The “College” That Taught the South to Ski

How a Hollywood producer and a ski patroller brought big-time skiing to North Carolina.

The ski boom of the 1960s helped turn the high country of northwest North Carolina into a thriving tourist economy. In 1968, former governor (and future senator) Terry Sanford wanted to see for himself what was happening there, so he took an informal ski lesson at Beech Mountain from an acquaintance named Jack Lester. Lester was intrigued by Clif Taylor’s direct-to-parallel Graduated Length Method (GLM) and thus had put Sanford on short skis. They were spotted by ski school director Willi Falger, who promptly threw Lester off the mountain.

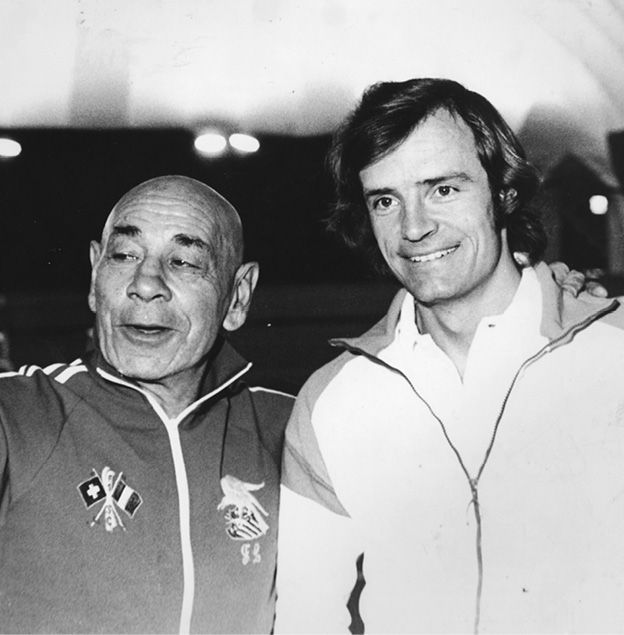

Photo top: Cottrell and Lester (center) with French-Swiss instructors displaying their American-flag sleeve patches. Courtesy Jim Cottrell Collection.

Falger, a native of Innsbruck, may have been incensed by the GLM challenge to Arlberg orthodoxy. Or maybe he was just chasing off an “underground” instructor. Either way, Lester went away with a chip on his shoulder.

Lester, a middle-aged U.S. Tennis Association referee and an accomplished player, was a charismatic and driven personality, with a flair for the dramatic. Built like a fireplug, he wore colorful dress and shaved his head. When in his 20s, the Atlanta native had worked as a producer, promoter and choreographer for stage acts, and then as a theater manager, eventually landing in Hollywood and, later, Australia. Lester claimed to have served as an officer in the Australian army. And he had the athletic skills and personality to coach tennis and skiing. But he didn’t look the part.

Meanwhile, Jim Cottrell, a native of nearby Boone, learned to ski in a unique phys-ed course at Appalachian State Teacher’s College, on the slopes of Blowing Rock Ski Lodge, a ski area. While earning a master’s degree in business from Appalachian State University, he joined the volunteer ski patrol and became its director. On graduating, Cottrell taught accounting at a community college in Charlotte and weekended at Blowing Rock. During the summer of 1969, Cottrell and Lester were neighbors in Charlotte and met at their apartment tennis courts. Tall, slim and movie-star handsome, Cottrell was an odd contrast to Lester, but they hit it off.

One of the things they had in common was a distaste for Arlberg-style ski instruction. Cottrell, for example, didn’t like the way the Austrian ski school staff took all the advanced classes and left beginners in the hands of less-experienced instructors; he had also become a fan of Georges Joubert’s coaching methods. Together, Lester and Cottrell cooked up the idea of an American-staffed ski school that would sell package lessons to groups like ski clubs, churches and colleges. For marketing purposes, they wanted to give the new school a European shine, but not an Austrian one. So they named their project the French-Swiss Ski College. Adding to the luster: the French and Swiss had won two-thirds of the medals in Alpine skiing at the 1968 Grenoble Olympics.

Blowing Rock Ski Lodge had recently been purchased outright by Grady Moretz, one of its original investors. Moretz renamed the place Appalachian Ski Mountain in 1968. Cottrell told Moretz about his group-booking concept and got the go-ahead to give it a try. He approached the community college phys-ed department and was told it would offer a skiing course if he recruited 10 students. “One hundred and twenty-three signed up,” Cottrell says.

In the winter of 1969–70, Lester and Cottrell launched their ski school on a card table in the lodge at Appalachian. They offered courses at seven North Carolina colleges. “The number grew to 43 the second year and within five years we’d developed more than one hundred college programs,” Cottrell recalls.

When the French-Swiss Ski College started, Appalachian Ski Mountain had a ski school, but as Cottrell found, “We eventually were booking more people than were walking in, so they decided they didn’t need [their own] school. Folks saw us and said, ‘We want to be in that group.’”

Lester had chutzpah. He pitched the Pentagon on providing ski lessons to the U.S. military. “The army wanted to cut the injury rate among servicemen learning [to ski] in Europe,” Cottrell recalls. In 1972, hundreds of Special Forces troops were diverted from winter training in Bavaria to North Carolina. Over two winters, platoons bivouacked in the ski area parking lot in big tents. “Each day started with a slog up the slopes with a 60-pound pack and an M-16,” Cottrell says. “They were running gates and racing before they left.” Cottrell and Lester taught more than a thousand Special Forces soldiers to ski. “Out of all those Green Berets,” Lester claimed, “there was one fracture, in a group that had never been on skis before.” Lester presented their commander, Brigadier General Henry E. “Gunfighter” Emerson, with a “Doctorate in Skiology.”

Photos from the time show French-Swiss instructors sporting “Airborne” arm patches gifted by troops. Ironically, the ski-trained soldiers shipped out not to mountain or Arctic stations, but to Vietnam. Ten of them later returned to become French-Swiss instructors themselves.

Early on, Cottrell says, he could never get North Carolina State University to work with French-Swiss. That changed when the new head of the university’s phys-ed department arrived from West Point. “He was interested when he saw we taught the Green Berets,” says Cottrell. Soon, Navy Seals, college ski clubs and thousands more followed. During the Ford administration, Cottrell recalls that French-Swiss trained Secret Service agents—though other sources say that some of the agents who skied with Ford at his Vail home had been expert skiers, even racers, before joining the force.

A Real French Star Arrives

One of Lester’s contacts was the First Union National Bank in Charlotte, where vice president C.C. Hope was marketing services to young executives. Skiing was a good match, and Hope organized a ski club for customers that would take lessons with French-Swiss. According to Cottrell, Lester took it a step further: Working with New York–based International Management Group (IMG) and its super-agent Mark McCormack, Lester encouraged the bank to underwrite a visit from Jean-Claude Killy, a Moët & Chandon spokesman, to promote the 1971 opening of Charlotte’s newest, tallest building, Jefferson First Union Tower (now Two Wells Fargo Center). “The company brought a truckload of champagne,” Cottrell says. “They had three fountains flowing with the stuff at the reception.”

Lester and Cottrell got to know Killy. A year later, for the premiere of Killy’s movie Snow Job, IMG and Warner Brothers brought the party to Boone. Killy, Cottrell and Lester—the latter resplendent in silk ski pants, fur boots and an eagle-embroidered sweater—were at the center of a major media event. Co-star (and Killy’s fiancée) Danièle Gaubert also attended, as did French ambassador Jacques Kosciusco-Morizet. Killy even taught a French-Swiss clinic for instructors from West Point. Two days later, the film screened in New York.

A year later, in 1973, Killy competed in a World Pro Skiing race at Beech Mountain. Characteristically, Lester told the local press that French-Swiss had arranged Killy’s “exclusive” visit. In truth, he was en route to the pro championship in his comeback year on the circuit and needed every race for the points.

Lester had become a regional rep for IMG and a personal manager of Jean-Claude Killy in the South. Killy was named an “honorary director” of the French-Swiss Ski College. Killy said privately that the ski school name was “grandiose,” but he made local guest appearances nonetheless. When rain cancelled ski training before the ’73 pro tour races, he got some tennis pointers from Lester at the resort’s tennis bubble. Killy also shared his pre-season ski-training exercises with Cottrell, who passed them along to college groups and wrote about them in a series of handbooks he published and revised over the decades.

Promotion Ramps Up

Always the showman, Lester took skiing to shopping malls with the French-Swiss Ski Revue, which performed on a 40-foot ramp. “Jack Lester’s motto was, ‘You gotta make ’em remember you,’” Cottrell recalls. “How could you go to a mall in the summer and not remember a man with shiny, skin-tight ski pants and furry boots with an eagle embroidered on his sweater?”

The program got its start during the summer of 1970 at the grand opening of the upscale South Park Mall in Charlotte. Over the course of a week, an estimated half-million people escaped the summer heat to watch the show in the air-conditioned mall. The ramp show then toured major Southern cities for a decade. “We got malls across the South to promote skiing,” Cottrell says. “No-cost marketing.” A French-Swiss ski village at the base of the ramp showcased ski clubs, ski shops and travel agents.

Presidential Recognition

In early 1974, French-Swiss affiliated with the President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports. Lester was named the national program’s director of skiing, and Cottrell developed the ski program. At Appalachian Ski Mountain, French-Swiss awarded more of the program’s patches for Alpine skiing than did any other resort in the country.

Lester wanted to franchise the French-Swiss Ski College nationally and internationally, but never got the chance. In summer 1974 he had open-heart surgery, and a massive heart attack later killed him at age 65. Cottrell carried on.

Joining the Special Olympics

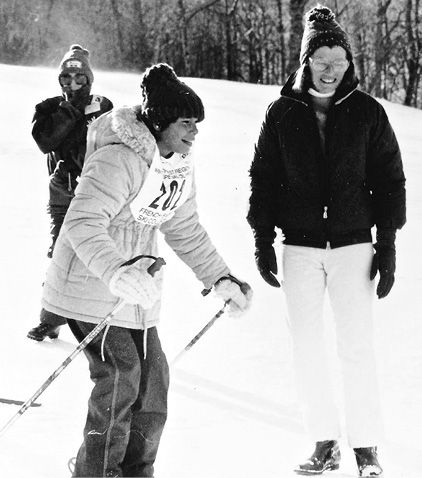

One of the most important contributions French-Swiss made to skiing was through its role in the Special Olympics. In 1976, Cottrell met the director of Special Olympics North Carolina, Monty Castevens, who told him that a group of his athletes would attend the first International Special Olympics Winter Games at Steamboat Springs, Colorado, in 1977. When he asked who was training the athletes, Cottrell was told they weren’t being trained. “I didn’t think we should send never-evers,” he says. “The South already had too much of a ‘skiing on grits’ image.”

Thus, Cottrell put together a three-day pre-games training program at Appalachian. When Castevens got back, Cottrell proposed starting an annual regional games “so we’d have trained athletes for the next international games.” The 1978 Southeast U.S. Winter Games—the first regional Special Olympics winter games in the country—“was a disaster,” Cottrell says. “Everything we took for granted didn’t work. And with cognitive disabilities, the athletes couldn’t communicate the solution.”

He continues, “It took hours to get people outfitted and when they came in for lunch, just one person getting the wrong skis started a chain reaction that took hours to sort out. At the end of that year, we said, ‘How do we fix this?’”

Ultimately, the process became tightly organized. “Everybody had a bib with a number,” Cottrell explains, “so we put a bib number on their skis and matched them up in an instant. Eventually, every piece of equipment had the bib number and the athlete’s first name—huge name on the bib, front and back, so volunteers could always shout encouragement, coming and going.” The ’79 Games were vastly improved. Even with 300 special athletes, skis, boots, poles and helmets were easily accessed, used and returned.

By the 1980 games, Special Olympics founder Eunice Kennedy Shriver “had heard what we were doing and came down to observe,” says Cottrell, who had by then completed a coaches’ manual and the first operations manual for organizers. Shriver followed up by asking Cottrell to attend the 1980 Directors’ Conference, an international gathering to plan the 1981 International Special Olympics Winter Games in Smugglers Notch, Vermont. The meeting was also the first national training school for Special Olympics program coordinators, with a theme of “Training for the Future.” Cottrell wowed attendees with creative, time-tested processes for organization and surprisingly effective instructional techniques for the intellectually challenged.

Later, Shriver invited Cottrell to move to Washington and head the Special Olympics winter sports program, but he demurred. “I didn’t want to leave God’s country,” he says. But he began volunteering 30 days a year to train instructors, coaches and games directors, visiting many states and Canada.

Every year since 1978—46 times—Appalachian Ski Mountain has hosted the regional winter games. French-Swiss methods ultimately became the program’s template nationwide and are still in use. Over time, Cottrell discovered that teaching any kind of new skiers how to get in and out of gear, how to get up from a fall and other basics was easier done indoors. “First-timers get hit with a lot at once, even if they’re doctors or lawyers,” he says. “Thanks to Special Olympics, we found out how to eliminate some of the trauma before we ever stepped on snow. Had we not been doing Special Olympics, we never might have learned all that.”

A Lasting Legacy

Cottrell’s independent ski school at Appalachian eventually merged with the Professional Ski Instructors of America and its evolving American-oriented methodology. Cottrell became a PSIA Level III–certified ski instructor, and in 2019, on the 50th anniversary of French-Swiss, he was honored with PSIA Eastern Division’s Regional Recognition Award.

French-Swiss recorded its one millionth lesson in 2005. By then, snowboarding was part of the curriculum. Today, Appalachian has three terrain parks and a Burton Learn-to-Ride Center plus a famous alum: Luke Winkelmann, who is now on the U.S. Snowboard Team. Cottrell, meanwhile, retired in 2022 and the resort bought the ski school, which is now run by French-Swiss veteran Benjamin Marcellin—an actual Frenchman.

Cottrell still skis every day of the winter, at his home slope and elsewhere. He closed out an 89-day ski season last spring at Montana’s Big Sky resort. After that, per tradition, he spent a few weeks in Aruba, building on 40 years as a certified wind-surfing instructor. “I wanted to set up a wind-surfing program somewhere during the summer,” he confesses, “but my wife, Wynne, said no. She told me, ‘I am a ski widow all winter—we’re not doing that in the summer.’”

Each year, after Appalachian’s Meltdown Games event in March, Cottrell ends the season in the parking lot with a gathering of instructors from the 1980s and their children and grandchildren. “We’ve come from virtually no skiers in this region to generations now,” he says. That achievement reflects the essence of the French-Swiss method, which Cottrell describes as “a teaching style based on what we learned from the Special Olympics: that people learn at very different rates and that patience and a caring attitude are essential parts of a skier’s success.”

Sounds like the perfect approach for a region where most people never or rarely see snow. No wonder the accents of Southern skiers are now heard all over the country and around the world.

Randy Johnson’s book Southern Snow: The New Guide to Winter Sports from Maryland to the Southern Appalachians includes a deep dive into Southern ski history. He wrote “Pioneers of Southland Skiing” in the July-August 2022 issue.