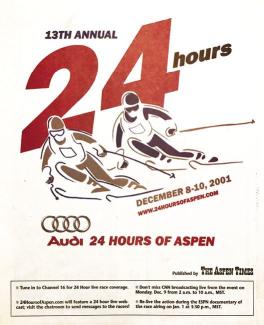

Short Turns: 24 Hours of Aspen

A brutal race format from the past now seems improbable in the future.

Not many skiers have ever gone 90 to 100 miles an hour down Aspen Mountain. But of the few who have, most did it up to 80-plus times in a day, once a year. And it wasn’t in the annual FIS and World Cup downhill races that have spanned the last eight decades. It happened in the now-defunct 24 Hours of Aspen events, which were held from 1988 through 2002, where skiers on a course with virtually no gates regularly flirted with the 100-mile-an-hour mark. And they did it on every single run, all day and all night, non-stop and bumper-to-bumper with a teammate.

“Skiing so close together at high speed is amazingly dangerous,” British Olympian Martin Bell told Sports Illustrated in 1996. “Which way will I go when he crashes? It’s nerve-wracking. And when it gets dark and you can’t see as well, the danger is doubled.”

The rules of the charity endurance event were brutal in their simplicity: Two-person teams must ski together down Aspen’s Spar Gulch downhill course as many times as possible in a 24-hour span. The duo can rest only during the 14-minute gondola ride back to the top. The team completing the most runs wins. That’s it.

Indeed. Imagine tearing across the upper-mountain rollers under eerie lights at 4:00 a.m., on 225-cm downhill skis in a full tuck and a speed-suit 18 hours into the event. Delirium was a frequent companion late in a 24-hour race whose average pace was well beyond the speed limit in most states. “The constant roar of wind starts to get to you,” Ian McLendon said in a 2001 Aspen Times story. “And the whipping of your ski suit. It’s like the wind is trying to pry it off your body.”

Competitor Matt Ross described the night skiing as “really eerie” and “pretty trippy.” And Chris Davenport, longtime local resident and 1998 winner with Tyler Williams, said, “Words don’t really do the mental state justice.”

The stories of the physical and psychological traumas (frostbite, mega-blisters, severe cramps, hallucinations, paranoia, vomiting, bad wrecks and so on), are legion. The tales sound like a snowbound Death Race movie without the cars. But for some adrenaline-addicted racers, the event was the high point of the winter.

The 24-hour endurance race was a kind of hybrid speed-skiing/Ironman-team ski-a-thon dreamed up by local snowcat operator and itinerant ski racer Ed McCaffrey. Thinking of his father’s battle with multiple sclerosis, he conceived of it as a unique challenge that might be entertaining enough to be a lucrative annual MS fundraiser.

It took a couple of years to find a sponsor, in addition to a location willing to host the oddball event. The first race was in December 1987 at Keystone, Colorado. Five teams participated, and McCaffrey and his partner won, setting a record for vertical in a day and raising $10,000 for the Jimmie Heuga Center in Vail.

The race caused such a stir that the next year it attracted eight international teams and media attention from around the world. It also moved permanently to Aspen, where the bottom-to-top gondola was the perfect facilitator, serving a 2.69-mile track that dropped 3,267 vertical feet. The 24-hour numbers are numbing: Winners typically skied more than 80 laps and racked up 270,000 vertical feet. That would be on the order of 222 miles; average speed on the snow was about 63 miles per hour.

Attempting to explain the event’s unexpected popularity with competitors, given there was no prize money, the 38-year-old McCaffrey said, “You push yourself so far out there that you reach this trance-like state of blissful exhaustion. It’s truly amazing, It keeps people coming back every year.”

With title sponsors Audi and the Aspen Skiing Company, the event rapidly evolved into a high-maintenance production unlike any other race in the world. Support was not only required across a broad front, but for 24 hours straight. The 800 volunteers included physicians, ski patrol, ski techs, massage therapists, food handlers, lifties, lighting and course crews and on and on, many of whom pulled all-nighters.

On a course with a long, flat start and little emphasis on turning, elite ski techs were vital for teams that hoped to be competitive and consisted of local savants like Bill Miller, Jeff Hamilton and Dave Stapleton and pros from the World Cup and speed-skiing tours. Hamilton told the Aspen Times that the 24-hour race format presents challenges for the techs not seen on the World Cup circuit: “What we need to be able to do is change and adapt. It’s not a one-lap race.”

A further distinction from other ski races was that the competitors spent most of their time (about 20 hours) on the lift. So the gondola became another major focal point and served as a racer’s micro apartment—for 14 minutes. Racers ate and drank, rested their legs and got massages; tried to warm up or cool down using special comforters designed to help flush lactic acid from their muscles; sank into fitful naps (often with hallucinations); changed clothes and boots and relieved themselves into Ziploc baggies and buckets of kitty litter.

In the end, despite all its crazed uniqueness and media attention, the event couldn’t survive. It was turned into a solo race with a cash award in 2002 in the hope of attracting bigger names and bigger sponsors. Tyler Williams, winner in 1998 with Chris Davenport, says the race lost its mojo when it changed to an individual competition. “I think it was more exciting for the fans when there were teams,” he said.

Then again, maybe the ski world had simply moved on. The last 24 Hours of Aspen in 2002 was the same year that the Aspen Skiing Company decided to put its resources

behind hosting a new oddball winter event. The X Games.

Snapshots in Time

Snapshots in Time

1936 PRE-SEASON BUSTLE

The phenomenal development of skiing last year, unprecedented in the annals of sportdom, will be completely overshadowed this Winter if pre-season bustle can serve as a barometer. The department and sporting goods stores, profiting from last year’s experience when they were caught unawares by the “boom,” are already displaying in their show windows the newest modes of skiing equipment and apparel. The stores have also constructed indoor slides on carpets of borax in an Alpine setting, thus giving the more enthusiastic skier a chance to brush up on his technique. — Frank Elkins, “Ski Stage Being Set” (New York Times, November 22, 1936)

1969 KILLY'S BLUNDER

Until now, skiing has represented to me the last avenue of escape from the chaos of an undisciplined society. In skiing, we have been fortunate in having great sportsmen like Stein Eriksen to follow in the search for perfect form. To deprecate technique or the work done by the Professional Ski Instructors of America is no more than an attempt at embracing creative expression as an excuse for technical inadequacy. Even more dangerous are articles by J.C. Killy which might as well be titled, “I can’t keep my skis together, so don’t worry if you have the same problem.” This champion is actually trying to convince our sport that form is unnecessary. — Frank Covino,

Sugarbush Ski School, Vermont, “Form is a Must” (Letters, Skiing Magazine, September 1969)

1990 FOR SALE: U.S. SKI TEAM

Designer labels may go out of style in the 1990s, as many pundits predict, but logos are definitely in for members of the U.S. Ski Team, who will be sporting up to four different manufacturers’ logos this coming season. The International Ski Federation (FIS), which governs such matters, has doubled its billboard space limit to four logos. That’s not enough to get our skiers confused with Indy race cars (or skiers on the U.S. Pro Tour), but it is another step in the growing commercialization of World Cup ski racing. Whatever the on-course fortunes of the USST, it's a gold medalist as a fundraising organization.— Rick Kahl, “U.S. Billboard Team” (Skiing Magazine, October 1990)

2011 YUP

“Skiers make the best lovers because they don’t sit in front of a television like couch potatoes. They take a risk and they wiggle their behinds. They also meet new people on the ski lift.” — Cal Fussman, “Ruth Westheimer: What I’ve Learned” (Esquire, January 2011)

2016 THE GREEN MONSTER AND BIG AIR

Fenway Park has been the home of the Boston Red Sox since 1912. While baseball is the main focus of the stadium, it has hosted other events such as concerts, football, soccer and even hockey. Now the 104-year-old stadium can add a couple other winter sports to its resume: skiing and snowboarding. Standing high above the Green Monster, a 140-foot ski jump has been constructed in centerfield, sloping down to home plate, for the Big Air at Fenway U.S. Grand Prix event. Starting from the top of the man-made slope which stands at about the height of the upperdeck seats, competitors will descend on a 38-degree slope to 52 feet before launching into the air to do their stunts before landing near home plate. — Shawn

Ramsey, “Fenway Park transformed for Big Air freestyle ski and snowboarding jump event” (Fox Sports, February 12, 2016).