Short Turns: Labor Pains

A brief history of organized labor on the ski slopes.

National news outlets reported angry crowds in two-hour lift lines at Utah’s Park City Mountain Resort over the Christmas holidays. This high-profit part of the ski season is vital to everyone in the community. But when 204 members of the ski patrol at America’s largest ski resort went on strike on December 27, 2024, vacationers were denied access at times to up to 80 percent of the terrain due to safety closures.

Ski area owner Vail Resorts delayed negotiations with the Park City Professional Ski Patrol Association prior to the strike. The absence of patrol personnel meant that much of the resort couldn’t open. This incensed vacationers who faced the long waits on the few lifts that operated. Bad press was rampant and extended to one of CNBC’s national commentators, Jim Lebenthal. Upon returning from his family’s Park City holiday, Lebenthal blasted Vail Resorts during an early January episode of CNBC’s Halftime Report. He also cited Vail Resorts lingering low stock valuation.

Lebenthal reported that he arrived at Park City to find two feet of fresh snow. However, he was shocked and angry that less than 20 percent of the mountain was open due to the lack of patrollers. Then he issued some on-air business advice to Vail Resorts: “If you want to run a travel and leisure company, you darn well better give the experience you’re advertising. If you don’t, you will get negative PR and non-repeating customers.”

After 13 days, Vail Resorts and the patrollers’ association reached agreement on January 9, 2025. Vail agreed to raise the starting pay for patrollers and safety workers by $2 to $23 an hour, with expanded benefits, while veteran patrollers received an average increase of $7.75 per hour. But the public-relations damage had already been done.

1960s Strike Averted

Organized labor hadn’t really been a presence at American ski resorts prior to 1964, when the Aspen Mountain Employees Association formed. The new group demanded not only a raise from the minimum wage of $1.80 per hour but more than the maximum $2.05 per hour being offered. The Aspen Skiing Corporation (as it was known then) finally countered with a starting wage of $2 an hour, rising to $2.40 after three years. The Aspen Times ran a banner headline declaring “Aspen Strike Averted.”

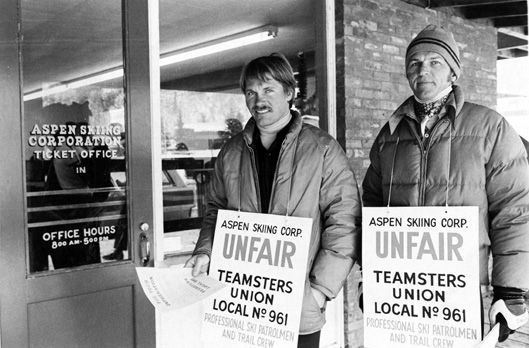

The Aspen Mountain Employees Association never officially unionized. Later, in 1971, the Aspen Ski Patrol joined the Teamsters and by December went on strike for better wages. It was a contentious time. Many Aspen residents supported the patrollers, while a lot of local burghers and ranchers opposed them. As was the case in Park City, some merchants accused the Aspen patrol of trying to sabotage the town’s most profitable part of the winter. Others felt that without a well-trained patrol who could afford to live in town, it was going to be tough to ever keep the ski areas open safely.

In Park City, the strike’s issues were bluntly put in local and national media: At their current wages, some patrollers were forced to live in their cars. And Park City isn’t the only ski resort in the country where wages don’t equate to the skills required of a patroller. A reader commented on a January 4 story in the New York Times, “I am a delivery driver and my hourly rate is $45 an hour and my job entails putting packages on people’s doorsteps. Dedicated safety professionals should not have to worry about paying the bills.”

In 1971, the Aspen Skiing Corporation acted swiftly and brought in scabs. The move, plainly a case of union-busting, saved the Christmas season. The strike and picketing continued, though with less optimism. During a hot-dog skiing contest on Aspen Mountain’s Ridge of Bell that winter, the ski patrol sent several members down the mogul-studded run pulling a toboggan with a second patroller seated in it. An onboard sign read: “You Fall We Haul, Teamsters Local 961.” It was heartily cheered, but the union conceded defeat on January 23, and many members were eventually rehired. They ditched the Teamsters affiliation in 1973.

While the patrollers’ initial goal wasn’t achieved, wages were soon brought up to the levels they’d asked for, and ski instructors got a raise, too. Other ski patrols around the country took notice. In 1978, the Crested Butte, Colorado, patrol formed a union, now one of the oldest in the ski industry. By 1986 Aspen had formed the Aspen Professional Ski Patrol Association, and Breckenridge, Colorado, patrollers followed suit the same year (Breckenridge was owned by ASC at that time).

In 1994, the ski patrol at Colorado's Keystone unionized, as did patrollers from Steamboat, Colorado, in 1998. The Steamboat chapter disbanded after a few years but eventually joined patrols at Crested Butte, Aspen, Breckenridge, Keystone and the Canyons at Park City to form United Professional Ski Patrols of America, Local 7781, a chapter of the Communication Workers of America (CWA). Keystone and Breckenridge later left to form their own unions. Patrollers at Killington, Vermont, unionized in 2001 but disbanded a year later. Telluride, Colorado’s patrol joined CWA in 2016. Washington’s Stevens Pass had been in existence since the late 1930s without its patrol unionizing, but within a year of the ski area’s purchase by Vail Resorts in 2018, patrol voted to join CWA. The ski patrol at Big Sky, Montana, successfully unionized in 2021, as did patrollers in Purgatory, Colorado, in 2022.

In 2022 electricians and lift mechanics at Park City Mountain Resort joined the patrollers in one of the first instances where non-patrollers unionized. They formed the Park City Lift Maintenance Professional Union. The following year, Crested Butte lift mechanics made the same move.

The National Ski Areas Association (NSAA), the ski resort industry’s major trade association, took notice. Its 2023 annual convention held an educational session on “Unions and the Rapidly Evolving Labor Landscape.” Statistics indicate that about 7.6 percent of ski patrollers are currently unionized, up sharply from 5.5 percent in 2021, according to industry publication Ski Area Management.

Throughout the Park City strike, social media was rife with clips of crowds chanting, “Pay your employees!” Memes also flourished, featuring “Epic lift lines,” evoking Vail Resorts’ ubiquitous marketing hook.

Industry Wage Growth

Vail Resorts could point to NSAA’s 2023 Wage and Salary Survey that showed that overall wage growth across all ski resort jobs was up 18 percent over the prior year. Wages for entry-level ski patrol jobs rose 51 percent, to $19.91 over the previous five years, and for entry-level lift mechanics 41 percent over the same time period, to $22.61. Critics countered that wages had started low and remain unreasonably low for the work at hand and for the high cost of living in resort towns.

At the onset of the walkout, Park City Chief Operations Officer Deirdra Walsh wrote in an editorial in the Park Record newspaper that, “No one wins a strike.” In the end, however, Vail Resorts capitulated. Not only did the striking patrollers win, but Vail’s corporate image was hammered.

Questions and at least one lawsuit remain. The company announced that they would give passholders credit for each day skied or boarded at Park City during the strike toward the purchase of an Epic Pass of equal or greater value next year.

Illinois resident Christopher Bisaillon wants more.

Bisaillon filed a class-action lawsuit on behalf of guests who purchased tickets during the strike, claiming that Vail Resorts “intentionally and willfully deceived hundreds of thousands of consumers” by failing to disclose the strike and the resultant conditions. “What was expected to be a dream vacation for thousands of families, at the expense of tens of thousands of dollars per family, quickly turned into a colossal nightmare,” according to the lawsuit.

Bisaillon says in the lawsuit that he spent $15,000 and skied fewer than 10 runs during a week-long vacation. He says he learned about the strike after he arrived, a day after the strike began, and that less than 20 percent of the mountain was open, which resulted in lift lines that lasted up to three hours.

Investors worry how this will impact Vail Resort’s financial performance and stock value. One of the business advantages the resort operator touts is the ability to isolate losses at one business center from the rest of the company. In a January earnings call, Vail Resorts reported a 2 percent decline in pass sales but an increase in revenue due to an 8 percent price increase, according to a report in the Wall Street Journal. Still, the company’s stock price fell about 17 percent in the immediate aftermath of the Park City strike and remains slightly above its 52-week low.

Wages and labor relations can’t be confined to one resort company, however. In a statement to the New York Times, Seth Dromgoole, the lead negotiator and a 17-year patroller at Park City, views the January settlement as “more than just a win for our team—it’s a groundbreaking success in the ski and mountain worker industry.”

Ultimately, the best business barometer for Vail Resorts will be its Epic season-pass sales for next season, which account for a majority of its annual revenue—and that’s before any lifts have spun. Though pass numbers were down slightly this season, an overall price hike more than compensated. So far that seems to be a viable mechanism for covering a lot of expenses and contingencies. Possibly even better wages.

Snapshots in Time

1937 Society’s Newest Winter Playground

When skiing became a nationwide mania in 1935, Austrian Count Felix Schaffgotsch sold Union Pacific Railroad’s 45-year-old Board Chairman Averell Harriman the idea that the U.S. deserved a winter resort like Switzerland’s St. Moritz. The result is that Ketchum, Idaho (pop. 217), has become for people who like their weather cold what Palm Beach is for people who like it hot. Sun Valley is three days from New York by train, overnight by United Airlines. — “East Goes West to Idaho’s Sun Valley, Society’s Newest Winter Playground” (Life Magazine, March 8, 1937)

1969 ‘‘Ski Stewardesses’’

In this Sussex County community where the Vernon Valley Ski Area has created a stir by introducing girls as lift attendants, almost 3,000 enthusiasts frolicked in excellent skiing conditions today. The skies were clear, the temperatures were comfortable and the waiting time at the lift lines within reason. But while Vernon Valley has all of the necessary equipment, including three chairlifts and a T-bar lift, the item that seems to be causing the most comment this season is the girl attendants. Almost all of them are students at nearby Sparta High School. “The girls prefer being known as ‘ski stewardesses,’” said Anthony Martino, president of Vernon Valley. “And we think they’re doing a great job. They’re patient with children, polite with adults and appealing to our jet set. We haven’t had a complaint about them yet.”— Michael Strauss, “Girls Give Jersey Ski Resort a Lift” (New York Times, December 29, 1969)

1978 Training-Wheels Turns

It seems that American Nordic skiers pay far too much attention to the Telemark turn. It is not really an advanced turn—my students learn it in 15 minutes, and it is really pretty limited. The Norwegian ski instructor manuals don’t even say very much about this turn. The ultimate, the expert turn, is the parallel turn. It is performed very much like a parallel turn on Alpine skis. —Vic Bein, “The New Nordic” (Powder

Magazine, November 1978)

1985 Cash-Cow Olympics

Could the Winter Olympics actually be changing to a profitable venture? Sarajevo’s Olympics Organizing Committee announced that its $96 million revenues from ticketing, licensing, TV rights, etc., were greater than its $88.2 million in expenses and that when the last $3 million or so still owed by licensees comes in, its profit will total about $10 million.—“Sarajevo Olympics Turns Profit” (Skiing Magazine, February 1985)

2024 Looking at You Middle-aged Guys On Groomers

In an attempt to see exactly who is getting injured and killed out there—and how—we dug into stats provided by the National Ski Areas Association (NSAA). The results were both expected and surprising. The NSAA compiles two fact sheets after each ski season. One reveals the number of on-mountain fatalities and the other the number of catastrophic injuries—defined as “life-altering injuries.” Of the 46 people who died at NSAA ski areas in the 2022-’23 season, 42 were male and 37 were on skis. Of the 53 catastrophic injuries, 42 were male and 44 were skiers. The majority of both incidents occurred on intermediate terrain. Here’s the twist: Most of the on-mountain fatalities during the 2022-’23 season occurred to people who were between the ages of 51 and 60. So while the stereotype is that the young guns hucking cliffs and skiing way too fast are paying the ultimate price, in reality, it’s the middle-aged guys. — “This Group of Skiers is the Most Likely to Have a Fatal Accident, according to the experts,” — Evie Carrick (skimag.com, May 15, 2024)