Technique: Whatever Happened to Lead Change?

In the beginning, we pushed the outside ski forward. Then what?

In skiing, traversing across the hill means that the uphill leg needs to be shorter than the downhill leg. This means the uphill knee and hip are naturally bent more than the downhill knee and hip, which pushes the uphill ski slightly forward. We say that the uphill ski leads, and as we complete a turn, changing edges and shifting weight, we also change the lead.

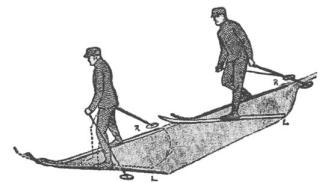

Drawing top of page: Vivian Caulfeild explained the stem turn as a half-hearted Telemark in 1912.

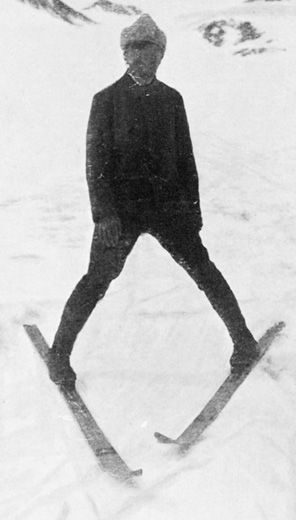

One mark of an intermediate skier is too much lead with the uphill ski, a situation ski instructors call scissoring. This position tends to put the skier too far forward on the weighted downhill ski—allowing the tail to skid—and too far back on the unweighted uphill ski, delaying the actions needed to start a new turn.

Thus one of the skills learned en route to expert skiing, especially on ice, is reducing lead, which is done by consciously pushing the outside (or downhill) foot forward as the turn develops. This helps keep the skier’s weight centered on the newly weighted downhill ski, making efficient use of the entire inside edge in gripping hard snow.

It’s not a new idea. When the first instructional books were written in the early 20th century, skis had no steel edges, and leather boots lifted at the heel for climbing and walking. Alpine skis were simply wider cross-country skis. Because the boot was low, soft and only loosely attached to the ski, no leverage was available to steer a ski in deep snow. The only turn that worked well in deep snow, therefore, was the telemark. Beginners were advised to telemark in powder and “skid-turn” or “stem-turn” or Christie on firm surfaces. The telemark turn, of course, is accomplished with a dramatic lead of the outside ski, accompanied by edging and steering it across the path of the trailing, unweighted inside ski.

Early writers on Alpine technique, like the mountaineer Willi Rickmer Rickmers (Ski-ing for Beginners and Mountaineers, 1910) and Vivian Caulfeild (How to Ski (And How Not To), 1912, and Skiing Turns, 1922) said little about lead change in stem-turn skiing, but the photos they used to illustrate their books usually showed a slight lead of the outside ski, like a subtle remembrance of the telemark. Of the snowplow, Rickmers advised, “If one is running right foot in front, one shifts [stems] the right ski, places the weight of the body on it and comes round to the left.”

Matters changed after 1928, when Alpine racers adopted the Amstutz spring and the Kandahar cable binding to hold down the boot heel for better ski control. They were now able to steer with better assurance and, helped by the also-new steel ski edges, to edge with as much power and accuracy as low boots would provide. A transitional decade followed, in which springy heel cables and leather boot soles permitted an inch or two of heel lift. With heels locked down, however, it took more muscle to push the downhill ski forward, and many Alpine racers fell into a scissoring habit.

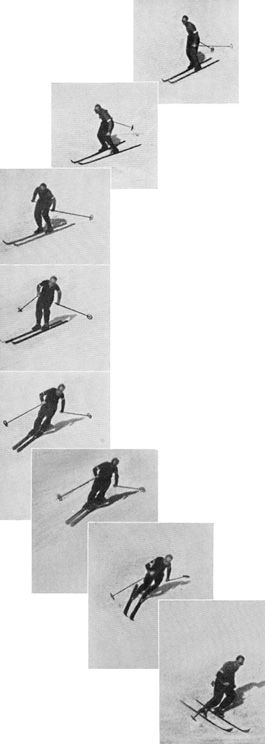

But the fastest skiers minimized lead change. Toni Seelos of Seefeld locked his heels down solidly and invented the parallel turn; by learning to use the

entire length of the steel edge, he limited the amount he allowed the inside, or uphill, ski to lead. Dick Durrance then brought that technique to

North America. By 1938, Benno Rybizka, writing on behalf of the Hannes Schneider Ski School (The Hannes Schneider Ski Technique, 1938) never demonstrated a stem without pushing the outside ski ahead. And Dartmouth Coach Walter Prager (Skiing, 1939) advised little or no lead change, or a little outside lead with the stem.

As late as the 1960s, Sir Arnold Lunn advised his friends that the secret to effortless turns was to lead with the outside, weighted ski. But the era of higher, stiffer boots locked the ankle in a strong, safe vorlage position, which had the effect of

pushing the uphill ski forward. To most skiers, it felt natural to allow the lead to change as the skis passed through the fall line. In fact, this effect was encouraged at the time. In Ultimate Skiing (2010), Ron LeMaster wrote, “Back in the 1950s and 1960s, skiers were often taught to deliberately shove the inside ski ahead . . . when starting a turn, and many thought that the lead change a good skier made going from one turn to the next was a fundamental movement of good turns.” Only stronger skiers learned to hold the tips even so as to use the power of the entire outside ski.

Today, coaches and technicians spend a lot of time demonstrating how to load the boot heel without relieving pressure between the shin and boot tongue. The best way to do this? By advancing the outside ski and keeping the tips even.