Big-Box Ski Stores: What Killed Them?

Family-owned specialty ski shops have survived the threat of discount sporting-goods chains. How did that happen?

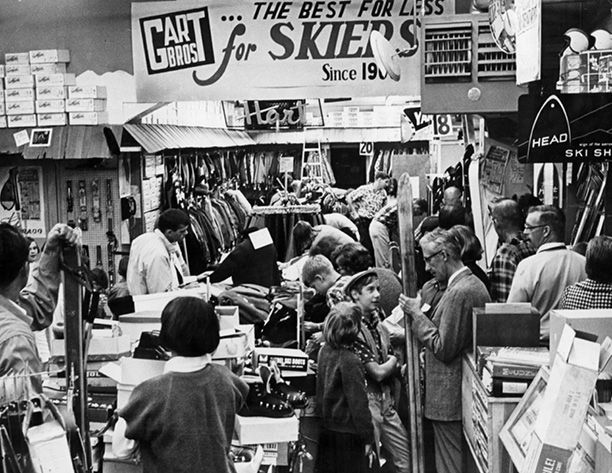

Back in the 1970s and ’80s, independent ski shops faced vigorous competition from so-called “big-box” or discount chains like Herman’s World of Sporting Goods, Morrie Mages Sports, Big 5 Sporting Goods and Gart Brothers. Because they bought so much stuff, these huge stores enjoyed the lowest cost from their suppliers, allowing them to promote sale prices to consumers that indie ski specialists couldn’t match. Moreover, because they also sold golf, tennis, running and team-sports gear, they could better endure a low-snow winter, so manufacturers viewed them as reliable customers.

Photo top: The Gart Brothers Sports Castle once ruled the Denver market, pulling huge crowds during late-summer sales. Publicity photo.

Wholesale price discounting based on unit volume favored stores that focused on entry-level price points, where unit costs were rock bottom. Big buyers demanded some measure of exclusivity, so ski factories offered “special make-up” skis, or SMUS, with different cosmetics for each store in a region. Thus, the cheapest beginner ski could be sold under the name Rossignol G-Wiz at Gart Brothers in Denver and under the name Rossignol C-Master at cross-town rival Dave Cook Sporting Goods. This encouraged aggressive price competition on ski-boot-binding packages; it also allowed a store to offer a tricky low-price guarantee, with confidence that no one anywhere else was selling a G-Wiz model. No stand-alone specialist could swim in these waters, squeezing them out of a big chunk of the total market.

Existential threat?

The specialists correctly perceived the chains as an existential threat. They could sell boot-fitting expertise and counter some of the low-end price competition with leasing programs for kids, but they needed better wholesale prices to survive. So they created a patchwork of commercial alliances (buying groups) that consolidated purchasing power to earn wholesale discounts comparable to what the chains got. By the mid-1980s, five nationwide retailer buying groups represented a few hundred specialty shops, but even taken as a whole they accounted for only about 20 percent of the total retail community. The regional sporting-goods chains still owned at least a 25 percent share and were growing.

Skip forward to today and that entire big-box retail channel has all but vanished. In the West, Oshman’s, Sport Chalet, Sunset, Wolfe’s, Cook’s and Gart’s are gone. In the East, Herman’s, which once could order 75,000 pairs of a single low-price binding, is long gone, joined in the retail afterlife by the likes of Ski Market and Bavarian Village. While a few big-box sports chains remain, such as Big 5, Scheels and REI, their collective impact on retail ski sales today is negligible.

The specialty retail community hasn’t fared much better, losing hundreds of independent shops to acquisition, attrition and the intensifying unaffordability of skiing for their middle-class customers. Meanwhile, all the ski-dependent buying groups have coalesced into a single entity, Winter Sports Retailers, that convenes what remains of a national ski trade show. The specialists have won the war, but the body count was high. The biggest entities in ski retail now are “chains” owned by the resort conglomerates: Vail Resorts reportedly operates some 500 stores, and Alterra about 300.

Death of the entry-level ski

What calamity befell the sporting-goods chains to all but kill off the channel? Essentially, they gradually lost their grip on entry-level skiers, who were lured away by the low-risk convenience of renting or leasing elsewhere. By the time this wave of beginners was ready to buy their own kit, the Internet swept up the bulk of discounted low-end sales. First-time skiers drop out at a staggering 85 percent clip. The 15 percent who go on to become addicted to the sport eventually learn the importance of boot fitting, which has always been the core service of the specialty shop.

With the disappearance of an entry-level market came the inversion of the ski-product pyramid. In the ’80s, a sprawling base of inexpensive models supported a robust, higher-margin mid-market topped by a tiny elite tier of race skis. But several phenomena upset what proved to be a delicate ecosystem. The chains began to consolidate: Sunset bought Wolfe’s, Gart’s acquired arch-rival Cook’s and so on. That reduced the need for so many iterations of the cheap ski. Most of the multi-location, regional powerhouses wanted to fatten the bottom line by selling higher-margin “performance” equipment, but a history of dependence on pure price promotion, along with lackluster staff training, made it hard to lure traditional customers into a more profitable model.

Three factors made possible the complete inversion of the product pyramid. To produce more high-profit expensive skis, ski marketeers first had to concoct a larger population of experts, a feat Salomon pulled off with its second ski collection, which debuted in the early ’90s. Salomon declared that there wasn’t just one archetype of the expert skier but three: the racer, the mogul skier and the technician/instructor, each requiring its own model type. By co-promoting the mogul skier and the instructor alongside the racer, Salomon demonstrated that a supplier could rationalize a whole new family of ski models just by identifying a new skier type. The complete inversion of the ski product pyramid by the end of the decade was set in motion by Salomon’s model proliferation at the summit of the old product ziggurat.

Shaped skis, fat skis

The second big swing in product segmentation arrived in the mid-’90s with the shaped-ski phenomenon. It only took two years for carving skis to render skinny skis obsolete, which allowed the vanguard of the carving movement to reset the entire language of ski segmentation. The pricing hierarchy that used to be organized by skier ability instead flattened out, as the new product line was instead segmented by the type of carving the skier preferred.

This madness prevailed for a few seasons before the third transformative factor, the fat ski, went from curio to the dominant genre in the American market. The adoption of waist width as a form of model segmentation allowed ski makers to anoint a minimum of seven unisex top-of-the-line models in place of two and create a parallel universe of women’s models. Further fragmentation of the market into twin-tip, pipe-and-park archetypes and various interpretations of a touring or sidecountry ski continued the multiplication of high-end models, while entry-level offerings were distilled down to one or two options. The inversion of the ’80s product pyramid was complete.

The redirection of the first price-point consumer into the rental market had caused a predictable dip in retail sales that wasn’t easily recouped. The innovations associated with carving and fat skis allowed the ski trade to replace the unit loss in the eroding low end with a richer product mix that delivered higher profits. The brands that survived the 1990s learned a lesson that the chain stores had not: If your core market is shrinking, more discounting doesn’t work. On the contrary, you have to extract the most value you can from every sale.

As for the question of which side won the war between specialty retailers and chains, considering the attrition that’s decimated the ranks of both, it would be hard for either side to conclusively declare victory. Both communities have seen their margins trimmed by the scourge of the internet, where the de facto retail price is set by some of the worst actors in the market. In the ’80s, specialists were worried that the chains would undercut their margins; now both channels are at the mercy of the lowest price posted on the web, helpfully located at the top of any ski-related search results.

The ubiquity of the internet requires retailers of every stripe to participate at some level, but investing heavily in an online presence is as likely to sink a shop’s fortunes as buoy them. The internet is a soulless entity that eats its own young; even cornerstone online ski peddlers are rumored to be in financial difficulty. Of course, while all ski brands maintain an internet presence for informational/promotional purposes, some sell online directly to the skiing public, in parallel to dealer outlets. Whether a given ski brand’s pricing policies favors chains or specialty stores or websites is more or less moot, given that the brand itself is in direct competition with them all.

How One Specialty Ski Shop Became a Specialty Chain

Christy Sports was founded in 1958 by Ed and Gale Crist as a single-location, family-run store in Lakewood, Colorado, on the west side of Denver. Since then, thousands of other small to mid-size specialty operations have gone to their great reward in retail heaven, while Christy Sports’ shingle now hangs outside more than 60 ski-centric establishments across Colorado, Montana, Utah and Washington. They are one of the few surviving regional chains.

Christy Sports was founded in 1958 by Ed and Gale Crist as a single-location, family-run store in Lakewood, Colorado, on the west side of Denver. Since then, thousands of other small to mid-size specialty operations have gone to their great reward in retail heaven, while Christy Sports’ shingle now hangs outside more than 60 ski-centric establishments across Colorado, Montana, Utah and Washington. They are one of the few surviving regional chains.

Christy’s first forays into the mountains were to the relatively adjacent Copper Mountain and Vail, where the store planted its flag before these resorts exploded into giant corporations. Christy’s moved into the big time when it absorbed SportStalker, founded in 1972 by Ben Hambleton, which occupied premium locations at the gondola bases in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, and Snowbird, Utah. Following a pattern it would repeat again and again across Colorado, Christy’s would retain the name of the shops it acquired, capitalizing on their established reputations as top specialists.

But while the public face of the acquired shops didn’t change, where management decisions were made did. Centralized buying that homogenizes a chain’s model selection and neuters on-the-ground decision-making doesn’t normally attract top talent at the shop level, but Christy’s longtime buyer Craig Peterson had seen this edifice being erected store by store and tried to provide a flexible presentation rather than cramming a fixed menu into every location.

In 2002, after the founding families sold a controlling interest to the aptly named Patrick O’Winter, Christy’s extended its empire into Washington and New Mexico. In 2019, private equity firm TZP Group became a partner in the enterprise.

Nothing grows to the moon (except, perhaps, Amazon), and Christy’s signaled it was perhaps over-extended when it shuttered the New Mexico holdings this past winter, including a recently acquired Boot Doctors location. As Christy’s has been passed from one boardroom’s management team to another’s, its venerable locations have strayed from the ground-up identities that once gave them cachet. As other multi-location outfits have discovered, homogenization of the product creates a tough environment for retaining the personnel that make a specialty shop feel special.

Contributor Jackson Hogen participated in standards development as part of his career at Salomon, 1978–87. He wrote about those standards in the January-February 2023 issue of Skiing History.