Dynamic Reinvents the Slalom Ski

The VR17, engineered for French ski racers, was imitated by ski factories around the world.

From the January-February 2022 issue

The Dynamic VR17 remains legendary, and for good reason. With its hickory core, fiberglass torsion-box construction, “cracked” flexible edge, stiff tail and rear-waisted sidecut, the ski set the standard for slalom performance beginning in 1966. For the next two decades most of the slalom racing skis built around the world copied the VR17’s design details. VR17 clones, exact or approximate, were made by Dynastar, Lange, Head, Durafiber, K2, Völkl, Fischer, Atomic, Blizzard, Hexcel, Olin, Elan and possibly others.

Photo top: Billy Kidd en route to the 1970 combined world championship, on the VR17.

The ski was developed in the tiny agricultural commune of Sillans en Isère, population about 830. Sillans lies about 10 miles west of Voiron, where Abel Rossignol had been manufacturing skis since 1907. Two significant workshops comprised most of what might be called industry in Sillans. The Carrier family made shoes for farmers and hunters, and right next door the Michal family made wooden shuttles for the silk factories of Lyons and, occasionally, furniture.

Carrier out for a stroll. Courtesy J-C Verhilac.

Marcel Carrier, representing the third generation to manage the shoe factory, ran off at age 17 to fight in World War I. Returning in 1918 he was enamored of skiing and started to make ski boots. In 1930, with Alpine racing just emerging as a high-speed spectator sport (see “Alpine Revolution,” January–February 2021), Carrier recognized that the new Kandahar cable bindings, which fastened down the heel, would need stiffer, more specialized ski boots—and he made them under a new label, Le Trappeur. In 1931 he approached 19-year-old Emile Allais, the rising star of French ski racing, who agreed to use the new boots. The following year Carrier began marketing the boot in North America; the success of the brand helped Sillans weather the Depression.

After Allais visited the shop in 1931, Carrier popped next door and asked his close friend Paul Michal, then training to take over the family woodworking shop, to make some skis. Michal knew little about skiing, but local ski champion André Jamet loaned him a pair of Norwegian skis to copy. Michal found making skis far more interesting than turning out shuttles and bobbins (just as Abel Rossignol had done a generation earlier). With his brother-in-law, Jean Berthet, in 1934 he began selling Alpine skis under the brand name Skis M.B. (Michal and Berthet). In 1937, the brand name became Nivôse. Derived from the Latin word for snowy, it was the name of his distributor, a new ski-clothing company in Lyon.

After 1934, with the introduction of laminated skis, ski-making on an industrial scale became an innovative business. Rather than license the Splitkein patent for laminated skis, Dynamic continued to carve skis from single planks, in hickory or ash. In 1936, in order to more accurately pair skis, Michal invented a “dynamometer,” a device to test the flex of each ski before the final varnish sealed the matching serial numbers. And he rebranded his skis as Nivôse -Dynamic, for “DYNAmometer” and “MIChal.” It was the first Alpine Olympic year.

Dynamic K, with Cellolix base and

channels for the continuous edge. From

George Joubert's book Modern Technique,

1957.

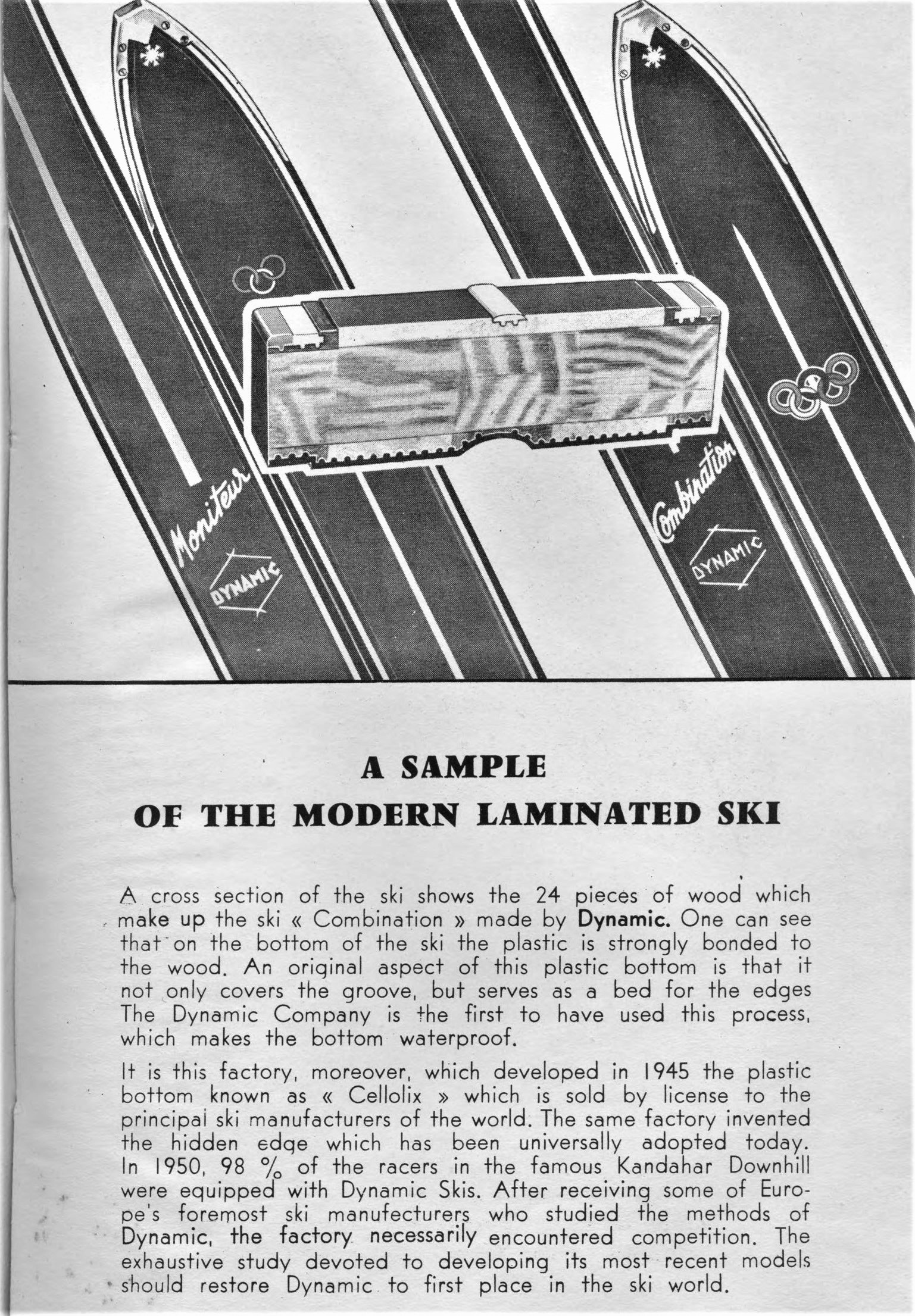

During World War II, ski production ceased as the Nazis forced Michal to make wooden shoe-soles for export to Germany. After Liberation in August 1944, he was reluctant to resume making the old pre-war ski designs. Michal resumed production, now building skis with 24 hardwood laminations. (Berthet remained a partner but left Sillans to run a factory in Reims). In 1946, Michal hired downhill world champion James Couttet as ski tester and technical adviser.

Michal and Couttet hoped to improve glide speed, and among other solutions, Michal sought out Xavier Convert, who manufactured celluloid plastic for combs. Convert was trying to revive business for his factory in Oyonnax, which today is the center of the French plastics industry. He proposed to create solid celluloid bases for skis. Celluloid would make a tough and permanently waterproof base that should also glide well.

Little was known about how to make a ski glide faster, other than to paint on a slick waterproof lacquer and hit the right wax (see “Walter Kofler Invents the Polyethylene Base,” November–December 2021). Insulating bases did work better than heat-conducting surfaces like aluminum and steel, however, so a plastic armor plate showed promise. The new “Cellolix” base offered an advantage to racers, especially in combination with a new Michal invention: the hidden, low-drag continuous L-section edge. Michal applied for a patent on the edge in 1949 and built the Dynamic K race ski with it beginning around 1950. Recreational skiers, however, didn’t see a reason to pay extra for that edge, and eventually he let the patent lapse. Truth be told, Michal wasn’t interested in selling recreational skis. If a ski worked for racers, he claimed, it should work for every skier.

Michal thought of himself as an artisan in wood, tweaking his skis to meet the needs of the ski racers who came to Sillans to talk to him. In the years before bombed-out Austrian factories rebuilt, Michal equipped Austrian as well as French racers. By 1950, dozens of top racers from all the Alpine nations rode to victory on Dynamic’s K model, with 24 laminates of hickory, continuous edges and Cellolix bottoms. The list included Othmar Schneider, Anderl Molterer, James Couttet, François Bonlieu and Charles Bozon. Then in 1954 Austrian and Swiss skiers got Kofix polyethylene bases and Dynamic lost its speed advantage. Dynamic finally offered polyethylene as an option on the ash Slalom Leger and hickory Slalom Géant in 1959. Michal called the new base Polyrex.

at the 1960 Olympics, on wooden

Dynamics. Two years later he won the

slalom world championship. Club des Sports

Chamonix-Mont Blanc

By 1950, metal skis were edging into the market, in part because celluloid had solved the problem of bare metal’s poor glide. Michal was never a fan of metal in skis, and around 1955 he turned his attention to fiberglass, partly at the behest of Claude Joseph, who manufactured polyester resin and corrugated fiberglass panels. Progress was slow, based on trial-and-error tests with racers, notably Olympic medalist Charles Bozon. In 1960 Michal realized that he needed a more systematic approach to product development. He took a number of structural engineering courses at the University of Grenoble, focusing on spring rates and inertia. He also hired Michel Arpin, the racer who had become Jean-Claude Killy’s mentor and technician.

In 1963 the team built the glass-wrapped polyester-resin/fiberglass Compound RG5 racing ski, built by Dynamic in Sillans. Joseph founded Dynastar, in Sallanches, to make the consumer-sales version. The name meant resin-glass, five years in development.

Dynamic and Dynastar parted ways. In 1964, Michal introduced the VR7 as Dynamic’s new race ski, largely of Bozon’s design. The name meant Verre Resine (resin glass), seven years in development.

That summer, Bozon was one of 14 climbers killed in an avalanche above Chamonix. Michal’s son Jean joined the company and created its first logo, the familiar double-bar chevron.

Arpin, with Killy’s input, created the VR17 to help racers take full advantage of the new forward-canted boots and avalement technique (see “Le Trappeur Elite” and “Avalement,” July–August 2021). The VR17 moved the waist back from the ball of the foot to the heel, because that was where French racers were driving the turn, and for the same reason had a stiffer tail. The ski was also built with tough epoxy rather than polyester resin, and – perhaps most important -- had a new super-flexible “cracked” edge—one continuous piece of steel with segments engineered into the visible part of the L-shape. This construction took the vibrational frequency of steel out of the ski’s dynamic behavior, letting the glass-wrapped box dampen chatter at its natural rate. Because the edge no longer contributed to lengthwise flex, the ski was made thicker, which significantly increased the torsional stiffness. The segmented edge also cut into ice like a serrated knife.

among Dynamic's race stock VR17

inventory. Private collection.

In 1966 Arpin dropped off the ski team to work full time building skis for Killy and a few more top French skiers, at a time when the team, and Killy in particular, dominated Alpine racing season after season. Racers weren’t allowed to endorse products directly, so French skiers were free to use Rossignols or VR17s, depending on which they felt would be fastest on the day’s course conditions.

In 1963, Michal turned over day-to-day operations to his son Jean, and served as fully involved chairman. He still focused on race skis, built by a small, elite crew headed by Paul Serra. But Michal, at heart an artisanal woodworker, regarded every Dynamic ski as a custom build for some racer, somewhere. The torsion box had been a genius idea: fiberglass wrapped around the core eliminated any chance of structural delamination, and the glass fibers could be spiral-wrapped to fine-tune the balance between torsional and beam flex. Racers like Killy and Billy Kidd won races and championships on their Dynamics, and other factories imitated the design.

Paul Michal retired for good in 1967. Under Jean Michal’s management, sales boomed. In 1969, Bob Lange signed a contract to import Dynamic to North America and even to build VR17s in his new factory in Broomfield, Colorado.

The market became increasingly competitive, and rival brands sold many thousands of recreational skis to subsidize their custom-built race models. Paul Michal’s assurance that anyone could ski on the VR17 was pure nonsense. The ski required strength, speed and catlike reactions. “It rewards brilliance and punishes mediocrity,” said one wag at the time.

But expert skiers around the world wanted VR17s, and the factory couldn’t meet demand. U.S. production stopped when Lange lost control of his company in 1973. Ian Ferguson, Lange’s sales manager, noted that manufacturing quality for consumer-market skis deteriorated, at least in the Boulder factory. The assembly process was sloppy, he said. A worker wrapped the core in the requisite layers of fiberglass cloth, soaked it with liquid resin and placed the assembly in the mold. Variations in the resin volume plus wrinkles, folds and air bubbles made the ski’s ultimate flex and strength unpredictable. Pair-matching wasn’t precise, either, because skis were measured for shovel and tail flex but not for full-length flex or torsion.

In 1971, to finance larger production, the partners Paul Michal, Jean Berthet and Marcel Carrier sold a share of the company to an investment group. Within a year, they sold all their shares, leaving the new management company in control. Jean Michal left, in disgust, in 1973.

The fact was that cloned designs from other factories worked just as well and had better quality control. Eventually a mass-production version, the VR27, was marketed worldwide, along with a series of softer recreational skis.

Unable to expand production profitably, the new owners sold the company to Atomic in 1988. Atomic moved production to Austria and closed the Sillans factory in 1994.

Today you can find the Dynamic VR17 brand on boutique skis made in Italy. As for Paul Michal, he remained innovative, filing for a patent as late as 1975. He died in 1983.

Sources for this story include Jean Michal; Nicole Chabah: Sillans, petite cite de grandes aventures (Editions Alzieu 2000); Juliette Barthaux, L’innovation dans l’histoire du ski alpin (unpublished master’s thesis, 1987); and interviews with Michel Arpin, Ian Ferguson and Maurice Woehrlé. Many thanks to Albert Parolai and Jean-Charles Verhilac for research assistance.

Seth Masia, president of ISHA, wrote about Kofix in the last issue of Skiing History.

Une Histoire des Skis Dynamic

By Jean Michal

Reviewed by Seth Masia

The skis that led the fiberglass revolution of the 1960s were Rossignol’s Strato, Kneissl’s Red Star and especially Dynamic’s VR17. The VR17, which introduced the cracked edge, torsion box construction and tail-biased flex and sidecut designs, became the pattern for top-performing slalom race skis for the next three decades.

I outlined the story of that ski in the January 2022 issue of Skiing History, but barely scratched the surface. Now Jean Michal, 92-year-old son of Dynamic’s founder and inventive spirit Paul Michal, has published a 280-page history of the company, in French. Michal was the first ski designer to flex-test skis for pair-matching, to introduce a plastic base material that was really faster than waxed hickory, to patent a one-piece “hidden” edge for better glide speed; he invented the torsion box construction and the cracked-steel edge—and he worked hand-in-glove with the world’s best ski racers to help them go faster.

Paul Michal was born in 1902, son of a cabinetmaker and portrait painter who taught those arts in Paris and Quebec. The family returned to their home town, Sillans-en-Isère, in 1923, and set up a shop to build fine furniture and cabinetry. That didn’t pay the bills, but they established a profitable sideline making shuttles for the silk-weaving industry. Paul Junior studied engineering at a technical school in Grenoble, where he met fellow-student Jean Berthet. Upon graduation, Berthet took a job as a mining engineer, and in 1929, married Paul’s sister Jeanne; the following year Paul married the local schoolteacher.

The financial crisis of 1929 closed the mines; the Berthet family returned to Sillans to join the Michal family business. In 1931, Paul’s neighbor and friend Marcel Carrier brought around a pair of skis he wanted duplicated. The shop ran off a few pairs—and the 17th-century barn became a ski factory.

Jean Michal was born at the end of that year, but his mother soon died of a postpartum infection. Heartbroken, and with the woodworking business in Depression-era tatters, Michal talked Berthet into a trip to the Soviet Union, planning to build the Russians a shuttle factory to serve their emerging weaving industry. It didn’t work out: Berthet went home after six months, after realizing that his coworkers were disappearing into the Gulag; Michal lasted another year.

By 1934 the partners were trying to rebuild the Sillans business, under the name Michal, Berthet & Cie., when Michal, while cleaning his motorcycle next to a wood stove, accidentally ignited himself and the factory. He survived second-degree burns to his hands and arms and a near-fatal bout with tetanus. In rebuilding the factory they laid out a more rational system for making skis. Michal supervised technical matters, Berthet assumed responsibility for administration, finance and sales. By this time, skiing was becoming a popular sport, and a real business: the neighboring Carrier shoemaking factory was busy cranking out Le Trappeur ski boots. In 1937 Michal, Berthet forged a distribution deal with a firm in Lyons eager to sell waterproof skiwear under the Nivose (“snowy”) label. Skis M-B became Skis Nivose.

Michal made skis the old-fashioned way, carving them from single planks of hickory (for racers) and ash (for recreational skiers). This meant that each ski’s flex was in some measure determined by the density and pattern of its wood grain. To match skis accurately into pairs, he needed a reliable way to determine their flex. He came up with a machine to flex-test each ski and then stamp a pair of numbers on it: shovel flex and tail flex. A worker could then sort and pair skis by their flex codes. The device was gradually improved and Michal called in a dynamometer; and the skis were renamed Nivose Dynamic (for Dyna-Michal).

Sales picked up; the factory expanded. The production crew of a dozen or so was augmented after each late-summer harvest, when local farmers pitched in to make skis. When France went to war in 1939, most of the workers went into the army; Berthet managed to sell most of the inventory to a Swiss importer, before going into the air force, flying in a reconnaissance squadron. Most of the squadron’s crews were shot down by Messerschmitts; three planes escaped to North Africa, where Berthet demobilized and found a job selling metal products for a French firm.

Back home, the French population was largely impoverished by the German occupation. Michal found a market for wooden shoe-soles, as a substitute for good-quality leather products. Late in the war, the Germans demanded a shipment, and Michal had to comply. The maquis mysteriously got wind of the deal and a railroad car full of shoe soles was burned.

After Liberation, Berthet decided to remain in the metals business, working at Tissmetal in Lyon, but stayed on with Dynamic part-time as a management consultant. The company became Ateliers Michal, and the boss designed a laminated ski, built with 24 strips of ash and hickory, glued together with a high-tech adhesive developed during the war to hold aircraft together, notably the DeHavilland Mosquito. The build process for Dynamic skis was labor- and time-intensive, but it made for a stronger, lighter product and most important, a more consistent flex. Every ski flexed as the average of the laminations, so there was much less variation between skis. Moreover, pairs could be matched closely for flex and liveliness by building them from paired laminations: when a strip of wood was sliced lengthwise, one half went into one ski, the other half into its mate.

Michal also lost no time getting a pair of skis to James Couttet, who loved them. At age 16, Couttet had won the 1938 downhill championship, only to have his career interrupted by the war. Now 24, going into the 1945-46 season, he was ready to pick up where he’d left off, and worked with Michal to develop the fastest-gliding skis possible. Michal started by looking for a tough, waterproof plastic base that would hold wax. In the era before polyethylene, the best plastic available was celluloid – tough enough for billiard balls, piano keys and film stock. He contacted a Xavier Convers, who manufactured celluloid products in Oyannax. Convers agreed to supply “Cellolix” bases, and also recommended celluloid top edges to protect the ski tops. Production began in 1946.

At the same time, Michal wanted to eliminate the snow drag of segmented steel edges with their numerous exposed screw-heads. He doodled up several designs for “hidden” continuous edges, which could be glued under the edges of the plastic base. Moreover the exposed steel surface was much narrower than the draggy screwed-on edges. In 1949 he took out a French patent on the idea. With these inventions – Cellolix, smooth continuous edges. By that time Couttet had used the new fast skis to win the Kandahar trophy in 1947 and 1948 (he would win again in 1950). The new skis were dubbed Dynamic K, for Kandahar.

This was the era before the Austrian ski industry had rebuilt from wartime destruction. Top skiers from Austria, including Othmar Schneider, Pepi Stiegler and Anderl Molterer used the K at the Oslo Olympics in 1952. The ranks of Dynamic K medalists included Andrea Mead Lawrence.

There were more innovations: an adjustable-flex ski (it worked, but was heavy and expensive), steel tail protectors with rubber bumpers, continually improved Cellolix formulas. By the late 1950s, Dynamic race skis were available with polyethylene bases. Slalom specialists asked for a lighter, livelier ski, so Michal came up with core laminations of softer wood to produce the Slalom Léger (light slalom). By 1960, Guy Perillat, Charles Bozon, Francois Bonlieu and Michel Arpin were winning races on it.

Meanwhile, Claude Joseph contacted Michal for help in creating a fiberglass ski. Joseph manufactured glass-reinforced polyester panels, mainly as roofing. By 1962, Michal and his team, which included the slalom champion Charles Bozon, had figured out how to wrap fiberglass and polyester resin around a laminated-ash core to produce the Compound RG5 slalom ski (RG stands for Resin-Glass). At the 1964 Olympics, Christine and Marielle Goitschel won slalom gold and silver on the RG5, and Francois Bonlieu won slalom gold. As far as we know, these are the first Olympic medals won on fiberglass skis—skis built in Sillans, according to Jean Michal.

Claude Joseph claimed otherwise. According to him, the RG5 competition skis were made at an efficient new factory in Sallanches, just downvalley from Chamonix. There Joseph, in partnership with the metal-working company Ressorts du Nord, had a new joint venture called Aluflex, after the aluminum skis Joseph had licensed from the American firm TEY. Aluflex had hired James Couttet and were working hard to seduce Chamonix instructors and patrollers away from Dynamic and Rossignol. In the course of time, the new company would become Dynastar, in imitation of Dynamic.

Once it became clear that Joseph was using Dynamic technology to compete with Dynamic, Michal severed their development contract and quit making the RG5. Instead, Michel Arpin rushed into production with the VR7 (verre resine, seven years in testing) and pushed forward with the VR17 (Charles Bozon was killed in an avalanche in the summer of 1964.)

The VR17 improved on the RG5/VR7 technology in several ways. Based on input from Jean-Claude Killy and his team-mates, the VR17 was molded with epoxy, harder and much tougher than polyester resin. It used another new invention, developed by Bernard Fouillet in conversations with Berthet from Tissmetal: the elastic edge (in North America, we call it the cracked edge). By taking the stiffness and springiness of the steel edge out of the ski flex equation, Bozon and Arpin were able to use thicker layers of glass, improving the torsional stiffness and vibration-damping. The result, introduced in 1965, was an ice-skate on hard snow. The ski won Olympic medals in 1968, 1972 and 1976; until the advent of shaped skis, the VR17 was the pattern for almost every successful slalom ski from factories around the world.

Following Paul Michal’s retirement, the book follows its author’s own career managing Skis Dynamic, and the firm’s gradual dismemberment following its sale in 1971.

Une Histoire des Skis Dynamic, by Jean Michal. 2022, Books on Demand (info@bod.fr). E-book €12, print €25 at fnac.com/a17536645