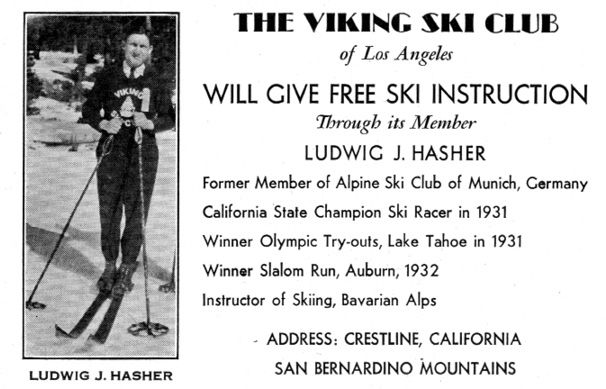

Pioneers: Vic Hasher

California's first modern-era champion and professional instructor promoted skiing for more than three decades.

Born in Munich, Germany, in 1900, Ludwig “Vic” Hasher came to Connecticut in 1926 to work as a boat builder. A year later, he was building boats in Southern California and soon joined the local Viking Ski Club. When the Depression sank the boat business, he became the chauffeur to a Hollywood movie director. But in 1931, Hasher’s livelihood burgeoned into a full-time ski career.

Photo top: Hasher and his wife, Bea, skied 1,168 miles during their first winter (1947-48) collecting snow and weather data in Mineral King Valley. All photos courtesy Katherine Hasher Kaplanek.

Here’s how: Los Angeles was scheduled to host the 1932 Summer Olympics, and California, therefore, bid for the Winter Games, too, proposing the Tahoe and Yosemite areas as venues. But the state had no skiing organization or infrastructure, so in April 1929, the International Olympic Committee named Lake Placid as the winter site. Stung by the decision, California’s ski leadership moved to create a formal organization; the California Ski Association (CSA) launched in October 1930.

The CSA held its first ski championships February 21–23, 1931, at Olympic Hill at Lake Tahoe. It was a dual meet, serving as California’s state ski championships and as the National Ski Association’s division tryouts for the Olympic ski team.

This was the heyday of North American ski jumping, so the contest included that, as well as 18- and 50-kilometer cross-county races. Hasher beat the 12 other entrants in the 18k. Two days later, he outskied three other racers in the 50k, with a time of 5 hours and 51 seconds. And he jumped in the Class B event, scoring well enough to land second place in combined.

This was Hasher’s career opportunity. In 1933, he was hired by the Los Angeles Parks and Recreation Department to be a ski instructor at Camp Seeley. This appointment made him Southern California’s first official ski instructor. As local publicity noted, “Hasher’s teaching will emphasize ski hiking and cross-country trail trips as the types of skiing most easily learned by novices, instead of the more difficult and dangerous ski jumping.” He continued to compete for the Viking Ski Club.

Skiing was catching on in California. According to ski historian Bill Berry, writing in Far West Ski News (February 15, 1973), ski clubs around the state realized that “something dramatic was needed to attract more flatlanders into the snowy vastnesses.” In 1934 and 1935, the Lake Arrowhead Ski Club hosted jumping meets at the Hollywood Bowl, and the Auburn Ski Club hosted jumping tournaments on the hills behind the University of California, Berkeley. Then in October 1937, an L.A. newspaper announced that ski lessons were available in downtown Los Angeles on the roof of the May Company department store. The slope was 15 feet wide and 84 feet long, with a vertical drop of 16 feet, and was covered with grass matting, rice hulls, borax and salt. Hasher was the instructor, attracting some of the Hollywood crowd.

The late 1930s found Hasher busy. He moved his ski school to Kerr’s Sport Shop in Beverly Hills. In 1939, he hosted lessons and a race at Manhattan Beach. Then, in 1940-41, he opened his own shop, the Big Bear Ski Hut and Alpine Ski School.

During World War II, unable to serve because of his age, Hasher worked as a tool and die maker. He volunteered for the National Ski Patrol’s “M’Aidez” search-and-rescue unit, helping to find downed aircraft in the mountains for the U.S. Army’s 4th Air Force. He proudly wore NSPS badge No. 714.

At the 1945 California Ski Association convention in Reno, Nevada, launching new ski resorts in California was a hot topic, with the top candidates being Southern California’s San Gorgonio and central California’s Mineral King, near Sequoia National Park. Leading the drive were Fay Lawrence, a Los Angeles businessman, and Corty Hill, CSA president. With Hill’s backing, the pair formed the Mineral King Corporation.

Optimism ran high about Mineral King, with some claiming it was the ideal location for the next Winter Olympics. A number of America’s best skiers agreed that Mineral King was “without peer” in the United States. Endorsers included Otto Lang, Friedl Pfeifer, Luggi Foeger and Hannes Schneider.

Lawrence explained the need for an official snow survey made by a group or individual with competent winter skills. Hasher and his wife, Bea, were chosen to spend the winter in Mineral King. “The post-war ski boom provided us with a big opportunity for adventure and pioneering,” Bea Hasher told Bill Berry. It was a “chance to spend an entire winter in Mineral King surveying the area as a potential ski development site. Vic didn’t hesitate.”

The Hashers stayed in Mineral King for the winters of 1947–48 and 1948–49. They lived in a Forest Service cabin and made daily trips into different areas of the wilderness. They were tasked with tracking snowfall, documenting weather conditions, assessing avalanche danger, identifying potential ski slopes and evaluating prospective hotel and village sites.

At the end of every day, Vic dictated the daily account to Bea, who typed up a report that was later presented to the Forest Service. According to Bea, that first winter they skied 1,168 miles. In addition to the snow and weather data, they reported there were at least 10 potential ski runs in the area, three-quarters to 3.5 miles in length, with verticals of 1,400 to 3,000 feet.

After the second winter, Hasher had high hopes that the area would soon see development. The couple moved to Sugar Bowl, near Lake Tahoe, and started a business transporting people from Soda Springs to Sugar Bowl via an Army-surplus Weasel over-snow vehicle. He worked for the Forest Service each summer.

By spring 1952, it was clear that development in Mineral King was uncertain. Hasher launched a ski-import business and planned a buying trip to Europe. He also wanted to introduce daughter Kathie, born in 1951, to his family in the old country.

The Hashers returned in October 1952, when Hasher rented a building in West Los Angeles as a warehouse for his newly christened Sports Imports. The business slowly grew. In summer 1957, Hasher met John Piane, Jr., president of Dartmouth Skis, Inc., of Hanover, New Hampshire, and signed on to become Dartmouth’s Western rep. In 1959, Hasher met Hannes Marker in Europe and secured import rights to the binding for Dartmouth. U.S. sales for Marker took off.

Hasher represented Dartmouth and Kästle Skis during the 1960 Squaw Valley Olympics, looking after Olympians from a workshop set up by Anton Kästle. Eventually, Hasher also sold Fischer skis and Obermeyer ski wear.

In 1965, with Marker, Hasher travelled to ski races in Bend, Oregon, and Sun Valley, Idaho, to recruit athletes to the binding. On March 25, as the men were returning to California through Lovelock, Nevada, their car skidded on ice and crashed into a utility pole. Marker was unhurt, but Hasher suffered

severe injuries and died the following morning, at age 64.

Ingrid Wicken has won ISHA Awards for five books. She owns the California Ski Library (skilibrary.com).