Sa saison 1967 est un plus grand exploit que son triplé olympique. Dans une interview exclusive, Jean-Claude Killy se souvient de la première saison de la Coupe du monde, il ya 50 ans, quand il a remporté 12 des 17 courses, y compris toutes les descentes, et a terminé sur le podium dans 89% des courses qu'il a entrées, un record qui n'a jamais été surpassé.

Interview de Yves Perret, Skiing History Magazine, 2017.

Read this story in English.

Cinquante ans après, la saison 1967 reste un des moments les plus aboutis de l’histoire du ski alpin. La première Coupe du Monde de l’histoire coïncide avec un de ses exploits les plus marquants.

Vainqueur de 19 courses sur 29, dont 12 de Coupe du Monde sur 17, et des six combinés de la saison dont la Coupe des Nations pour un total de 25 « 1st places », Jean-Claude Killy a remporté le premier globe de cristal avec le maximum de points possibles (225) soit 101 points d’avance sur l’Autrichien Heinrich Messner, son dauphin.

Autre chiffre incroyable, il a terminé 88.9% des courses ou combinés auxquels il a participé sur le podium…

En juin dernier, chez lui, à Genève, « King Killy » comme l’ont surnommé les journaux de l’époque, nous a reçus. Sur la table, il a ouvert les épais albums où sont classées avec méthode les coupures de presse qui retracent les moments forts d’une destinée hors normes. Sur un cahier où sont inscrits ses résultats, d’une écriture rectiligne, une phrase : « La victoire aime l’effort ».

Pendant plusieurs heures, Mister Killy est redevenu le meilleur skieur de la planète.

INTERVIEW

Jean-Claude, comment s’est dessinée la saison 1967 au cours des saisons précédentes?

Cela a été une lente construction, avec des étapes importantes et la même obsession : gagner.

En 1963, je termine onze fois à la deuxième place.

Les Jeux de 1964 à Innsbrück avaient été un désastre technique.

Je perds ma fixation avant dans le slalom. Je chute dans le premier dévers dans la descente. Mes carres avaient été mal travaillées.

Je finis cinquième du géant. Je n’étais pas prêt.

La semaine suivante, je remporte le Kandahar devant Jimmy Heuga, mon copain américain. Ce qui prouve que la base était présente mais que je n’avais pas encore tout résolu.

En 1964, je n’avais pas encore trouvé les solutions à mes problèmes de santé contractés durant la Guerre d’Algérie. J’étais maigre, je n’avais pas d’endurance.

Je faisais des coups comme au Critérium de la Première Neige en 1961 mais je manquais d’un système pour avoir de la constance dans les trois disciplines. Se spécialiser, c’est enlever des chances de gagner et je ne le voulais pas.

Je souhaitais mettre en place une organisation qui me permette de gommer un maximum de ces impondérables qui font la spécificité du ski alpin de compétition.

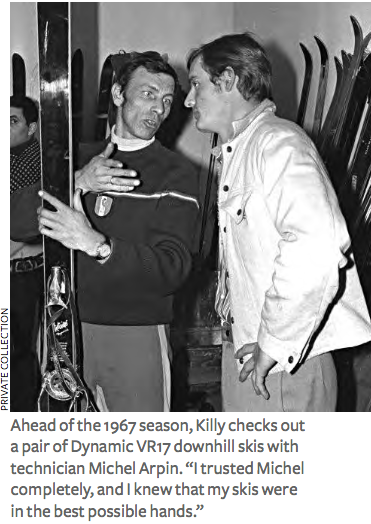

Un des moments importants fut lorsque Michel Arpin a été engagé par Dynamic pour s’occuper de mes skis. Nous étions très complices et il m’avait pris sous son aile depuis mes débuts.

Il était originaire de Saint Foy en Tarentaise, tout près de Val d’Isère, et nous parlions le même patois local. Je savais que mes skis étaient entre les meilleures mains car j’avais une confiance aveugle en lui.

Comment qualifiez-vous le processus qui vous a conduit jusqu’au sommet ?

Ma démarche était personnelle. En équipe de France, on passait tout l’hiver ensemble mais avant le premier stage d’automne, chacun avait sa façon de faire. J’étais à la recherche obsessionnellement de ce qui pourrait me faire progresser.

L’équipement était capital. Il était impératif d’avoir les meilleurs skis existants. On ne peut pas perdre une course à cause du matériel car c’est l’élément déterminant. Je skiais avec le matériel de deux marques, Rossignol et Dynamic, sans contrat d’exclusivité, ce qui me permettait de choisir à chaque course la paire qui me convenait le mieux.

Cela impliquait d’adopter une ligne de conduite différente … et de faire des sacrifices financiers dans l’instant.

En 1963, je termine même 2e du Kandahar avec des skis de descente autrichiens. A Portillo, j’ai utilisé des Rossignol en géant et des Dynamic pour les autres épreuves. Monsieur Bonnet nous comprenait. Le but, c’était de gagner des courses de ski.

J’ai toujours fonctionné ainsi. J’étais animé d’une passion débordante pour le ski, mais tourné vers la compétition.

J’ai fait l’impasse sur les études. Cela laisse du temps… mais cela ferme des portes et peut compliquer la reconversion.

La compétition était une obsession saine car je conservais ma liberté intellectuelle. Le ski était mon métier.

Pour moi, seule la victoire comptait. Je n’avais pas le choix. C’était simplement ma seule forme d’expression.

Quelles ont été les clés de votre réussite?

Quelles ont été les clés de votre réussite?

Il y a à partir de 1965, la conjonction d’éléments qui, liés, ont permis de poursuivre la montée en puissance.

L’organisation Bonnet qui nous accompagnait vers les sommets en était une.

L’industrie française qui nous soutenait avec Rossignol, Dynamic, Look, Trappeur, Salomon une autre.

Les stations françaises et les hôteliers n’hésitaient pas de leur côté à nous ouvrir leurs portes pour presque rien.

Nous entrons dans une des plus belles périodes de notre sport avec l’avènement du ski moderne.

Il y a la conjonction de moyens financiers accrus, d’hommes et de professionnels expérimentés.

La diffusion télévisée devient mondiale et contribue à faire des sportifs des mythes.

Il règne alors en France une atmosphère miraculeuse. De Gaulle l’affirme : « Nos sportifs sont nos meilleurs ambassadeurs. »

D’un coup, on passe des dortoirs de l’UCPA à un hôtel quatre étoiles.

J’ai posé une à une les pièces du puzzle et cela ne s’est fait pas du jour au lendemain.

En 1965, je suis élu Skieur d’Or Martini et Champion des Champions du journal L’Equipe, je remporte 9 victoires, je finis sept fois à la deuxième place.

Quelle est l’importance de la création de la Coupe du Monde dans la réalisation de cette saison incroyable?

Cela faisait plusieurs années que les skieurs ne supportaient plus de jouer une carrière sur une journée de Championnats du Monde ou de Jeux Olympiques. En outre, à cette époque, il était rare, par exemple, de participer à deux Jeux olympiques.

On était tous passionnés de Formule 1 et, pour nous, la référence, était le classement de la saison de ce Championnat du Monde. L’idée d’un classement sur la saison nous semblait la plus juste expression de la réalité de notre sport.

Nous avons souvent discuté de notre frustration et de ce qui pourrait résoudre le problème et il nous semblait facile d’adapter cela au ski. Le plan de la Coupe du monde de ski alpin formulé en 1966 par le journaliste Serge Lang, en collaboration avec l'Américain Bob Beattie, le Français Honoré Bonnet et l'Autrichien Sepp Sulzberger, soutenu par le quotidien sportif parisien L'Equipe et des journalistes comme Michel Clare - et John Fry, qui a ajouté la Coupe des Nations au mix, allait dans ce sens.

A Portillo, on était dans l’aire d’arrivée de la descente après ma victoire. Tout le monde pleurait. Serge Lang me demande : « La Coupe du Monde arrive. Comment vas-tu l’aborder. »

Je lui ai répondu : « Je vais la survoler… » Dans mon esprit, cela ne signifiait pas que j’allais l’écraser mais que j’allais en tirer la quintessence pour franchir une étape dans mon parcours sportif.

S’il n’y a pas de Coupe du Monde, il n’y a peut-être pas cette saison 67. C’est plus fort que Grenoble. Il n’y avait désormais plus uniquement les grandes classiques pour couronner la réussite d’une saison.

Comment qualifieriez-vous les relations au sein de l’équipe de France?

Nous étions liés à la vie à la mort. On s’entraînait ensemble, on s’affrontait tous les weekends

Aujourd’hui encore, nous restons aussi complices que des frères.

Au printemps 1966, on a skié des kilomètres au col de l’Iseran sur le glacier de Pissaillas. On s’est mutuellement nourris de nos qualités, de nos personnalités. Il y a toujours eu entre nous du respect, de l’humilité.

En 1967, Honoré Bonnet était à un an de la retraite mais le système était en place et fonctionnait parfaitement.

Michel Arpin s’occupait de mes skis et des chronos. Je savais que je pouvais m’appuyer totalement sur son savoir-faire et chacun dans l’équipe avait son rôle.

Par exemple, Melquiond apportait son calme et sa sérénité. Nous avons été compagnons de chambre pendant 7 ans sans qu’il y ait le moindre conflit d’égo.

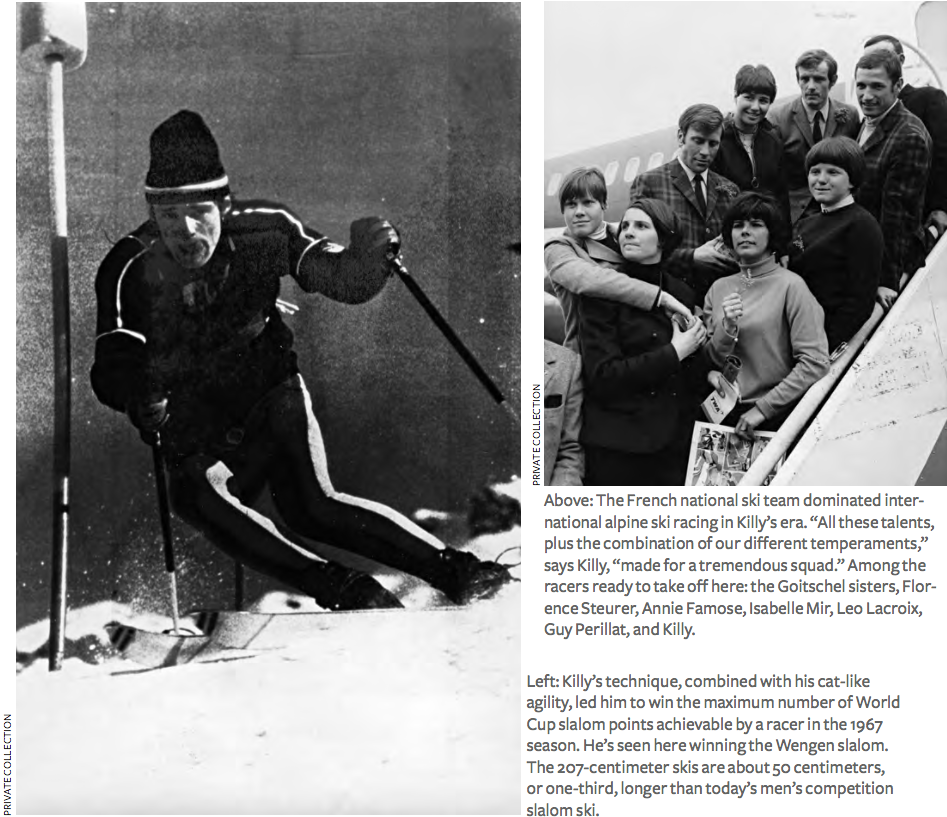

Périllat était le capitaine de route écouté et respecté.

Léo Lacroix amenait son optimisme, sa bonne humeur… et son talent.

Mauduit le géantiste et Jauffret le slalomeur étaient des skieurs magnifiques.

Tous les talents de cette équipe et ces tempéraments additionnés formaient une formidable escouade.

Abordons, la saison 1967… Débutée en décembre 1966 chez vous, à Val d’Isère, par le traditionnel Critérium de la Première Neige…

Léo dit encore aujourd’hui en riant : « Je suis le seul à avoir battu Killy en 1967 en descente » car il s’était imposé à Val d’Isère. Lorsque je le taquine, je lui rappelle que c’était en décembre 1966 …

Le Critérium ne comptait pas encore pour la Coupe du Monde. C’était un beau moment de la saison. Celui-ci est un peu particulier car c’est la première fois qu’il se disputait sur la nouvelle piste de la Daille, la Oreiller-Killy.

La Coupe du Monde débute le 5 et 6 janvier à Berchtesgaden où vous terminez troisième du géant. Mais le premier succès vient quelques jours plus tard dans le géant d’Adelboden, première victoire d’une série de huit en comptant les combinés…

Je gagne avec le dossard 13. Adelboden a toujours été une des pistes de références en géant. Y gagner, c’est valider une condition physique et des qualités. Le premier succès est un passage important.

Vous enchaînez avec deux victoires (descente et slalom) à Wengen. Quelle est l’importance de ce doublé?

Je préférais Kitzbühel à Wengen.

Dans la descente, je devance Léo de 25 centièmes. C’est la première victoire française dans le Lauberhorn depuis Guy Périllat en 1961. Elle a d’autant plus de saveur que les Autrichiens avaient qualifié notre triomphe de Portillo de folklorique et ils nous attendaient au tournant.

Pour toute l’équipe, c’est un moment important.

Je domine aussi le slalom qui est, pour moi, le plus pentu et le plus difficile de l’année.

Avec ce triplé, puisque je remporte aussi le combiné, j’ai l’impression de rentrer définitivement chez les grands.

Kitzbühel, la semaine suivante, est un moment à part. Comment l’avez-vous vécu?

Courir à Kitzbühel était ce qu’il y avait de plus excitant. On était en Autriche, pour défier des mecs qui représentaient le ski, supportés par une foule immense. On me respectait mais j’avais des rapports parfois compliqués avec le public.

Il m’est même arrivé d’envoyer Jean-Pierre Augert, qui me ressemblait beaucoup, pour traverser la foule et signer des autographes.

Gagner à Kitzbühel, c’est le rêve de tous les skieurs. Cette année-là, je remporte la descente, le slalom et le combiné et je deviens le premier à réaliser ce double triplé.

On n’a pas conscience aujourd’hui de ce que cela représente mais remporter, comme à Wengen, le combiné est important même si cela ne comptait pas pour la Coupe du Monde.

En descente, je devance Vogler d’1’’37 et je bats le record de la piste qui appartenait à Karl Schranz.

Le slalom de Kitzbühel est le plus beau. Il est très varié, avec des dévers, des changements de rythme. Il règne parfois une ambiance hostile et il faut savoir rester dans sa bulle. Je bats le Suédois Grahn, qui faisait partie des meilleurs spécialistes de la discipline de plus de deux secondes en gagnant les deux manches.

Il a régné durant ce weekend une ambiance que je n’oublierai jamais. J’ai traversé la station sur les épaules des moniteurs de ski de la station pour aller chercher mes récompenses. Cela aurait été impensable quelques années plus tôt.

« Superman sur des skis » titrait le Kronen Zeitung, un des principaux quotidiens autrichiens le lendemain.

Après ce weekend victorieux, Toni Sailer a écrit: « Killy pratique un autre ski, un ski d’un échelon supérieur à celui des meilleurs. Ses victoires sont celles d’un athlète complet arrivé à maturité. »

J’ai alors marqué 151 points sur 175 possibles. Messner, deuxième, possède 75 points.

La série continue en descente à Megève…

La piste Emile Allais est très exigeante avec son mur Bornet qui est le passage le plus difficile et le plus dangereux des descentes internationales sur lesquelles j’ai couru.

Je devance Hans Peter Rohr de deux secondes. Je réussis ma meilleure descente. Je suis étonné de l’avance. C’est ma huitième victoire consécutive et le globe de cristal de la descente est gagné.

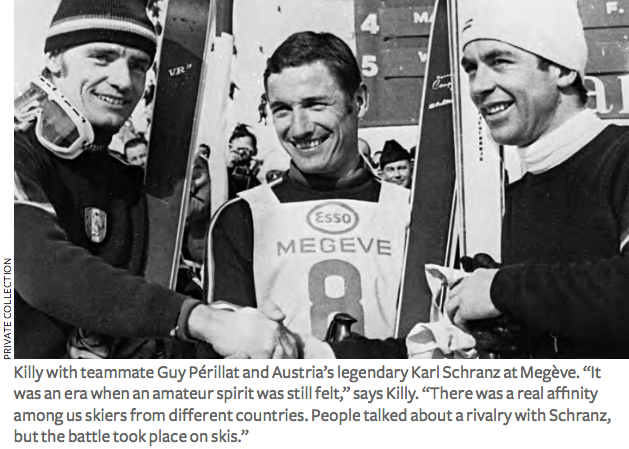

En slalom, Périllat s’impose et s’excuse de m’avoir battu. Il voulait surtout dominer Schranz, notre éternel rival. Pourtant, je suis malade, je tombe dans la première manche mais je finis deuxième quand même et je gagne le combiné.

Je déclare forfait pour les épreuves de Madonna. Je prends quinze jours de pause et je fais ma rentrée à Chamrousse pour les pré-Olympiques où je m’impose en descente.

Un jour Toni Sailer m’avait raconté qu’avant ses trois victoires de 1956 aux Jeux Olympiques de Cortina, il avait arrêté de skier plusieurs jours. « Tu devrais faire cela » m’avait-il dit. Je l’ai imité en 1967, puis, un an plus tard avant les Jeux Olympiques de Grenoble, où je m’étais échappé une semaine à Montgenèvre chez mes amis Jauffret et Melquiond pour m’éloigner du ski et de la compétition.

Durant toute ma carrière, je me suis inspiré d’autres champions pour optimiser mon ski. Zeno Colo que j’avais vu emporter le starter avec lui pour sa façon de sortir du portillon de départ, Adrien Duvillard pour sa manière de conduire le virage ou même le sauteur en hauteur soviétique Valery Brummel dont j’ai repris les exercices de weight lifting vus à la télé.

Les semaines suivantes, j’enchaîne ensuite sur le Kandahar à Sestrières avec un triplé français -Killy, Orcel, Périllat- en descente et une victoire dans le combiné très recherchée à l’époque. J’aime cette piste et l’entrée en forêt, superbe, le long des arbres.

La saison s’achève aux USA avec la traditionnelle Tournée américaine. Comment l’avez-vous vécue?

La fin de saison s’est déroulée dans la facilité. Il y a zéro doute, zéro soucis, zéro angoisse. Je suis sur un nuage.

Nous nous envolons pour les USA et c’était un moment que nous attendions avec impatience. J’étais très ami avec les coureurs américains –notamment Billy Kidd et Jimmy Heuga, le fils d’un berger basque français qui avait émigré aux Etats-Unis- qui étaient aussi de magnifiques skieurs.

Aller là-bas, traverser l’Atlantique était toujours un plaisir et une aventure. Pour ma génération, c’était un voyage important. Un de mes rêves d’enfant était de connaître l’Amérique

A la fin de cette saison 1967, cette tournée est un monument médiatique.

J’ai des propositions d’agents. On m’offre 200 000 dollars pour rejoindre le circuit professionnel et gérer une école de ski aux USA.

A l’escale de New York, une conférence de presse est organisée. Nous sommes reçus par le gouverneur du Massachussets.

On attend beaucoup de moi mais je dois rester concentré.

Dans Sports Illustrated, dont j’ai fait la couverture à trois reprises au cours de ma carrière, on peut lire des titres comme « Lafayette, they are back » ou « King Killy ».

Mais pour moi, il s’agit de ne pas perdre le fil de la saison et de terminer le boulot.

L’étape de Franconia est importante…

Je gagne la descente. Une section difficile de la piste de Cannon Mountain est rebaptisée « Killy’s Corner» (Virage Killy). Cette fois, c’est sûr, je gagne la Coupe du monde.

Je remporte aussi le géant, le slalom et le combiné. Ce sont des moments de plénitude rares mais la saison n’est pas encore terminée.

Il reste pourtant deux dernières étapes à Vail et à Jackson Hole, comment les abordez-vous?

La Coupe des Nations devient un enjeu pour nous qui nous pousse à ne rien lâcher. L’équipe de France s’impose et c’est toujours un bon moment de gagner collectivement.

A Vail, je gagne deux géants, une descente et un slalom.

Evian, le commanditaire de la Coupe du Monde, offre le voyage à Robert, mon père, qui amène le globe de cristal à Jackson Hole.

Là-bas, j’étais fatigué, j’avais souffert d’une sinusite les jours précédents.

Je reconnais la descente … en luge pour ménager mes forces et prendre un peu de bon temps.

A Jackson Hole, je gagne encore un géant.

La saison est finie ou presque puisqu’il me reste encore des courses en Suisse à mon retour à Verbier où je gagne, et à Thyon, où je suis battu par Mauduit.

Mais c’est durant la tournée américaine que le « boulot » a été terminé.

Je suis heureux de partager du bon temps avec mes copains.

Quels ont été vos adversaires durant cet hiver magique?

C’est une saison d’une incroyable densité avec 14 skieurs issus de sept nations, qui ont pris la deuxième place des courses que j’ai remporté.

Heinrich Messner a terminé à la deuxième place du classement général de la Coupe du Monde. C’était un skieur « classique », un homme discret mais toujours régulier et difficile à battre.

Je me suis retrouvé à quatre reprises sur la plus haute marche du podium accompagné de mon grand copain Jimmy Heuga. C’était une époque encore « amateur » dans l’esprit. Il y avait une vraie complicité entre les skieurs de toutes les nations avec lesquels on partageait de très beaux moments.

Une fois sur la piste, nous devenions adversaires, sans que cela n’altère nos relations. On a parlé de rivalité, notamment avec Karl Schranz mais la bagarre, c’est sur les skis qu’elle avait lieu. Le reste du temps, on s’entendait vraiment bien. Avec tous les skieurs de cette époque, nous avons des dizaines de souvenirs en commun, de fous rires partagés et d’anecdotes.

Cette saison incroyable a déclenché une médiatisation et notoriété hors normes. Comment l’avez-vous gérée?

Cela a vite débordé du cadre du ski alpin. A partir de Wengen sont arrivés des médias qui n’étaient pas ceux qui nous suivaient d’habitude comme Paris Match ou l’émission de télé très populaire en France Cinq Colonnes à la une.

Aujourd’hui, on parlerait de presse « people » qui voulait tout connaître de nous et pas seulement de nos vies de sportifs.

En janvier, au Tenne, à Kitzbühel, où nous avions l’habitude de fêter nos succès, Perillat m’avait mis en garde : « Fais attention, ne t’occupe pas de ce qui se passe autour. Cela m’a coulé après ma saison 1961 (nldr : durant cette saison, il avait remporté toutes les descentes avant de connaître un passage à vide de plusieurs saisons). Mais je sais que cela ne t’arrivera pas car tu sais faire la part des choses. »

1967 m’est tombé dessus et j’ai appris à composer avec la présence constante des envoyés spéciaux de toute la presse française et internationale. Il fallait être capable d’ « ouvrir » les portes puis de les refermer. C’est également ce que j’ai fait la saison suivante à Grenoble. Trente minutes de point presse chaque jour et c’est tout.

Quand avez-vous pris conscience du caractère exceptionnel de cette saison 67?

Je ne l’ai jamais perçue dans sa totalité. Je ne me suis pas rendu compte de ce que j’ai réalisé. Bien sûr, il y a des chiffres : 12 de Coupe du Monde sur 17, vainqueur de 19 courses sur 29, et six combinés de la saison pour un total de 25 « 1st places.»

Mais je ne me suis jamais dit « C’est fantastique »

Il m’a fallu 50 ans pour m’apercevoir que cela n’était pas commun.

Chaque époque possède ses challenges. Longtemps, ce qui m’a hanté, c’est ma deuxième place en descente à Kitzbühel en 1968. Cela m’a rendu malade. Comme quoi l’esprit se focalise parfois sur des anecdotes.

La saison 1967 est posée dans mon histoire sportive entre les Championnats du Monde de Portillo en 66 et les Jeux Olympiques de 1968. Elle fait face aux objectifs d’une journée, les fameuses « courses du jour J ». Ce sont, pour moi, des exploits qui vivent bien les uns à côté des autres et se complètent.

Finalement, 1968 à Grenoble, c’était assez « simple »… Il y avait trois courses, dans un laps de temps déterminé, à une date connue bien à l’avance, avec un objectif finalement assez clair.

1967, c’est une construction plus compliquée, plus élaborée…

Les comparer, c’est comparer un sprint et un marathon.

A l’été 67, je suis passé à autre chose assez vite. J’avais une passion immodérée du sport automobile. La Targa Florio, Monza, les 24 Heures du Mans, le Nurbürgring au volant de Porsche ou d’Alpine. C’était bien de vivre d’autres moments, d’autres sensations, d’autres défis.

Aujourd’hui, c’est en me replongeant avec plaisir 50 ans après à la demande de Skiing History dans cette saison incroyable que je me rends compte que ce n’était pas si mal. Thank you, guys !

Yves Perret, qui dirige une agence de médias sportifs à Grenoble, est l'ancien rédacteur sportif du journal Dauphiné Libéré et rédacteur en chef de Ski Chrono.