1937: Durrance Down Under

One southern winter, Dick Durrance, James Laughlin and the Bradley brothers conquered New Zealand and Australia.

During the summer of 1937, two American ski teams competed outside the U.S. One team raced in Chile in the first Pan-American Skiing Championship (see “Pan-American Skiing Championships,” November–December 2023). That team consisted of Seattle’s Don Fraser and five members of the Dartmouth ski team, three of whom were on the 1936 Olympic team: Fraser, Warren Chivers and Ted Hunter.

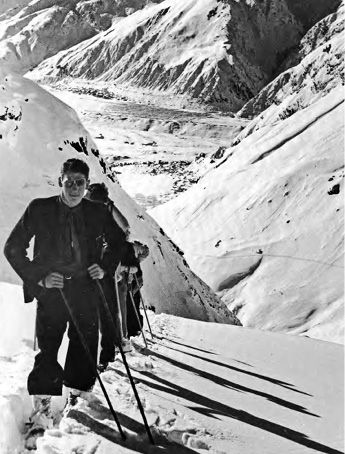

Photo above: Dick Durrance on the downhill course, 1937. Steve Bradley photo.

A second American team went to Australia and New Zealand for a summer full of skiing, competing in both the 1937 Australian and New Zealand championships. This squad included three members of Dartmouth’s ski team—Dick Durrance plus Dave and Steve Bradley—along with James Laughlin of Harvard.

Durrance was the most successful American-born ski racer in the 1930s. He led the 1936 U.S. Olympic team and Dartmouth’s ski team, and won the first Harriman Cup tournament at Sun Valley in March 1937, winning both the downhill and slalom and beating the likes of downhill world champion Walter Prager (his Dartmouth coach) and Alf Engen.

As Durrance told the story in his book The Man on the Medal, not long after the Harriman Cup races, he got a surprise call “from a complete stranger with an amazing proposition. ... How would you feel about going skiing in New Zealand and Australia?” The stranger was Laughlin, a student at Harvard who had learned to ski above Geneva, Switzerland, and in St. Anton, Austrian, raced a bit and acquired a taste for high-mountain touring. Laughlin’s family owned a steel mill in Pittsburgh. He had money and offered to pay for the trip.

Durrance seized the opportunity and suggested asking his Dartmouth teammates, Dave and Steve Bradley, to join them. Durrance and the Bradley brothers were four-way skiers, competing in downhill, slalom, jumping and langlauf (cross-country). Steve finished fourth in jumping and combined at the Eastern Intercollegiate Ski Union Championships. At six-foot one, he towered over his kid brother; Dave, a year younger, was the 1936 U.S. Eastern Champion in Nordic combined and captain of the 1937–38 Dartmouth ski team. Laughlin, at six-foot five, and Durrance, at five-foot six, made an unlikely duo.

Durrance asked Roland Palmedo, president of the Amateur Ski Club of New York, to help certify the group as an official U.S. team through the American Ski Association. As the first American team to compete Down Under, they called themselves the “Official U.S. Expeditionary Alpine and Nordic Team.” Getting to the Southern Hemisphere took more than three weeks on the steamship Mariposa. Durrance, an art major at Dartmouth who would go on to a career in photography and film, brought his Leica. So did Steve Bradley. They even brought darkroom equipment.

Skiing with the Kiwis

On New Zealand’s North Island, the travelers were hosted by the Ruapehu Ski Club. They were taken by a half-track to a mountain hut and skied several days in unrelenting fog, dealing with “armor-plated ice,” according to Laughlin, writing in the American Ski Annual, 1938. They held a few races, in which the Kiwis weren’t serious, “but we did have a great time with them,” Laughlin wrote. “They were good company.” The highlight was the ascent of Mount Ruapehu at the end of the stay, where the skiers emerged above the clouds onto a vast, smooth glacier leading to an ice-set crater of deepest emerald green, with a panoramic view from the summit. The Ruapehu Ski Club made them honorary members, and the Americans were touched by the gesture.

On the South Island, they traveled to Mount Cook and stayed at the Ball Hut, the headquarters and social center for the New Zealand National Championships, and climbed to the Ball Glacier, riddled with crevasses and threatened by avalanches. The Kiwi skiers “seemed blithely unconcerned with crevasses,” Laughlin wrote.

The championship races took place at the top of the glacier. The South Islanders were much better skiers than their North Island counterparts, and the Americans had a great time. They built a 30-meter ski jump to hold a four-way New Zealand championship at the top of the mountain.

The two-mile-long downhill course covered 2,500 feet of vertical and was marked with little paper flags. “It was pretty much guessing yourself down through the crevasses and hoping for the best,” wrote Durrance. He won the downhill, while Laughlin was third and the Bradleys came in fifth and sixth. Harry Wigley (Kiwi team captain and a pioneer aviator) and Brian McMillan (the top Kiwi jumper) finished second and fourth. As Laughlin wrote, “Durrance won cleanly, running the sweet, brainy, faultless sort of race that only he among us can, cutting the course record nearly in half.”

Durrance designed the slalom course. According to Dave Bradley, writing in the American Ski Annual 1938, it was “an excellent sequence of exacting situations, which included a series of sweet S corners at the top, an unavoidably icy descent, more fast turns and a six-gated flush just before the finish.” Durrance, continued Bradley, “thrilled the audience that had come up ... to watch him, having heard of his European record.”

In slalom his technique and incredible muscular speed put him far ahead of all the rest of us. Each of his runs brought gasps, a hush and then cheers. He ran in his new low position of complete vorlage, doing the sharper turns over a pole pivot, choosing infallible lines, and always leading with the chin—that is, with the head and shoulders always down in front, literally pulling his body and skis along behind them. He was greased lightning in the tightest flushes, and his sight judgment of traps, checks and lines was a joy to watch.

Durrance won both slalom runs, followed by Dave Bradley. In the jumping event, Durrance had the longest distance, at 30 meters, but he lost on style points to the Bradleys. The cross-country race was canceled because of weather.

According to Laughlin, the Americans’ biggest take-away from their time in New Zealand was the international camaraderie that develops from skiing. “Young men and beer: a good time was had by all.” He added,

We weren’t skiing against the New Zealanders but with them. It was that way from the first. We skied with them. We lived with them. We borrowed each other’s things. We taught them Durrance’s stick turns, and they showed us the best lines to take on their courses. It was like that. The figures showed that we beat New Zealand, but New Zealand won us completely.

Laughlin closed by saying the Americans would remember "the friends we made, the cities we saw, the nosedives we took in the unfamiliar deep snow—there was nothing in the whole visit we would want to forget. ...There is a place down under the South Seas where summer is winter and the skiing grounds are as good as all but the most expert skiers could ask for. New Zealand does take imagination, but it isn’t a dream. It is a real place to ski."

Injuries in the Land of Oz

The Americans spent five amazing weeks in Australia, hosted by the Ski Club of Sydney “in the Down Under style,” Durrance reported. “You try to drink more than I can, and I’ll prove that you can’t. We became extremely good pals.”

The team competed in three tournaments: the national championships and Inter-Dominion and Inter-State matches. The best snowfall of the season covered the Charlotte Pass ski area “with an abundance of snow for racing purposes,” according to Durrance.

The Americans first competed at Mount Buller, in the U.S.A.–Victoria match, although Laughlin and Dave Bradley suffered injuries that limited their racing. On the way to the ski area, the car in which Bradley was riding got into a head-on collision. His hand went through the windshield, and he cut a tendon in his thumb. Dave spent three weeks in the hospital, where he met more “new friends than the boys who were still racing,” wrote Durrance.

Meanwhile, Laughlin broke his collarbone when he hit a pile of rocks in the downhill race at Mount Buller. That ended his ski tour, but, Durrance wrote, he met “an amusing Australian girl named Toodles, whose parents had a beach house, where he had three weeks of pleasant R&R.” Both Laughlin and Dave Bradley got medical treatment in Melbourne, then Laughlin went home. Durrance and Steve Bradley went to the next tournament and were later joined by Dave.

But before they left Mount Buller, Durrance won the two-run downhill, likely establishing “a world’s record for downhill races” (according to Dave Bradley) by finishing the first run in 24 seconds. Laughlin and Steve Bradley were second and third. Durrance also won the slalom, followed by Australian Tom Mitchell and Steve Bradley.

The Americans next competed in the Australian championships, held at Mount Kosciuszko. Durrance and Steve Bradley, the last men standing, did little training for these races, instead spending their time developing yards of Leica film. Australia, New Zealand and the U.S. each entered two-man teams that would run in four events each.

The chalet where the racers stayed at Mount Kosciuszko was 18 miles from the highway. They skied into the chalet, while a half-track carried their luggage. The three Americans stayed in a small room with two Austrians and a Norwegian, which they called “the League of Nations Chambers,” according to Dave Bradley, because of the “endless riotous discussions which took place there.” However, its conditions were “scarcely flattering to that dignified body,” Bradley wrote. Wet clothes were hung everywhere; the floor was knee deep in clothes, boots, cameras, packs and suitcases, and “every bed in a similar unhappy state.”

Durrance won the slalom, wowing the fans, and was followed by the Austrian Ernst von Glasersfeld (skiing as an individual, not part of a team). According to Walter Annabel, writing in the Australian and New Zealand Ski Year Book:

Durrance’s running stirred the spectators to great enthusiasm and was applauded most of the time he was in action. He rarely was more than two feet from the snow in a deep crouch. Always watching two pairs of flags ahead, he showed perfect rhythm of rise and drop in each turn, and at one point took a 30-feet jump in each run.

Meanwhile, von Glasersfeld “gave a classic exhibition of true Arlberg running,” Annabel noted.

The ski jump was dangerously flat and narrow, and the event was won by Durrance with “a beautiful and startling ‘aero-dynamic’ style,” according to Annabel. Steve Bradley, who hurt his knee during the competition, place second, exhibiting “a delightful performance of graceful jumping.” Dave Bradley won the 10-mile cross-country race, with his arm in a cast, giving “an accomplished exhibition of langlauf” and beating Durrance “by the narrowest of margins,” wrote Annabel. Australian George Day was third.

The downhill course on Mount Townsend was steep and fast, although the sun thawed the lower part of the course, making the snow almost too slow for a championship downhill. Dave Bradley reported that the course was a six-mile trek each way, involving the ascent of three substantial ridges. As was true for most downhill races in those days, there were no control gates, and each racer chose his own route of descent. Von Glasersfeld, wrote Annabel, “was going quite fast in his usual nonchalant style.” Annabel noted that Durrance appeared tired after the prior day’s jumping and cross-country events and was beaten by von Glasersfeld by a few seconds. Australia’s Pattinson brothers finished third and fourth (a triumph for Australia), followed by Brian McMillan from New Zealand, then Steve Bradley, who finished fifth in spite of his knee injury.

Durrance, the Bradley brothers and von Glasersfeld ended the day by climbing nearby Mount Clark and skiing the long way down as the sun set, filmed by Durrance.

The American team won the Australian championships—which were contested among Australia, America and New Zealand—because Durrance and Steve Bradley were four-event specialists. Annabel, in his article “Australian Championships, 1937,” provided closing thoughts about the meets. The international flavor of the Australian tournaments, he wrote, was shown by the presence of “two charming and capable members from the Ski Club Arlberg, Frau von Glasersfeld and her son, Ernst or ‘Bibu.’ Both these fluent runners were on all occasions a joy to watch with their correctly executed Arlberg technique. In the National Slalom, Ernst von Glasersfeld pressed Durrance very closely, and turned the tables by running the Townsend Course magnificently to win the Australian Downhill title.”

Skimeisters

The American team was especially impressive in its ability to succeed at the highest levels in the four-event competitions. According to Annabel, Durrance was the undisputed hero of the tournament, “a runner of extraordinary ability, and well worthy of the great name that had preceded him here.” Annabel continued,

To describe adequately Dick’s style is difficult under the usual standards, for this remarkable and highly unorthodox runner possesses a technique that seems to have been built up to suit his own particular physical attributes. It is an intriguing mixture of tempo schwung and land dive, while he maintains an unbelievable amount of vorlage throughout his running with what must surely be the world’s most powerful pair of legs. Crouching uncommonly low, he darts downhill and through slaloms at a great pace with the utmost nonchalance.

Durrance’s jumping, if not as efficiently executed, is as startling as his running. His jump of 40 metres in the championship on a “hill” that was deplorably flat and soft, was the result of super energy and perfect timing at the take-off; and, with superb steadiness on alighting, was an extraordinarily fine exhibition of aerodynamics. With langlaufing ability well up to standard, Durrance is the greatest all-around skier ever to race in Australia.

Steve Bradley’s alpine racing was impressive, but he will be remembered for his ski jumping and cross-country (langlauf). .... Steve Bradley’s performance at Charlotte’s Pass proved him a class slalom and downhill man. But it will be for his gloriously graceful jumping style that Steve Bradley will be most remembered in Australia. Using a fairly high stance he seemed to float, rather than jump, off the take-off, always getting well out with good vorlage, his body bent from the hips, landing with a delicate and attractive skidding without the semblance of a thud, and ever in complete control.

Dave Bradley, in spite of his injured hand, “got around surprisingly well and actually competed in the Australian Championship slalom with praiseworthy results,” reported Annabel. “It was indeed a tragedy that this visitor was physically unable to display fully his true skiing capabilities.”

Durrance recalled that the Australians were a bit wilder and tougher than the New Zealanders. The Americans, he wrote, made a “lot of university friends about our own age, plus the old-time pioneer skiers were there. . . . [We] did as much teaching as we did racing.” The trip broadened the Americans’ outlook on skiing before they returned to Dartmouth and Harvard for school.

The subsequent ski-industry careers of Durrance and the Bradley brothers are well known to regular Skiing History readers—they helped launch Alta, Aspen and Winter Park, and were all elected to the U.S. Ski Hall of Fame. Laughlin partnered with Durrance to become a key investor in Alta, then was a major force in American literature as founder and publisher of New Directions magazine. Von Glasersfeld became a world-famous mathematician and philosopher. He founded the Radical Constructivism movement in psychology.

John Lundin, an award-winning historian, is a regular contributor. Sources for this article include two articles in the American Ski Annual, 1937–1938: “Skiing in New Zealand,” by James Laughlin, and “South for Snow” by David J. Bradley; The Man on the Medal: The Life & Times of America’s First Great Ski Racer, by Dick Durrance, as told by John Jerome; and “Australian Championships, 1937,” by Walter B. Annabel, in the 1938 edition of The Australian and New Zealand Ski Year Book.