Stephanie Sloan

The first World Cup freestyle overall champion became a Whistler realtor, arts maven and town official.

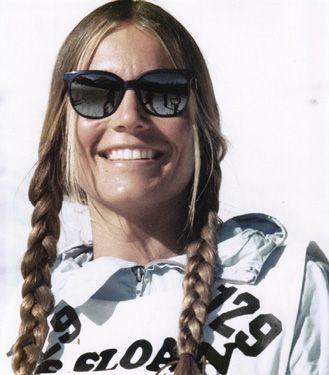

Photo top: Stephanie Sloan graces a 1985 bus billboard. All photos courtesy Stephanie Sloan.

She was there. A floss-haired hippie with mirrored specs and, yes, a flower in her hair. Canadian freestyle skier Stephanie Sloan was a fixture at burner parties in the ’70s outside Whistler’s Toad Hall in British Columbia. She witnessed the gestation of hot-dog skiing and the lifestyle of the freestyle circuit alongside Suzy Chaffee and John Eaves. She fan-girled the Crazy Canucks in Tignes and Val d’Isère in 1975, watching them beat the Austrians by being, uh, crazy. She toured Europe, Scandinavia and North America on the freestyle World Cup as one of the few women who could outski the guys.

She came back to Whistler in the early 1980s, just as Blackcomb was reborn as a seventh heaven and at the exact moment summer ski camps became the hip new thing on the glacier. She married the ski racer every other Canadian skier girl wanted to marry, Dave Murray. And then—and then—Sloan joined the Whistler town council to help guide the ski village through its growth spurt and bring the Olympics to town. Now 72, this woman has stories to tell.

Sloan grew up near Toronto and in Calgary, where she learned to race in the mid-1950s and ’60s. Her grandfather, John Turner, was a gallery owner and artist heavily influenced by Canada’s Group of Seven. Her mother, Joyce Turner, followed his artistic path. But when Joyce remarried while Sloan was in her early teens, the family headed back to Toronto, with skiing available in Collingwood, Ontario, at Osler Bluff Ski Club. “Ski racing in the late ’60s saved me,” Sloan says. “It gave me community—we skied and traveled a ton. But it all ended fast. I was headed for the Kokanee Glacier to summer train at age 17 when I broke my ankle. It didn’t heal very well. That was the end of the line for me.”

Instead, Sloan set out for Ottawa’s Carleton University, hoping to study journalism—a plan that didn’t last long. A spring-break ski trip introduced her to the place over which she’d eventually have so much influence: Whistler. With freshman year finished, Sloan checked out of Carleton and moved to a hippie camp near Whistler’s base. “Those were the Soo Valley days,” she says.

Soo Valley is notorious. It was to Whistler what Haight-Ashbury was to San Franciso. Say Soo Valley to a true Whistlerite, and they’ll know exactly what you mean. “With a mere $75/month lease (for the property, not per person),” states WhistlerMuseum.org, “this collection of wooden shacks near the north end of Green Lake, formerly known as the Soo Valley Logging Camp, came to be a focal point of the rebellious ski-bum community. Without going into too much detail, let’s just say that by the spring of 1973 tales of debauchery left local powers wholly unenthused with this shag-carpeted Shangri-la.”

“We were all ski bums,” Sloan says mildly. “It was pretty epic. We’d have these outrageous parties—huge burners where we’d burn scrap in a big fire in the middle of a field.” Someone hired a helicopter once to lift the ski bums up to Wedge Mountain. Sloan was the only woman among 20 guys—“one of the reasons I liked it so much,” she admits now.

At one point, Toad Hall, a rustic cabin acting as the encampment’s base, was marked for demolition. “One sunny spring day,” states the museum’s website, “whoever was milling about was asked to convene out front with their ski gear but wearing nothing else. The photographer, Chris Speedie, orchestrated the photo simply to provide residents with a memento before Toad Hall met its demise.” But the Toad Hall naked skier poster blew up. It’s now a vintage ski memorabilia collector’s major score—there’s one in Kitzbühel’s Londoner Bar with the inscription “Canada’s National Ski Team.” “Yeah,” says Sloan, “I was there the day Speedie took the photograph. Everyone thinks I’m the woman doing the [naked] handstand, but I’m not. I’m so glad I didn’t do that. I was there but that wasn’t me.”

The next winter Sloan headed for France, hoping to earn cash by picking wine grapes. Instead, she got sidetracked, ending up in Geneva working as an au pair. But a spring-break trip to Chamonix compelled her to reconsider nanny life. “I came back and said to the family: ‘Sorry, I gotta go!’”

After a whole winter in Chamonix, in the spring of 1975 Sloan watched a Europa Cup moguls event in which only one woman competed against the men. “Oh, I can do that,” she said to herself at the time. Sloan and her Swedish boyfriend began crisscrossing Europe and Scandinavia, working odd jobs, partying and competing in freestyle events. “Everything was just beginning,” she says. “Ski sponsors were all over [this] brand-new sport. I got sponsored easily, and the money was good.” By the summer of ’76 Sloan was sleeping on a friend’s floor somewhere in Sweden to train on a jump with a water landing in the Baltic Sea. “We trained every moment we could, learning how to flip,” she says.

Sloan remembers those early days of freestyle as a time when “everyone did everything, all disciplines [moguls, aerials, ballet]. We did flips and Wong Banger turns in the bumps, mixing it all up.” Big names on the circuit included Greg Athans and Penelope Street. “Wayne Wong was on his way out at the time,” says Sloan, “but the Bowie brothers were big competitors.” Doing all three events, with a specialty in bumps, Sloan competed on the pro freestyle tour beginning in 1976, winning world championships in 1978 and ’79. In 1980, the first year of FIS World Cup freestyle, she won the overall and combined championships. In 1981 she finished third overall, and retired.

In December 1975 Sloan paused long enough to watch the Crazy Canucks race downhill at Val d’Isère, a race Ken Read won. “I partied with the team after Ken’s win,” she says. Crazy Canucks team members included Read, Steve Podborski, Dave Irwin and Dave Murray. She hit it off with Murray.

Both busy with World Cup circuits, it took until 1981 for Murray and Sloan to retire from competition and get together. By then Sloan was earning money as a ski-action model. The two traveled to Maui to windsurf each summer, and in winter they skied Whistler. Murray became director of skiing at Whistler Mountain, while Sloan coached women’s ski and bump camps on Blackcomb. By 1983 she was heading the Stephanie Sloan Women Only ski programs, and the two took over operations for the Nancy Greene/Toni Sailer–run summer racing and freestyle camps on the Whistler glacier.

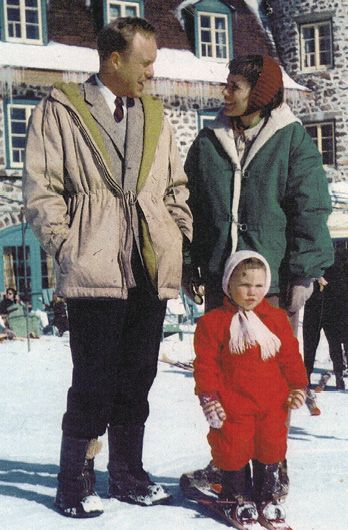

Murray’s malignant melanoma diagnosis in 1985 was a serious blow. But, says Sloan, “we thought we could beat it.” They married in 1987, and their daughter, Julia, was born in 1988. Twenty-two months later, with a toddler and a busy ski business, Murray lost his battle with cancer.

“I don’t know how I got through it,” Sloan says now. “I just put one foot in front of the other. David would not want me to wallow. He wanted me to live my life. Julia was a focus; she was an amazing kid—happy and wonderful. I focused on her and being the best mom I could.” The Dave Murray Ski and Snowboard Camps continued to thrive. She moved them from Whistler to Blackcomb in 1991 and ran them until 2000, then sold the business.

Next came small-town politics. Sloan joined the Whistler Arts Council in 1994 and founded Whistler’s Public Art Committee in ’96, then served two terms as a town councilor. From 1996 to 2002 Sloan helped Whistler win the 2010 Olympic bid and assisted in the creation of Millennium Place and the Squamish Lil’wat Cultural Centre. Supporting the family financially as a Realtor, Sloan put her daughter into ski racing and—surprise!—she excelled: Whistler’s Julia Murray competed for five years on the Canadian National Ski Cross Team; she was an Olympian at the Whistler Games in 2010.

Since her recent retirement from real estate, Sloan has kept her hand in sport, now serving as a board member for the Canadian Sport Institute Pacific, which runs facilities in British Columbia that offer training for elite athletes and coaches. But what she’s really passionate about these days is wing foiling, a mix of kite- and windsurfing. With her husband, Realtor Ray Longmuir, she goes to Maui each November. “Because that’s where the waves are breaking,” she says. We’d expect nothing less from a three-time world freeskiing champion who really was there.

Lori Knowles is co-editor of Ski Canada magazine.