Sunshine on My Shoulders: A History of Ski Music and Song

Photo: Robert Doisneau: Maurice Baquet a Chamonix, 1957/Getty Images

Click here to read the full article and listen to the tunes!

Skiers used to yodel and sing about the sport.

Two boards upon cold, powder snow, yo-ho, what else does a man need to know? goes the refrain of the Tirolean ballad Der Feinste Sport (The Finest Sport).

As a professor of entertainment law at New York University, I’ve taught courses on the relationship of music to history. I’ve also been skiing, all over the world, for some 50 years. It finally occurred to me that while music and skiing have been culturally intertwined for hundreds of years, and ski songs are woven deeply into the fabric of the sport, little has been written about how and why that incredible melding of art and athletics came to be. That, I concluded, is what else a skier needs to know.

The result is a series of online feature articles entitled Sunshine on My Shoulders, crafted specially for members of the International Skiing History Association for their reading and listening pleasure. Links to 200 musical examples illustrate how skiing and music developed side by side from the 19th to the 21st centuries, mirroring momentous times in history.

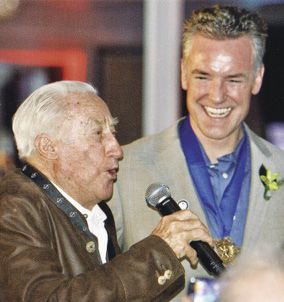

This project was inspired by conversations with yodeling superstar Klaus Obermeyer at the 2017 Skiing History Week in Aspen. Sunshine traces the long trail of ski song, from Romantic Age composers and Alpine singing groups of the belle epoque, to the musical influence of the Italian mountain soldiers of World War I, and the eventual collapse of the joyous ski heil singing tradition of the German-speaking Alps into a militarized celebration of hate in the 1930s and ’40s.

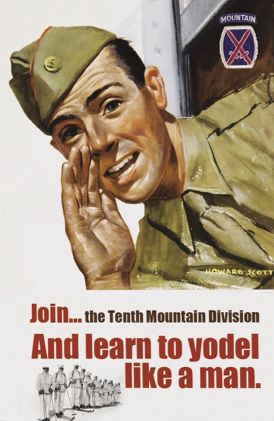

Of course, it’s not all serious. We cover the hilarious song-parody traditions developed in North America by the Carcajou Ski Club at Dartmouth, the Red Birds of Quebec and, especially, the U.S. 10th Mountain Division. There are stories of Glenn Miller and his “Sun Valley Serenade,” “Ninety Pounds of Rucksack” and “Happy Wanderers”; the great Jo Stafford’s recording of “Moonlight in Vermont”; and the impeccable contributions of John Denver.

The postwar ski boom and folk music explosion, led by singers like Bob Gibson and Ray Conrad, serve as the prelude to music in ski films, from the works of Roger Brown, Dick Barrymore and Greg Stump to mainstream movies such as the Beatles’ Help! and Robert Redford’s Downhill Racer. From Hansi Hinterseer’s Ski Twist franchise to the rebirth of the après-ski sing-along tradition on steroids at the Krazy Kangahruh in St. Anton, it’s all covered. Did we miss something? Add your own musical memories in the comments section.

American lyrical genius Yip Harburg (“Over the Rainbow”) perhaps explained the phenomenon best: “Words make you think a thought. Music makes you feel a feeling. A song makes you feel a thought.” Klaus Obermeyer knows exactly what Harburg was getting at. “Skiing,” he insists after a century on snow, “is just the realization of the ecstasy music strives to inspire.”

understands the link between music

and mountains. "Skiing is just the

realization of the ecstasy music strives

to inspire," he says.

It began with yodeling

Aspen’s beloved centenarian, the world-class yodeler and ski apparel legend Klaus Obermeyer, has a theory why skiing and music will always be inextricably linked. “To express feelings as happy as sliding down a mountain through powder snow and sunshine,” he philosophizes through his million-watt smile, “they must be sung. Words alone can’t convey that much joy.”

“Yodeling,” Obermeyer insists, “was the beginning. Absolutely. When skiing became popular, those yodeling tunes were turned into songs about the happiness you feel when you reach the summit and go flying down. Sometimes you yodel out loud, sometimes inside. But we all sing in our own way. That’s the basis of all ski music. It’s yodeling for the pure joy of playing in the snow.”

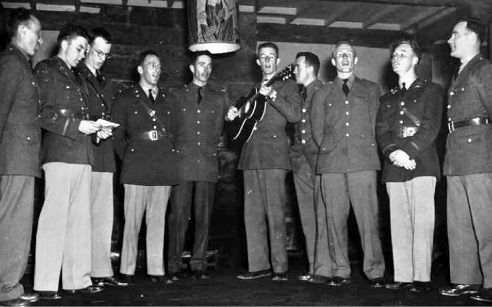

Mountain troops in World War I

enjoyed camaraderie in the early days

of World War I -- until Italy declared war

on Austria.

World War I came to the Alps in 1914. The Austrian ski-technique pioneer and “father of modern skiing” Hannes Schneider served as a trainer of his nation’s ski troops on the Sud Tirolean front. Many of the men about to face one another in combat had grown up climbing, skiing and singing together in those same mountains. Going into battle against each other would literally pit friend against friend, an eventuality they sought to avoid for as long as possible.

As a result, even after the First World War began in earnest that autumn, the ski heil spirit of camaraderie among mountain troops persisted. That was especially true after Italy declared its neutrality in the struggle between the Western Allies and Russia on one side and Germany, Austria-Hungary and Turkey on the other. Austrian and Italian ski troops on either end of the Dolomite border continued to chat bilingually, trade food and bottles of wine, and drink and sing together. Maintaining a code of fellowship in wartime, however, was simply not possible after Italy joined the Allies in April 1915, and declared war on Austria. That reality was later starkly depicted in German actor-director Luis Trenker’s 1931 mountain film Berge in Flammen (Mountain on Fire), which featured military singing as part of its grueling and dramatic war reenactments.

Hampshire, February 1939. Left to right:

Herbert, Hannes and Ludwina Schneider

with Harvey Dow Gibson. New England

Ski Museum

Austrians in America

[In North Conway, Harvey] Gibson even honored [Hannes] Schneider with a measure of musical revenge against his former captors. When a German diplomat visited the Eastern Slope Inn in 1939, the proprietor told his hotel’s bandleader that he was to play at dinner only music written by “non-Aryan” composers. After a night showcasing the works of George Gershwin, Irving Berlin, Yip Harburg and the expelled German composer and lyricist Kurt Weil (most famous for “Mack the Knife”), the Nazi statesman and his entourage understood the insult and stomped out of the dining room. According to Hannes’ son Herbert, the Schneider family was elated over Gibson’s gesture.

North American drinking songs

Prior to the 1939 arrival in New Hampshire of Hannes Schneider’s ski school in exile, the catalog of American and Canadian ski tunes was limited nearly exclusively to humorous, and sometimes risqué, parodies of popular songs, lyrically transfigured by the members of local college ski teams and winter outing clubs to promote bonding among their members. Here and there were smatterings of German language mountain lyrics and melodies carried home by those few who had skied in Europe, but even those compositions were frequently, tipsily translated into American-ese for local consumption.

The Carcajou Ski Club—founded by veterans of the national champion Dartmouth College Ski Teams and local skiers of Hanover, New Hampshire—was a prime example. The members no doubt did ski together, but the real point of the club, according to the lyrics of its favorite ski songs, was gathering on cold New England evenings to sing parodies until the beer and wine ran out. Even Dartmouth’s most sacred, fraternal hymn, the “Hanover Winter Song,” falls hard into the “drinks by the fire” category of both Ivy League and hardscrabble Northeastern fellowship.

Soon to become the 10th Mountain

Division Chorus. US Army.

Ninety Pounds of Rucksack

By far the most enduring tune written for the 10th Mountain Division is its ubiquitous anthem, “Ninety Pounds of Rucksack” (sung to the tune of “Bell Bottom Trousers”). Oddly, however, it is the one 10th Mountain Division song whose provenance is most difficult to trace. Charles McLane was certain that he and Ralph Bromaghin had a strong hand in creating the parody lyrics. Other sources, including The Skier’s Songbook (a revered collection compiled by David Kemp, published in 1950), list the song as “Never Trust a Skier an Inch Above the Knee,” credited to 10th Mountaineers Billy Neidner, Dick Johnson and Don Hawkins. Regardless of

by Howard Scott, intended for a

USO fundraiser.

its various sources and titles, no history of American ski music is complete without devout reference to it, if for no other reason than its unique, life-long popularity among those who came home from war, founded the North American ski industry, and invented a good deal of the post-war skiing culture that it sparked.

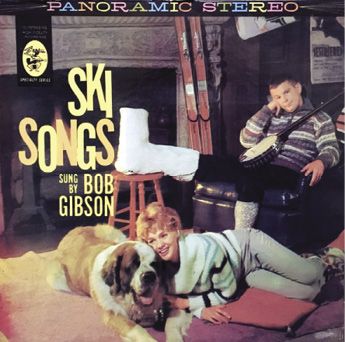

Bob Gibson and the folksong revival

released this album in 1959.

It was the commencement of a U.S. folk music boom in the late 1950s, coinciding with the explosion in popularity of North American skiing, that created the opportunity for the first real star of American ski music to emerge. His name was Samuel Robert “Bob” Gibson, a Pete Seeger acolyte from Brooklyn who possessed genuine street cred as a leader of the new American folk movement. Gibson’s career included a stint in Aspen, where he fell madly in love with skiing. Leading a double life by commuting between Ajax Mountain and the folk circuit, Gibson managed to become a creditable Colorado downhiller. Meanwhile, he discover and introduce Joan Baez to the world at the 1959 Newport Folk Festival, and become instrumental in getting Judy Collins to sign with him to Jac Holzman’s up-and-coming Elektra Records. He also found time in 1959 to co-write and record the album Ski Songs, containing both original and classic skiing-based compositions mainly performed in the 1930s New England frat-style. The selections were so humorously impressive that (along with his socially conscious “straight” folk performances), they influenced an entire generation of future singer-songwriters. His fans and disciples stretched from The Byrds and Paul Simon (who covered his non-skiing songs) to Collins, Harry Chapin, John Denver and James Taylor. According to Peter Yarrow of Peter Paul & Mary, the New York folk icon who has spent most of his post-folk era life skiing in Telluride, Colorado, “when you listened to us, you were hearing Bob Gibson.”

John Denver’s mountain spirituality

John Denver, who was born in Roswell, New Mexico in 1943, had by the mid-1970s become the living, international symbol of American Rocky Mountain skiing. His top-rated “Rocky Mountain Christmas” TV specials were by then annually drawing audiences of over 60 million viewers to watch him sing and ski, adding yet another dimension of success to both his career and the sport.

By the early 1980s, over thirty of Denver’s songs and albums had already gone gold or platinum around the world. Those hits included skiing and Alpine favorites like “Starwood in Aspen,” the Gibson-esque ecology masterpiece “Eagle and the Hawk,” “Dancing with the Mountain,” “Annie’s Song,” “Song of Wyoming,” “Wild Montana Skies,” “Alaska and Me,” The Gold and Beyond” (which served as the theme of the 1984 Sarajevo Winter Olympics), and the extraordinary ballad “Sunshine on My Shoulders,” (written with Mike Taylor and folk bassist Dick Kniss), which featured what many consider the perfect expression of spiritual generosity that defines the skiing and mountain lifestyles.

Suddenly, in bars lining the roads to every ski area in North America, skiers were mouthing the lyrics to John Denver songs played by guitarists on tiny stages urging the crowd to sing out louder. It wasn’t quite the same as the [fireside singing of the] old days, but it was a reasonable facsimile. Ski music sing-alongs in the traditional sense hadn’t returned, but the spirit of celebrating a great day on the slopes with a beer, friends and a sentimental song of the mountains was certainly reborn.

Charlie Sanders is a director of ISHA and the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame and serves on the advisory board of Protect Our Winters. He is author of the award-winning book Boys of Winter: Life and Death in the U.S. Ski Troops During the Second World War, and of “Skiing the Seven Continents” (Skiing History supplement, 2020).