When it comes to trail monikers, no lions and tigers, but plenty of bears—not to mention resort founders, historic events and death threats.

By Jeff Blumenfeld

I remember December 1973 like it was yesterday.

While on Christmas break from Syracuse University, a buddy and I decided to fly cross-country, stay at Utah’s Snowbird Cliff Lodge, and ski something bigger than what we were used to in Central New York.

It didn’t work out that way.

Instead of skiing, we spent three days shuttling between our hotel room and the basement as ski patrollers used explosives to trigger controlled avalanches. It sounded like we were under attack. Little Cottonwood Canyon was closed and wealthier guests were renting choppers to descend to Salt Lake City.

One avalanche gained more power than the patrol expected. It damaged Alta Lodge, filled four rooms with snow and severely injured a lodge employee. It also partially buried a housing trailer where two co-workers were caught in flagrante delicto. Today that slide zone is colloquially referred to as Valerie’s Climax among those who were there.

All these onomastics got me wondering: Where do trails derive their idiosyncratic names? An informal Skiing History poll of resorts indicates that trail names generally honor founders, long-serving employees and historic events; a unique mountain feature or fauna; or warn that you just might die on the descent.

Honoring History

Several trails at Vermont’s Bromley Mountain commemorate the late Fred Pabst Jr., of Pabst Blue Ribbon beer fame, who opened the ski area in the late 1930s as part of his growing Ski Tows, Inc. empire. After you ski Pabst Panic, Pabst Peril and Blue Ribbon, you can knock back a PBR on tap at the Wild Boar Tavern or Sun Deck Bar.

Several trails at Vermont’s Bromley Mountain commemorate the late Fred Pabst Jr., of Pabst Blue Ribbon beer fame, who opened the ski area in the late 1930s as part of his growing Ski Tows, Inc. empire. After you ski Pabst Panic, Pabst Peril and Blue Ribbon, you can knock back a PBR on tap at the Wild Boar Tavern or Sun Deck Bar.

Just up the road at Pico Peak, the late Karl Acker, who served in the U.S. Army’s 10th Mountain Division for three years during World War II, was a downhill and slalom champion, and as ski school director would later purchase the ski area with his wife, June Acker. He’s remembered by an expert summit trail called Upper KA, which turns into an intermediate run lower on the mountain.

Utah’s Deer Valley has Stein’s Way, named after its late director of skiing, Stein Eriksen. The resort’s late founder, Edgar Stern, is honored with Edgar’s Alley. And if you ski or ride Colorado’s Copper Mountain, you get a sense of the reverence placed upon Charles D. Lewis, former executive vice president and treasurer of the then-fledgling Vail Ski Corporation. In 1969, as founding CEO of Copper, he developed the ski area “from the ground up,” according to the Colorado Ski & Snowboard Museum Hall of Fame. The CDL trail is off the Excelerator chair in Spaulding Bowl.

Back at Utah’s Snowbird, Junior’s Powder Paradise pays homage to Junior Bounous, the resort’s first ski school director and a pioneer in the ski industry who was inducted into the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame. Alice Avenue is named for founder Dick Bass’s wife, whom he called “sweet Alice from Dallas.” Bassackwards is named for Bass himself.

The list goes on and on. Want a ski trail named after you? Clearly, it helps to start a ski area.

And with so many U.S. ski areas founded by veterans of World War II, it’s not surprising to learn of trails commemorating that conflict. Riva Ridge on Colorado’s Vail Mountain, for example, is named after the site of the 10th Mountain Division’s first victory, a surprise 1945 night climb and dawn attack on the steep Apennine plateau north of Florence in north-central Italy.

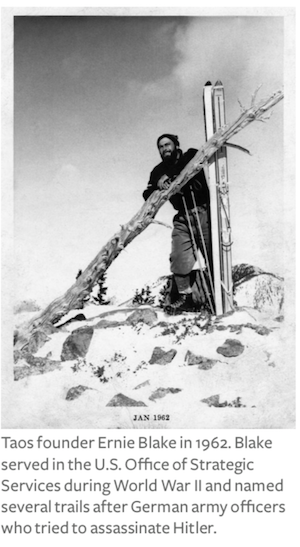

At Taos Ski Valley in New Mexico, the Stauffenberg trail is named for German army officer Claus von Stauffenberg, who unsuccessfully tried to assassinate Adolph Hitler on July 20, 1944. The story of that effort to change the course of history was depicted in the 2008 film Valkyrie, with Tom Cruise in the lead, and the 1951 film The Desert Fox. Other trails, some of Taos’ most challenging, commemorate the roles of three additional anti-Nazis—would-be assassins Hans Oster, Fabian von Schlaberndorff and Henning von Treskow. A bit lower down, Walkyries Bowl and Walkyries Gulch are named for the assassination plot itself, Operation Valkyrie.

At Taos Ski Valley in New Mexico, the Stauffenberg trail is named for German army officer Claus von Stauffenberg, who unsuccessfully tried to assassinate Adolph Hitler on July 20, 1944. The story of that effort to change the course of history was depicted in the 2008 film Valkyrie, with Tom Cruise in the lead, and the 1951 film The Desert Fox. Other trails, some of Taos’ most challenging, commemorate the roles of three additional anti-Nazis—would-be assassins Hans Oster, Fabian von Schlaberndorff and Henning von Treskow. A bit lower down, Walkyries Bowl and Walkyries Gulch are named for the assassination plot itself, Operation Valkyrie.

Owner Ernie Blake (formerly Bloch, a Jewish Swiss Air Force vet) served in the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS) during the war. Think of him when descending Ernie’s Run off Lift 5 from the base. When liftlines were long at Taos, he was known to distribute cookies to waiting skiers.

The rich mining history of many western resorts is also reflected in trail names. At Snowbird, Big Emma is named for the beloved local madam of Alta’s mining days—back when brothels were euphemistically known as “sporting clubs.” Meanwhile, West 2nd South, an easy run, was named for the location of the red light district.

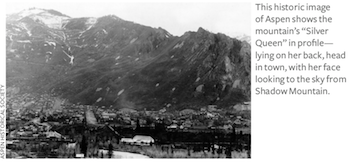

The Silver Queen run at Colorado’s Aspen honors the largest silver nugget ever mined (1,840 pounds). A massive statue made from the nugget traveled to the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 but mysteriously disappeared and never made it back to Aspen. The trail also pays homage to the imaginary profile of Aspen Mountain, first coined the “Silver Queen” in the 1880s, lying on her back, head in town, with her face looking to the sky from Shadow Mountain. In 1950, the trail was the site of the first GS race ever contested in a FIS World Championship. Ruthie’s Run was named for the wife of Aspen pioneer David R.C. Brown and also a piste for many hotly contested World Cup races and the 1950 FIS championships—the first held in North America.

Bears are Big

Bears are big at Vermont’s Stratton. The Algonquin name of the resort itself is Manicknung, which means “home of the bear,” and references to our ursine friends adorn the logo, trail signs, website and all sorts of swag. Stratton is also the location of a bear travel corridor, part of a six-year radio telemetry study that provides data important for land use planning across the state and led to conservation easements on more than 1,000 acres of prime habitat around the mountain, according to senior manager Myra Foster.

There are trails named Bear Bottom, Bear Down, Black Bear, Dancing Bear, Polar Bear, and the Ursa Express lift. Sure to baffle any Millennial, Gentle Ben was named for the bear character created by author Walt Morey and first introduced in a 1965 children’s novel, a 1967 film, and a popular late 1960s U.S. television series of the same name.

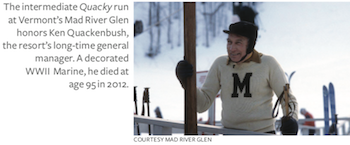

When you ski Vermont’s Mad River Glen, you’ll likely ski on an animal-themed trail such as the Beaver, Bunny, Ferret, Fox, Gazelle, Loon, Lynx and Wren. One trail performing double duty is an intermediate run named Quacky, which actually honors long-time general manager Ken Quackenbush, an iconic figure in MRG’s history and a decorated World War II U.S. Marine who died at age 95 in 2012. In her book A Mountain Love Affair: The History of Mad River Glen, author Mary Kerr calls Quackenbush the “glue and the conduit that have held Mad River Glen together for forty-five years under three owners.”

When you ski Vermont’s Mad River Glen, you’ll likely ski on an animal-themed trail such as the Beaver, Bunny, Ferret, Fox, Gazelle, Loon, Lynx and Wren. One trail performing double duty is an intermediate run named Quacky, which actually honors long-time general manager Ken Quackenbush, an iconic figure in MRG’s history and a decorated World War II U.S. Marine who died at age 95 in 2012. In her book A Mountain Love Affair: The History of Mad River Glen, author Mary Kerr calls Quackenbush the “glue and the conduit that have held Mad River Glen together for forty-five years under three owners.”

Abandon All Hope

There’s a signpost above the gates of Hell, writes Italian poet Dante Alighieri in the allegorical epic poem Divine Comedy, published in 1472. It says simply, “Abandon All Hope, Ye Who Enter Here.” An apt description of our final category of trail names, namely, those that predict imminent doom ahead.

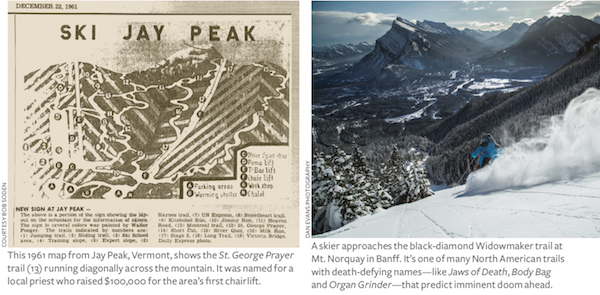

If you’re a happily married man, think twice before descending the black diamond Widowmaker trail, located at Mt. Norquay in Banff, Alberta, and accessible off the North American chair. It’s one of the last in-bound runs on the south side of the resort and offers jaw-dropping views of the town of Banff.

“The trail has a very steep drop-off turn to the left, coming back over 90 degrees. If you missed that turn in a downhill race, you’d go airborne, probably hitting the trees about 10 feet above the ground,” says ISHA board member Wini Jones, who grew up skiing in Alberta and spent 30 years at Roffe Skiwear in Seattle as vice president for design and marketing.

A former instructor at Zermatt and Innsbruck, Jones also remembers the mid-1980s day in the Selkirks out of Revelstoke, British Columbia, when Selkirk Tangiers Heli Skiing introduced her to a 2,000-foot fall line run called Holy Sh*t.

“When you got out of the chopper and looked down at 2,000 feet of virgin powder, guess what everyone said?” she laughs. These days, sales manager Emma Mains says the run goes by the moniker Deep Sh*t.

Rather than face annihilation, you can hedge your bets by skiing the intermediate St. George Prayer trail at Vermont’s Jay Peak. Around 1960, after Jay had previously installed a pomalift and then a T-Bar, it was decided that to join the big leagues, Jay would need a chairlift, according to ISHA board member and ski historian Bob Soden, an engineering consultant from Montreal. Father George St. Onge, a priest from nearby Richford, Vermont, led the fundraising committee.

“Father George was no ordinary man of the collar—he drove a sports car with panache, wearing a large grin, a tweed cap and a flowing scarf. He was given one year to raise $100,000 for the lift,” Soden says. “He drove a tough bargain and left no stone unturned, held fundraiser after fundraiser and called in every favor owed—and he met the deadline.”

To honor his tenacity and faith in the project, Jay Peak’s then general manager, Walter Foeger, named the most prominent trail from the top of the Bonaventure chairlift St. George’s Prayer.

The list of death-defying names is endless in a sport that prides itself on safety initiatives. There’s Harakiri at Mayrhofen, Austria, named for the Japanese ritual samurai suicide by disembowelment; the sphincter-tightening Jaws of Death at Vermont’s Mount Snow; Organ Grinder and Exterminator at Sugarbush, Vermont; and Body Bag at Crested Butte in Colorado.

Golf uses numbers to identify holes; the same with tennis, squash and racquetball courts. Bowling lanes are always numbered. How boring. Skiers and riders are born storytellers. Just visit any après ski bar: When a resort plays the name game, a creative trail moniker makes any day sound twice as epic.

Jeff Blumenfeld, a resident of Boulder, Colorado, founded Blumenfeld and Associates PR, LLC, in 1980. He is chairman of the Rocky Mountain chapter of The Explorers Club and edits Expedition News, a monthly review of expeditions and adventures (expeditionnews.com).