How concern for the national health and military preparedness led France to build the infrastructure for Chamonix, 1924.

By E. John B. Allen

The generation of men and women who took to recreational skiing on the Continent prior to the World War I looked to Scandinavia as the fount of all things skiing, northern countries with a five-thousand-year head start in utilitarian and sporting activities. The Continent’s military noted the effectiveness of Norwegian ski troops and eventually emulated the notion, Russian, German, Austrian, Swiss and Italian regiments were experimenting with ski troops in the 1890s. The English were contemplating training ski soldiers to guard India’s Himalayan frontier.

The French soon followed. Toward the close of the 1800s, Italian-French border relations had taken on a wary unease. The Revue Alpine of 1901 noted that France and Italy had designated frontier zones in which civilians were not allowed. It was natural then that French military officers stationed in the alpine forts had begun by 1891 to consider using ski troops to patrol the alpine border.

Four French officers made attempts to introduce skis to the military: Lieutenants Widmann, Monnier and Thouverez, and Captain Francois Clerc. Widmann was Swedish, Monnier had skied in Norway, Thouverez was with France’s 93rd Mountain Artillery, and Clerc commanded a company in the 159th Infantry Regiment. These four wrote to the French Ministry of War, prodding them toward establishing ski troop detachments.

The major obstacle to the idea was the general ill health of the French mountain people—the population habituated to the altitude and climate from which the crucial recruits must necessarily be drawn. French villagers of the time survived in primitive and unsanitary conditions that were especially deleterious in winter. Tuberculosis and influenza were rampant, along with the afflictions of goiter and rickets. The romantic patina often applied by writers of village life in the Alps before the intrusion of tourism and urbanization ignored the struggle for survival against disease, malnourishment and unsanitary conditions that were endemic a century ago.

The health problems were acute enough that governmental efforts to improve them took on a note of urgency. In 1902 the French Assembly passed a public health law. How it was carried out depended on the efficiency of each region’s Hygiene Council. In Grenoble, for example, the Isère council took up anti-tuberculosis measures right away according to the 1902 archives of the Grenoble Counseil d’Hygène. Problems with drinking water and sewage disposal continued, however, until addressed in 1908.

A French law of April 15, 1910 gave to the high altitude, climatic stations the right to charge vacationers a residence tax under the condition that certain hygienic conditions be guaranteed, a closed sewer system, etc. These rules were modified and finally set down by France’s Academy of Physicians in May 1913.

Both French national and regional governments were also deeply desirous of supporting and maintaining the growth of mountain tourism. Government health initiatives were driven increasingly by economic as well as military and public health considerations. The steep growth of winter sports devotees early in the 1900s occasioned sharp scrutiny during the winter months by local health commissioners. A not inconsiderable amount of money was at stake. The fortress town of Briançon, for example, hosted 50,000 visitors in 1909, a figure that rose to 65,000 by 1911, according to La Montagne, the publication of the Club Alpin Francais (French Alpine Club, or CAF). Mountain tourism was growing to the extent that huts owned by the French Alpine Club were being replaced here and there by small hotels catering to sportsmen.

There was also a second growing stream of city people who came for “the cure,” a better chance to recover from tuberculosis or influenza. Allotte de Fuye, an early alpinist-skier, wrote in 1891, “Doctors will very quickly understand…that influenza cases…should be sent fleeing from the pestilential centers to breathe the revivifying air…with no trace of microbes.”

There were no flu vaccinations in that day. In the next quarter century, the flu mercilessly wiped out a hundred million people around the world in recurrent epidemics. In the West, more individuals died as a result of the 1918 flu epidemic than were killed in World War I to that point. People paid great attention to scientific studies promising a healthier environment at higher altitudes. A report in the 1884 Annuaire de l’Oservatoire showed that a cubic decimeter of air could have a widely-varying bacteria count: 55,000 in the Rue de Rivoli, Paris; 600 in a Paris hotel room; 25 at 560 meters altitude in the French Alps and 0 at 2,000 to 4,000 meters. Clearly, such studies supported the belief in the healing and hygienic advantages of health-cum-sporting stations.

The health problems of the mountain population had to be dealt with, first and foremost. Along with disease, alcoholism was frequently given as a reason for their ill health. But alcoholism was probably not a problem on a level with that of winter living conditions. Maintaining sufficient warmth to sleep comfortably, in the context of sparsely available firewood forced the villagers to use body warmth of their domestic animals. Mountain farmers simply moved above their stables from December to April. The degeneration of the mountain population, Clerc wrote, “is not due to alcoholism…but to the fashion of living in winter.” The captain had recruited in these villages, had gone into “these dens [where] one cannot breathe after a few minutes.”

“Five months stable living,” commented another observer of winter conditions in the French alpine villages. Val d’Isère was Val Misère: “snow, always snow, then snow again and after three days no hope; the beasts are shut up for six months. For a month now the snow has kept us in our houses and all work stops. We await March and April,” was the summation appearing in the 1903-04 Revue Alpine.

Malnourishment was also severe. In 1905, Captain Clerc noted that “in certain high villages…one is unhappily impressed by the rickets of the race. In five male births, one has trouble in a few cantons to find a [20-year-old] fit for service.” A survey by the military showed that a great number of conscripts from mountain villages had failed to grow to a mature height of more than five feet. Another result of poor diet was that four per cent of the population of mountainous Savoy, long known as “the fortress of goiterism,” suffered from the affliction. Recruits at the Briançon garrison were taken to see the unfortunates, “emblems of beauty,” as one wrote on a postcard home.

The immediate military threat from Germany became stronger toward the close of the 1800s. With the defeat of 1870-71 always in mind, the national need for a pool of youth strong enough to withstand warfare both in summer and in winter spurred the French to found a number of sporting associations to promote healthy, athletic pursuits for youngsters. The Ferry laws of 1881 made military exercises compulsory in schools and may have given the impetus to the burgeoning number of sports clubs engaged in shooting, gymnastics, running and swimming. Although a report from the Jura noted that, while there were 105 shooting clubs in the region compared to eight ski clubs, skiing nevertheless became part of this movement to combine sport, morality, health and patriotism.

The Cercle de gymnase de Serres was founded in 1876 for “honest recreation and to encourage sentiments of virtue, fraternity and patriotism.” In Gap, Les Etoiles des Alpes was founded in 1884 “to give youth a civic education as preparation for military service.” One sports organization published a statement in 1911 stressing development of the “physical and moral forces of the young, [to] prepare in the countryside robust men and valiant soldiers and create among them friendship and solidarity.”

This is exactly what the French Alpine Club implied in its motto Pour la Patrie par la Montagne. Its leadership sought to persuade mountain villagers that skiing was not just some wealthy acrobatic sideshow. The French Alpine Club’s Winter Sports Commission, created in 1906, was given official charge of French skiing a year later on the condition that the commission recognize the importance of “skiing’s patriotic and military importance and, its moralizing force as a sport.”

The sentiment was based on the belief that, at the turn of the 20th century, the Norwegians had taken to skiing “as part of their regeneration” during their bloodless but acrimonious and bitter struggle for independence from Sweden. Thanks to a general belief that physical exertion could halt the degeneration of the French mountain people, skiing was transformed from a pastime of the adventurous and wealthy into a means to ensure “strong men and strong soldiers.” Herein lay the true purpose of what was billed as CAF’s first Winter Sports Week, yet the diplomas were for a Concours International de Ski. It was held at Mont Genèvre, near Briançon on February 9-13, 1907. Designed as propaganda for military preparedness, it also had the effect of bringing skiing to civilian notice. The French Alpine Club and the French military both pushed skiing as a means to “better the nation’s defense at the same time as bettering the alpine population.” Both Clerc and subsequent commanders at Brançon, Captains Rivas and Bernard, encouraged soldiers who had received ski training during their periods of military service to return to their villages and teach children to ski. This would drag the villagers out of their winter hibernation and ensure a supply of able ski troop recruits. Rivas, for example wrote in 1906 that he was delighted that 15 out of 18 demobilized servicemen were making skis in their own villages that year.

The French Alpine Club made skiing as a patriotic fitness crusade. “The amelioration of the race haunted us,” wrote Henry Cuënot, the leading CAF spokesman as president of its Winter Sports Commission, looking back at the club’s early efforts to promote the sport. “One knew that Norwegians took to skiing as part of their regeneration, one understood its patriotic and military reach. One wanted to make strong men and strong soldiers.”

The French Alpine Club undertook to organize annual international ski meets, beginning with the one in 1907 at Mont Genèvre near Briançon. From the first, these ski meets ranked as major national sporting events covered by a large number of French papers. There were reporters from L’Illustration, L’Auto, Armée et Marine, Le Petit Parisien, Les Alpes Pittoresques—to name five of twelve newspapers represented at Mont Genèvre. Visiting foreigners brought the excitement of international competition with the Italian Alpini providing a special dash. At Genèvre there was an ice Arc de Triomphe. On one side was CAF’s motto, Pour la Patrie par la Montagne (For the Fatherland by way of the Mountains), on the other was L’Amour de la Montagne abaisse les Frontières (Love of Mountains does away with Frontiers). Patently, skiing was part of the Franco-Italian détente. CAF held its second meet in 1908 at Chamonix. The third in 1909 was at Morez in the Jura. CAF’s letter soliciting prizes for the Morez meet was clear in its meaning: “Our context is the most powerful means of spreading in our country, a sport which regenerated the Norwegian race.” And Norwegians were always present, adding their supreme authority to the competitions.

The theme of regeneration runs through club discussions and reports. Henry Cuënot, the spokesman for regeneration, wrote many of CAF’s notices. The military fully supported the annual meets by providing a band, teams of soldiers, and the patronage of any number of high-ranking officers. These patrons, if they did not attend themselves, sent deputies to speak the right words at the award banquets. At the 1908 meet, General Soyer, filling in for General Gallieni (who had been at the meet the previous year), affirmed that “all mountain sports are incomparable in making men valiant and vigorous.”

The fourth CAF meet was held in 1910 at Eaux Bonnes and Cauterets and the fifth, the following year, at Lloran. It was CAF’s policy to hold the meets all over snow-covered France. By the time the seventh annual meet rolled around, correspondents from 17 papers covered the event held in the Vosges at Gérardmer in 1914, and was the occasion of the awarding of the first military Brévet for skiers. Successful candidates won the right to choose which ski regiment they would join when called to the colors, which happened all too soon; August 1914 the tocsin sounded for World War I.

But Chamonix was coming into its own during those years. It was not the mountains that had first attracted men to the Chamonix valley, but its glaciers. In the enlightened 18th century had come the Englishmen Windham and Pocock, the first of a long line of gentlemanly amateurs. Mt. Blanc was climbed in 1786. In the Romantic age, the high lakes were the attraction, and only from about the mid-19th century did alpinism take hold. There was much foreign business prior to skiing in the valley. In 1860 Chamonix welcomed 9,020 visitors, in 1865 the number was up to 11,789, with the English supplying about one third. Chamonix became “a little London of the High Alps” in the summer season. In 1860 there were 7 hotels, 10 in 1865 including the 300-bed Grand Imperial. An English church was built in 1860, the telegraph arrived two years later, the first of the mountain huts, the Cabane des Grands-Mulets was ready in 1864, and Whymper climbed the first ‘needle’ in June 1865. Skiing came in 1898. Arnold Lunn remembered the guide “who regarded his skis with obvious distaste and terror. He slid down a gentle slope leaning on his stick, and breathing heavily, while we gasped our admiration for his courage.” Chamonix skiing prospered thanks to the local GP, Dr. Payot, who took to visiting his patients on skis. By the beginning of the 1907-08 season there were about 500 pairs of skis in town. CAF was mightily pleased with its propaganda, for skiing was “social and patriotic at the same time.” Chamonix was CAF’s choice for its Second International Week in January 1908. Two hotels had remained open for the winter of 1902, four in 1906, and the number tripled by 1908. The hoteliers had been skeptical at first of CAF’s enthusiasm, but had joined in as the day grew closer. They ended up “surprised by the affluence of their visitors” whose choice was for hotels with central heat. Heating was a major concern for villages and towns as they started to attract winter visitors.

The meet was a resounding success. The reception for the alpine troops, the gentry in their sledge carriages made a fine show, baby carriages on runners provided a charm and calm to the physical presence of all the skiers, the lugers, and bobsled teams. The sober colors of the skiers’ clothes mingled with the elegant costumes of the ladies. Officers from Norway, troops from Switzerland and of course, France’s own Chasseurs Alpins were the cynosure of all. The throng included amateurs from home and abroad, and guides and porters busied themselves throughout the town: all under a radiantly blue sky with the Mt. Blanc chain creating a magnificent backdrop, “a picture rarely seen and suggestive to a high degree.” Chamonix had become Chamonix-Mt. Blanc, a “new winter station…equal to the big Swiss centers,” enthused one commentator in the Revue Alpine.

A new winter station? Maybe. Certainly one not to equal those in Switzerland, nor, indeed, could it compare with its status as a summer destination. In the summer of 1907, Chamonix welcomed approximately 2,000 visitors a day, for a total of c. 170,000. A little more than 2,000 had been in town for its winter week. It was a start to Chamonix’ becoming France’s premier ski and winter sports station, even if it could not compete with St. Moritz and Davos.

Although the numbers of visitors did not greatly increase during the winter seasons—11,725 in 1911-12 to l2,975 in 1912-13—Chamonix’ standing as premier in the places to ski was enhanced by CAF’s sixth international competition in 1912. Of course there was commentary in the French papers, but it also received notice in Oslo’s Aftenposten and in the Italian paper, Lettura Sportiva. Excelsior, a French paper, put it exactly right, just what CAF wanted to hear: “Chamonix shows, this year, as in others, that it knows how to organize sporting events.”

Chamonix capitalized on its renown and started major advertising abroad. “Sunshine is Life” read an advertisement cued to the fogged in English in 1913. Cheap 15-day excursion return tickets from London cost just £4.0.3 in 1913.The following year the town’s tourism committee decided to spend some of its advertising budget on Algerian and Tunisian newspapers. As the war loomed, Chamonix was thinking internationally.

During this pre-war period, skiing also spread throughout the local community. Much of the early enthusiasm was generated by Dr. Payot. He made the Col de Balme on February 12, 1912 and followed it by crossing the Col du Géant to Courmeyeur in 14 hours two weeks later. The following season he did the traverse Chamonix to Zermatt. He not only was an ardent apostle for skiing, but also for its physical benefits. Skiing was seen as liberating Chamonix folk from the servitude of the snow, bringing health and renewal. As Payot wrote in 1907 in La Montagne, Chamonix residents of all ages were taking to the sport enthusiastically. It was life in the open air. It was impossible, wrote Payot, “when one has got the blood going and the lungs full of pure air to endure the nauseous atmosphere of double-windowed houses.” It was the end of anemia by confinement. Living was being aerated and sun-drenched, and this, better than thirty ministerial changes in the government, would bring both moral and physical benefits.

It was to youngsters, though, that the French government leadership looked, “impetuous and fecund youth which is little by little declining; they all come to ask of the sun and the pure air power for the days to come or the courage to replace what the days past have extinguished.” There was a strain of romantic desperation sounded as the ominous possibilities of armed conflict between France and Germany turned to probabilities on the eve of World War I. Pour la Patrie per la Montagne took on new significance in the years leading up to the declaration of war in 1914. The French Alpine Club organized L’Oeuvre de la Planche de Salut to provide free skis for mountain children. Few would miss the double meaning of Planche de Salut—these skis were not merely healthy boards but they were also boards of last resort, as one might throw out to a drowning swimmer. In a few years the children “will make a marvelous army of skiers perfectly trained and ready to defend the soil of the fatherland if needed.”

“Today,” wrote one of the very few critics of the idea of mingling the ideals of sport and war, “it is not only correct but elegant to be patriotic. The wealthy…add snobbism to their personal pleasure in the aid of national defense, even of the regeneration of the race.”

But a patriotic attitude rather than irony held sway generally. The enthusiasm for fitness manifest in the French Alps, was echoed equally in the Jura, where the earliest sports organization was the “Vélo-Club,” founded in 1892, followed by the “Union Athlétique Morézienne” whose manifesto referred to skiing as “an excellent means of social hygiene.” The sick and the tourists came to the little towns of the Jura “to find repose and health in the mountains and the forests of fir.”

As proclaimed in Savoy, the French needed regenerating because of the squalid conditions of the cities. “Alcoholism, venereal disease and tuberculosis continue death’s work,” was one Savoy doctor’s summation in 1906.

The “air cure,” especially for weak children, was promoted in Chamonix. There puny mites were being turned into robust little fellows by sport and sun well prior to the onset of the Great War. Chamonix’ Dr. Servettaz claimed he required only two months to make children “stronger, with larger chests and lungs, muscles more solid and dense, blood more rich.” Chamonix’s high altitude was widely credited with increasing appetite as well as being good for sleeping.

A Mirroir article in 1914 carried a photo of tracks leading straight to a snowy peak with the skier victorious on top. The caption praised the true alpinist who forgoes the easy pleasures of luge and skeleton and who “with will power, courage, endurance, a strong heart, and fighting white vertigo, specializes in great ascents.” These physical and mental attributes, it was widely believed, would carry Frenchmen to victory in the oncoming battles of World War I. In the midst of the war, the French Alpine Club publicly speculated that one possible positive aspect of the war was that it would exercise a happy influence on general health. Whether it did is immeasurable.

Still, the Ministry of War in 1920, two years after the Armistice had been signed, recognized the French Alpine Club as the organization promoting “physical instruction and preparation for military service” by giving CAF a ten-thousand franc subsidy. Tourism and national health, however, had by then become of more immediate concern than military preparedness. France was urged “to win the peace.” The National Tourist Office, the Ministry of War, the French railroad companies, and syndicats d’initiative all involved themselves deeply in the “future of tourism in France and the development of the race by the cult of sport.”

After the war as well, France’s mountain communities turned the number one national health problem to advantage. In the generation before the advent of antibiotics, tuberculosis killed off French citizens by the tens of thousands. In 1926, it was responsible for some 20% of all French deaths—almost 150,000. Since the only known effective cure was to dwell for considerable length of time in cold, clear mountain air, mountain villages began to bloom with “cure hotels” for tuberculosis patients. The extensive services required by the sanitariums busied villagers profitably in supplying the services required.

The tuberculosis bonanza, paradoxically, could have driven off healthy tourists. The French government, to meet this threat, distributed subsidies to the mountain villages agreeing to stringent conditions for hoteliers in order to separate patients and tourists. In Mégève, for example, all visitors in 1932 had to present a doctor’s certificate, attesting that they were free of the contagion.

The village of Passy went at the problem by dividing itself into two zones: between 1,000 and 1,400 meters, “cure hotels” and pensions catering to the tubercular received guests under medical supervision. The sick were barred from the second zone, within the village itself. As a result of the quarantine approach, tourists continued to come. In the twenty-five years between 1914 and 1939, Mégève grew from a village with three hotels to a town with 66 hotels—from 140 beds to 2,400.

Enter the Olympic presence: Winter Olympics had been contemplated since 1899 but had always run up against Sweden’s Colonel Balck, the promoter of the Nordiska Spelen. His friend, Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic Games and president of the International Olympic Committee, was not especially noted for his keen interest in skiing. He had been impressed with Balck’s Games (particularly the military skijoring races) run every four years, and did not give much thought to trying to incorporate skiing into the Olympic program, in spite of what he said at Chamonix in 1924. He believed, in 1908, that skiing had a “hygienic value of the highest order” and called it “the best medicine for tuberculosis and neurasthenia.” However, he was often invited to join the Honorary Committee of CAF’s meets.

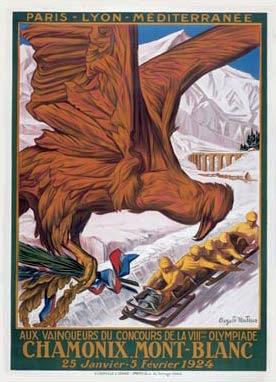

After the war, Chamonix was also growing apace in the twin categories of health center and ski station, particularly the latter. It developed the best lifts and the most expert terrain and was, in that sense, the country’s most prestigious ski village. Chamonix in particular and the French in general had acquired an infrastructure and the experience needed to host ever larger winter competitions—both accumulated beginning in the prewar governmental programs concerned with health, war and tourism. The climax of all this effort came in 1924 when Chamonix was chosen as the site of what became in retrospect authorized as the First Winter Olympic Games. It had not been easy. The Scandinavians had opposed joining the Olympics for years. Coubertin was never an advocate and in 1920 believed that “les sports d’hiver sont douteux,” (winter sports are doubtful) as he penciled in on one protocol. The IOC felt increasing pressure to award the 1924 Games to France, “victor and martyr” of World War I. CAF threw its weighty support behind the proposals for winter games. Meanwhile the Scandinavians sent a warning to the IOC that if skiing were included, they would not attend. At its meeting in Lausanne in 1922, the IOC decided that there would be Games under its patronage but they were not to be thought of as “Olympic” and “champions had no right to medals.” The Games, then, were to be considered as merely an extension of CAF’s International Sporting Weeks that had begun at Mont Genèvre in 1907. The Scandinavians did not approve of this but went along with the contract signed with Chamonix (Gérardmer and Superbagnières were mildly considered) on February 20, 1923 since they were assured that they would not be Olympic Games. “It is absolutely essential,” wrote Siegfrid Edström, the Swedish President of the IOC to the French representative Baron W. de Clary, “that the Winter Games do not take on the character of the Olympic Games,” but to characterize them as “international” would ensure Norwegian, Swedish and Finnish participation.” All parties involved kept this international, as opposed to Olympic, front while the Games were in preparation. The Winter Sports Week was “not an integral part of the Olympic Games,” confirmed Fratz-Reichel, the Secretary of the Committee overseeing the plans and installations at Chamonix. As the opening of the Games drew closer, the difference between an international sports week and a Winter Olympic Games became increasingly blurred, even in the Executive Committee of the IOC. In effect, France’s immense turn-of-the-20th century concern with the deteriorating health of its mountain villagers, its efforts to create a healthy population for military preparedness in the first instance, and a desire for profitable mountain tourism as a second priority led to a much grander concept. The mounting of ever more grand ski tournaments readied France in general and Chamonix in particular to produce what amounted to the First Winter Olympics, retrospectively granted that status by the IOC in 1925.

After the war, Chamonix was also growing apace in the twin categories of health center and ski station, particularly the latter. It developed the best lifts and the most expert terrain and was, in that sense, the country’s most prestigious ski village. Chamonix in particular and the French in general had acquired an infrastructure and the experience needed to host ever larger winter competitions—both accumulated beginning in the prewar governmental programs concerned with health, war and tourism. The climax of all this effort came in 1924 when Chamonix was chosen as the site of what became in retrospect authorized as the First Winter Olympic Games. It had not been easy. The Scandinavians had opposed joining the Olympics for years. Coubertin was never an advocate and in 1920 believed that “les sports d’hiver sont douteux,” (winter sports are doubtful) as he penciled in on one protocol. The IOC felt increasing pressure to award the 1924 Games to France, “victor and martyr” of World War I. CAF threw its weighty support behind the proposals for winter games. Meanwhile the Scandinavians sent a warning to the IOC that if skiing were included, they would not attend. At its meeting in Lausanne in 1922, the IOC decided that there would be Games under its patronage but they were not to be thought of as “Olympic” and “champions had no right to medals.” The Games, then, were to be considered as merely an extension of CAF’s International Sporting Weeks that had begun at Mont Genèvre in 1907. The Scandinavians did not approve of this but went along with the contract signed with Chamonix (Gérardmer and Superbagnières were mildly considered) on February 20, 1923 since they were assured that they would not be Olympic Games. “It is absolutely essential,” wrote Siegfrid Edström, the Swedish President of the IOC to the French representative Baron W. de Clary, “that the Winter Games do not take on the character of the Olympic Games,” but to characterize them as “international” would ensure Norwegian, Swedish and Finnish participation.” All parties involved kept this international, as opposed to Olympic, front while the Games were in preparation. The Winter Sports Week was “not an integral part of the Olympic Games,” confirmed Fratz-Reichel, the Secretary of the Committee overseeing the plans and installations at Chamonix. As the opening of the Games drew closer, the difference between an international sports week and a Winter Olympic Games became increasingly blurred, even in the Executive Committee of the IOC. In effect, France’s immense turn-of-the-20th century concern with the deteriorating health of its mountain villagers, its efforts to create a healthy population for military preparedness in the first instance, and a desire for profitable mountain tourism as a second priority led to a much grander concept. The mounting of ever more grand ski tournaments readied France in general and Chamonix in particular to produce what amounted to the First Winter Olympics, retrospectively granted that status by the IOC in 1925.

The uneasy beginnings of Winter Olympics at Chamonix continued to plague the Games in 1928. The Norwegian Ski Association voted 29 for participation, 27 against—hardly a vote of confidence for the Winter Olympics. Not one European had faith that the United States could pull off a successful ski meeting at Lake Placid in 1932. At the end of those ill-attended games, the Technical Committee of the FIS sent a stinging rebuke to Godfrey Dewey. In many ways it was remarkable—considering the politics of the 1930s—that the Winter Games survived the Nazi extravaganza at Garmisch-Partenkirchen in 1936. And then the Second World War put Olympic competition on hold for the duration.

Following the war, the Winter Games increasingly took on a powerful life of its own, particularly after it became fueled by television funding. It is now that huge international undertaking quadrennially riveting the attention of the world’s sports-minded.

The focus has changed drastically. Modern Winter Olympic commentators never hazard the thought that the Winter Olympics are put as a marvelous engine for producing a healthier world population or that these Games constitute fine physical conditioning for potential infantrymen. The theme of the Winter Games (and of the Summer Games as well) has become something altogether different, standing in as a benign substitute for war between nations, a sublimation of future Hiroshimas one hopes will never happen.

Today’s Winter Olympics is an exponentially-growing entity producing ever-larger spectacles for the world’s entertainment, achieving ever-greater complexity within its competitions and attracting ever-larger portions of the world’s attention during those weeks every four years when it is being held on the television screens of the world. In retrospect, it exhibits a wondrously paradoxical contrast to that long-ago series of modest French Alpine Club ski competitions from which those first Winter Games were born three generations ago.