

Beginning in 1913, a German named Ricardo Roth had the concession to the road and the boats that transported people between Chile and Bariloche, a four- or five-day trip. On the Argentine side was another German, shop owner Carlos Weitherholdt, now considered the founder of San Carlos de Bariloche, which sits at an elevation of 2,600 feet on the south shore of Lake Nahuel Huapi. In the other direction, toward Buenos Aires and the Atlantic, stretched the desert prairie, the Pampas. Crossing the Pampas via stagecoach or ox cart took four to six weeks—it was like crossing the Great Plains in North America.

Just before World War I, construction began on a narrow-gauge railroad from Buenos Aires to Bariloche and, eventually, to the Pacific coast. But the war halted investment by European and American financiers. Argentina profited from the war mainly by exporting beef and horses for use by European armies. Osvaldo Ancinas, the Bariloche-born Olympic skier who settled in Squaw Valley in 1960, jokes that Argentina raises “not only the fastest horses, but the best-tasting horses!”

After the war, Austrians, Italians and Slovenians arrived, fleeing the political and financial chaos accompanying the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. At Bariloche they found a region as gorgeous as their beloved Alps and Dolomites.

The railroad from Buenos Aires finally reached Bariloche in 1934. At that point, wealthy folks from the city made the town and its surrounding mountains a holiday getaway.

By the 1940s, Bariloche had grown from a remote regional outpost of 1,000 inhabitants into a bustling city of 5,000 residents and Argentina’s epicenter of skiing and hiking, with around 55,000 annual visitors. After World War II another influx of Europeans—refugees from both Axis and Allied nations—came to start a new life in a setting that felt European.

Now close to a quarter of a million inhabitants live in the region (Bariloche has a permanent population of about 145,000), and as the gateway to Cerro Catedral, the city welcomes more than 600,000 tourists each winter alone. The Alpine influence still shines brightly, from torchlight descents down Catedral’s slopes during the annual Winter Festival (Fiesta de la Nieve) to the veal Milanese lunches pounded out for diners in the mountain refugios to locally made chocolates that would knock the socks off Ferrero Rocher.

A Ski Area Is Born

Juan Javier Neumeyer was one of the first physicians to establish a practice in Bariloche. Argentine-born to Swiss parents, he spent several years in Switzerland and became an accomplished climber and skier. In 1930, Neumeyer introduced the Bavarian gymnast and climber Otto Meiling to skiing; their climbing partners included Reynaldo Knapp, a British pilot who set up a tour-guiding service, and Swiss-trained surveyor Emilio Frey.

In 1931, these four friends founded the Club Andino de Bariloche to promote mountain sports. In 1934, Frey was appointed the first superintendent of Nahuel Huapi National Park. The four founders built seven refugios, the first one on 4,500-foot Cerro Otto, four miles west of Bariloche. Today, all seven huts continue to shelter skiers and climbers throughout the millions of acres of wilderness in both summer and winter.

Catedral’s roots were planted shortly thereafter. In 1936 the National Parks Directorate signed a five-year contract with Innsbruck-born skier Hans Nöbl to scout a suitable location near Bariloche for a winter resort of international caliber. Nöbl came well-recommended: Working for the Agnelli family, owners of Fiat, he had helped manage the launch of Italy’s Sestriere ski resort in 1934 and then became head of its ski school. According to Andreas Praher, author of Austrian Skiing in the Nazi Era, Nöbl avoided entanglement with the Nazi element while he was in the Innsbruck Ski Club, but got the Sestriere gig after teaching Mussolini’s sons to ski.

Macaya explains that Nöbl came to Buenos Aires and charmed the wealthy skiers there. Arriving in Bariloche, he surveyed

several potential sites for the big resort. “There were two other locations he considered, but at one of them you would have had to take a boat to get to the ski resort, and the other was closer to the Chilean border than to Bariloche, so they ruled it out,” explains Roberto Taddeo, nephew of Osvaldo Ancinas and a well-known ski coach.

Bariloche native Vicente Ojeda, who grew up to be a downhill ski champion, remembers that “Nöbl was tall and very skinny with big, blond hair. He was a classy dresser and an elegant skier. [Local] people didn’t really like him; he was arrogant and business-like, pinching money wherever he could, so people were a little wary of him. But he did a lot for the town of Bariloche, and we got Catedral because of him.”

Nöbl’s eventual choice bore sweet fruit almost immediately. In 1938—the year he settled full time in Bariloche—he directed the design of a tram to Cerro Catedral’s 6,300-foot summit. The tram parts were manufactured in Italy before World War II broke out but sat on a dock until trade resumed in 1945. In 1940 the first drag lifts were installed at Catedral, with financing arranged by Dr. Antonio Lynch, president of the Club Argentino de Ski (CAS), founded in 1938. The lifts ran

from the base area to an elevation of 5,600 feet. Two years later, the first ski lodge on Cerro Catedral was completed (managed by CAS), on what was then the highest point of the ski area. It was named Refugio Lynch, and it was there that three-year-old Ruben Macaya came to live with his mother, who worked as the hostel’s chef and housekeeping manager for the concessionaire, Carlos Oertle.

“Oertle ended up being like a grandfather to me,” Macaya says. “When [my mother] got the job cooking at Refugio Lynch, it was a five-star lodge. The whole thing was unbelievable. All the chairs and sofas were cowhide, hand hewn and hand painted, and there were paintings from famous European and South American [artists]. The place was first class. When my mom got there, she said, ‘Oh, my God! Where have I landed? This

place is fantastic.’ It had beds in three big rooms, one for women and two for men. It had room for 15 women and 28 men.”

The resort lay within the national park, and development was funded largely by the national parks office. Park employees built the roads and infrastructure, at times carrying loads up the mountain on foot. The Argentinian government also invited private investment for hotels within the park. In one case, an Italian dowager, the Contessa Gambona, built the Hotel Catedral, and in 1944 the first base accommodations were opened to Buenos Aires elite.

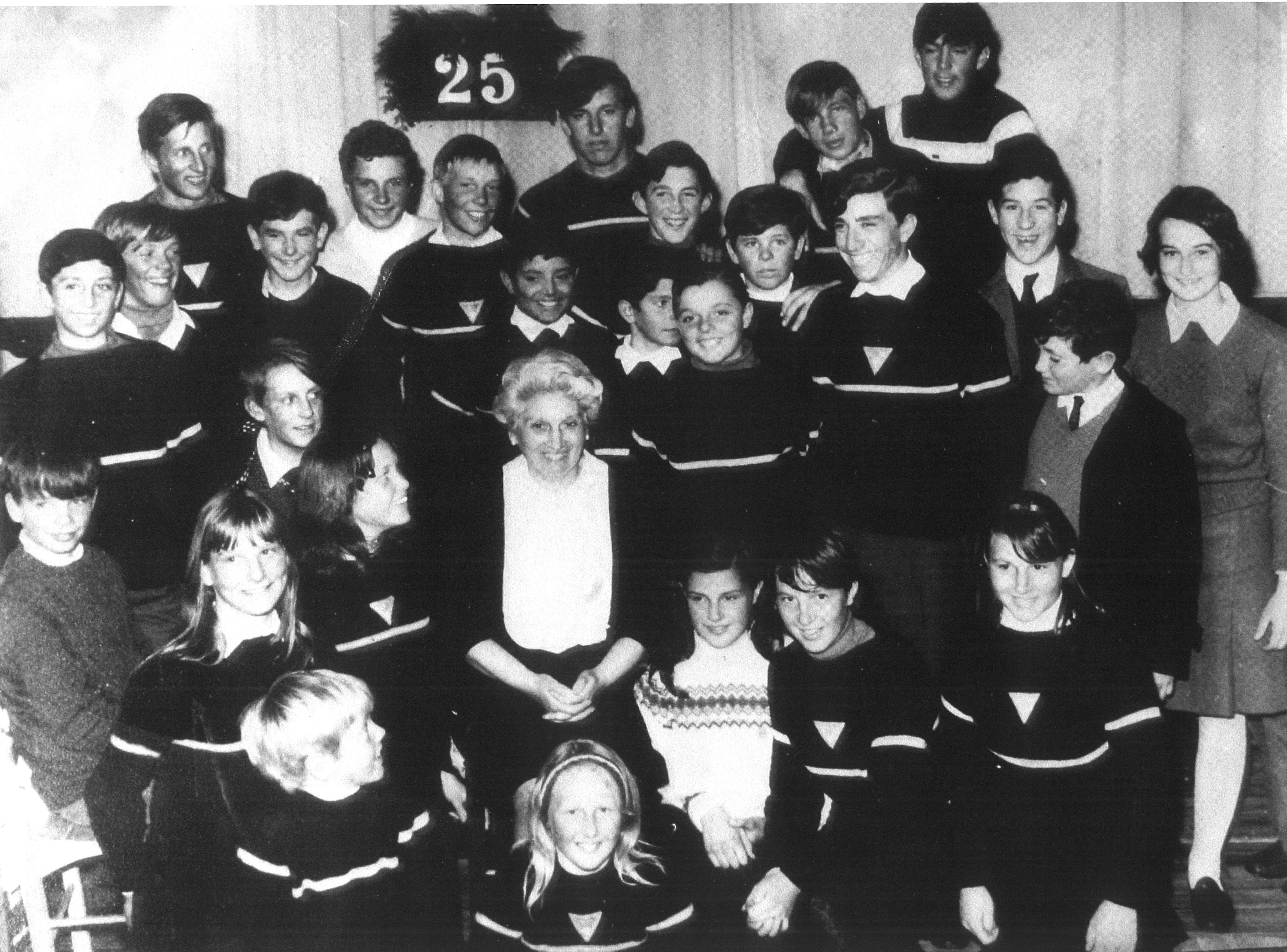

Catalina Reynal, La Madrina (the Godmother)

Osvaldo Ancinas recalls, “I started skiing in August 1944, when I was 10 years old. We had a 1,500-meter surface lift, and the old cable car that was installed in 1950 took us up. I started skiing at the school of Catalina Reynal.” Reynal came from a wealthy cattle-ranching family, with thousands of acres on the Pampas. She became concerned that the children of the community couldn’t afford to ski. “She wanted the children of

Bariloche to learn,” Ancinas says. “So she’d take all the kids up to the mountain in a truck with a cover on it. They had 18 feet of snow at the bottom of the mountain. She always told me Bariloche needed to keep the kids busy with skiing. Her friend Antonio Pelligrino got together the skis and boots and such. What a wonderful woman! She and Antonio were how I learned to love to ski. She introduced me to the sport I still love today.”

Macaya once visited Reynal at her home in Buenos Aires. “I asked her what drove her to help the kids,” he recalls. “She said that at the time, when you went to Hotel Catedral it was just the wealthy elite of Buenos Aires, and that the locals were shut out. ‘How can the locals learn to ski if we don’t help them?’ She got instructors to work with kids on the mountain. She was a visionary in that regard.”

Cosmopolitan Ski School

The first two ski instructors at Catedral were Nöbl and Meiling. “They did not like each other,” Macaya says. “Hans was more interested in big money and exposure, whereas Meiling was a real mountain man—he despised the wealthy people of Buenos Aires. His school was for the people, whereas Hans’s was more for the elites.”

At the end of World War II, Dinko Bertoncelj was 16 years old. When his father was shot, he fled from Slovenia to Austria and spent two years in a British-run refugee camp. He managed to climb and ski and was encouraged by an Austrian coach to imigrate to Argentina. Bertoncelj was still a teenager when he landed in Bariloche but soon became a leader in the mountaineering community, putting up first ascents and joining expeditions to the Himalaya and Antarctica.

“His first job was running the boilers at the Hotel Catedral,” says Macaya. “He skied with the family that owned the concessions.” Bertoncelj traveled back to Austria to get certified in ski instruction at St. Christof and also taught in the United States before returning to Bariloche. “By about 1960, he was head of the CAS ski school,” Macaya says. “There were so many Europeans in Bariloche, they were teaching each other to be instructors.” Eventually Bertoncelj took charge of ski instruction for the Argentine army.

Ancinas remembers taking lessons from a Polish instructor, Andres Nowortya. “He’d say, ‘You got to bend your knees some more or I’m not gonna teach you!’ And then we had another coach, he’d say, ‘We’re going to the mountain to be away from everybody and be closer to God.’ And we walked. We carried everything by foot. Even as a small boy, standing up with snow up to my chest! And we became the first members of the ski patrol in 1950–51. I was 16.”

Boom Years

The ski scene at Cerro Catedral boomed in the 1950s. Then airline service to Bariloche began in 1967.

“Billy Reynal [nephew of Catalina] was a genius of marketing,” says Roberto Taddeo. Reynal, who had an American mother, left school early to work in the oil business. He loved to ski and loved airplanes, so he acquired Austral Airlines and organized a holding company, Lagos del Sur. Through this company, Reynal developed several new chairlifts on Catedral, which opened a vast bowl east of Refugio Lynch. Then he created Sol Jet, a tourist company, and built several mid-price hotels both in the city and at the ski area.

His goal was to democratize skiing, making it accessible to a middle-class market. Austral flew passenger routes day and night—shuttling skiers from Buenos Aires to stay in Lagos del Sur hotels in Bariloche and Catedral. But Austral competed with the government-owned Aerolineas Argentinas, and in 1980 the country’s military dictatorship nationalized Reynal’s businesses. Reynal left to live in the U.S. For a decade, the management of Catedral was split chaotically between two companies, one controlled by the dictatorship. Civilian rule returned after the 1982 Falklands War. Eventually Reynal and his son returned, and they resumed control of Catedral from 1997 to 2001.

Bariloche Today

“When I left Bariloche in 1960, there were only 25,000 people living there,” says Ancinas. “Now there are 160,000. A friend told me recently there were 21,000 people skiing on Catedral one day. It’s a big change.”

Ancinas traveled to his hometown last spring to celebrate his 90th birthday on the mountain. While there, he realized that some of the hazards have changed. “Now at the Refugio Lynch, they ski by at 100 miles an hour!” he says. “When I was young, you had to watch out because the foxes would steal your lunch!”

“Yes!” laughs Macaya. “Once, years ago, the foxes actually ate through the phone cables. They ate Osvaldo’s long thongs while he was having lunch at the top of the mountain.”

Catedral isn’t the only ski area near Bariloche—Winter Park is the “town” lift network on close-in Cerro Otto. But those who grew up there insist Catedral is by far the most beautiful. Ancinas calls it the most beautiful ski resort in the world.

By day skiers can shred 1,500 acres of in-bounds terrain and another 1,500 acres of backcountry, much of it with stunning views of colossal glacially carved lakes dotted with islands, smaller Alpine lakes, thousand-year-old deciduous and evergreen forests, and volcanos in both Chile and Argentina. (They still occasionally erupt.) Bootpack through a notch off the summit’s backside to access millions of acres of pristine national park. Sunrises and sunsets ignite the silhouetted mountains of Patagonia in a fiery burst of red, orange and gold. And by night, a billion stars illuminate the lazy haze of the Milky Way.

Jay Flemma practices law and recently moved from upstate New York to Boise, Idaho. He also writes about golf for websites owned by ABC, CBS and NBC.