After a stunning comeback this past winter, Lindsey Vonn surpassed Austrian racer Annemarie Moser-Proell’s record number of alpine World Cup wins. Who’s the greatest? The new record ignites a debate that won’t be resolved anytime soon.

Lindsey Vonn on the downhill course at Cortina d'Ampezzo on January 18, 2015. She won the event, tying Annemarie Moser-Proell's record. The next day, Vonn won the Super G. Photo By Agence Zoom / Christophe Pallot.

By Edith Thys Morgan

When Lindsey Vonn crossed the Super G finish line in Cortina for her 63rd World Cup win on January 19, she knocked Annemarie Moser-Proell off the top step of the podium for total World Cup wins. At press time in early March, she had racked up two more first-place finishes for 65 and counting.

But these landmark victories did nothing to answer this question: Who’s the greatest all-time skier in the history of women’s World Cup racing? For those who measure such things, Vonn’s record-setting win only fanned the flame of a discussion that won’t be resolved anytime soon.

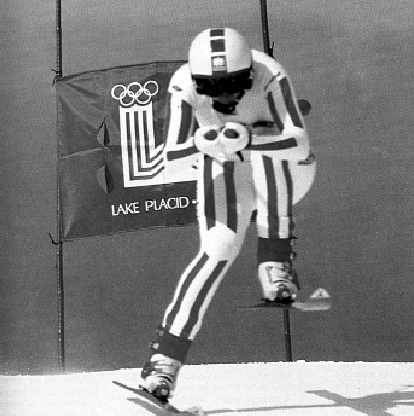

Proell charges toward DH gold at the 1980 Winter Olympics. Photo Courtesy of International Olympic Committee

Proell charges toward DH gold at the 1980 Winter Olympics. Photo Courtesy of International Olympic CommitteeA dominant champion and colorful character on the women’s tour from 1970 to 1980, Moser-Proell clinched five World Championship titles as well as the 1980 Olympic downhill gold at Lake Placid. During her best years, she scored victories in all disciplines during the same winter — and from 1972 to 1974 notched eleven consecutive downhill victories. She retired in March 1980, with 62 wins, after 11 seasons on the World Cup tour.

Those who favor Moser-Proell, despite Vonn’s record-breaking feat, point to three factors that garner her the top spot: winning percentage, overall titles and the Super G. Vonn competed in 332 races to claim her record, while Moser Proell took a mere 174, a winning percentage of 19 and 35 percent, respectively. As for overall titles, Vonn is two behind Moser-Proell’s tally of six — but she came crushingly close to matching Moser-Proell’s five consecutive titles (1971–75) in 2011, when she lost what would have been her fourth consecutive title by a mere three points to her closest friend and rival, Maria Hoefl Riesch. Vonn won her fourth overall title the following year.

INTERNATIONAL DEBUT

Probably the biggest single point of contention is the Super G factor. Both Vonn and Moser-Proell won in all events available to them at the time. Both excelled at speed events, but Moser-Proell’s dominance included GS. The addition of Super G to the World Cup schedule in 1982–83 offered many more events that favored speed skiers, and indeed, 22 of Vonn’s victories were in Super G. As Cindy Nelson points out, there is no question that Moser Proell would have excelled at the event: “She had Tamara (McKinney) feel with Lindsey size, and was best on rolling terrain when she could accelerate. She would have been incredible at Super G.”

During the shorter span of her career, Moser-Proell was the singular dominant force in women’s skiing. Vonn’s success over eleven years (2004–2015), which included intermittent streaks of dominance in the speed events, is more aptly defined by her dogged persistence, comebacks and longevity, all of which continue to impress. Both transcended the ski world to become legends in their own countries. For Moser-Proell in ski-crazy Austria, that meant elevating herself above the male ski heroes of the day—working, playing and winning at their level and beyond. For Vonn, it meant breaking into the mainstream consciousness in a country that knows and cares little about alpine skiing. It meant capturing and then enduring the white-hot glare of media attention during the most emotionally vulnerable part of her career, and ultimately winning the respect of skeptics and detractors.

Each in her own day set a new standard among her peers. At the very least, before making any proclamations one needs to look at their paths and understand their respective eras. Here is a closer look at how Vonn and Moser-Proell each achieved 60-plus wins.

FIRST TURNS

Lindsey Caroline Kildow, born in 1984, learned to ski at age two and was soon thereafter training nightly at Buck Hill in Minnesota under the tutelage of her highly competitive father, Alan, and renowned ski coach Erich Sailer. She moved with her mother to a condo in Vail at age 11, and ultimately the entire family, including four siblings, followed so that she could devote herself to ski training. Right away, coaches at Vail were impressed by her technical mastery and introduced her to speed events, in which she rapidly excelled. By age 11 she was skiing year-round, and by 12 was sponsored by Rossignol, the same ski brand used by her early role model Picabo Street.

Annemarie Proell, born in 1953 as the sixth of eight children, lived in her parents’ farmhouse several hundred meters above the tiny village of Kleinarl, Austria. She started skiing at age four on homemade skis and was the first of her family to ski race. (Her sister Evi had a brief World Cup career.) Her parents, despite being Austrian, had “Keine Ahnung” (“no clue”) about ski racing and could provide neither ski clothes nor good equipment. The local priest recommended her to the regional ski association. After winning her first local championship at age 13, she wrote a letter to a ski company asking for equipment and was denied.

At age 14, Vonn and teammate Will McDonald became the first Americans to win the Tropheo Topolino youth competition in Italy. At age 15, Vonn started traveling with the U.S. Ski Team and was by then doing her studies on the road through the University of Missouri Online. She raced her first World Cup in 2000 at age 17. Her first podium came at Cortina in 2004, in her 46th World Cup race. Her first win came on December 3, 2004 at age 20. By that age, Moser-Proell had 27 wins and three overall World Cup titles under her belt.

Moser-Proell made her World Cup debut in 1968 at age 14 (then the minimum age to race FIS), falling three times and finishing last at Badgastein. She joined the Austrian Ski Team the following season under the direction of coaching legend Charly Kahr. Her first podium came that January, at age 15 in Saint Gervais, with a second place in downhill. She won her first race, a GS at Maribor, the following season, at age 16, and also captured bronze in giant slalom at the 1970 FIS World Alpine Championships at Val Gardena. At age 17 she won her first downhill World Cup race, and clinched the first of six overall titles in Are, Sweden. Her seven victories that season included all three disciplines on the World Cup at that time—downhill, slalom and (one-run) giant slalom.

HARD KNOCKS

Beyond her skills and competitive drive, coaches remember Vonn’s frequent hard crashes, big high-speed yard sales from which she typically walked away. Her first time in the spotlight was her body-wrenching crash in training at Sansicario during the 2006 Torino Olympics. Despite hospitalization she returned to race, finishing 8th.

The longevity of her career is thanks in part to enhanced safety in ski racing venues. The frozen hay bales and picket fences that lined World Cup courses in the 1970s have been replaced with the highly effective A and B netting that line today’s venues. Moser-Proell steered clear of the hay bales by being a canny competitor, keeping her own line secret during inspection, and even skiing off course during a training run to observe and find the perfect line.

Vonn pops a champagne cork after she won her record- breaking 63rd World Cup race in Cortina in January 2015. Agence Zoom / Christophe Pallot

Vonn pops a champagne cork after she won her record- breaking 63rd World Cup race in Cortina in January 2015. Agence Zoom / Christophe PallotWELL-ROUNDED

Both Vonn and Moser-Proell won in all disciplines available to them — four for Moser-Proell and five for Vonn. It took Vonn 11 seasons to win her first GS, of only three total. Moser-Proell’s GS was nearly as strong as her DH, and she notched 16 wins in that event. Vonn and Moser-Proell share a relative weakness in slalom, with two and three wins respectively. Both were up against specialists in their day, though with more races in the modern World Cup schedule (17-29 races per year during Moser-Proell’s reign, versus 33-38 during Vonn’s), the task for all-arounders to manage the training, rest and gear required to compete in five distinctly contested events (versus three in Moser-Proell’s era) is considerably more challenging.

EXPERIENCE COUNTS

Vonn has won on the Lake Louise course 14 times. Moser-Proell’s most wins came at Pfronten, which she won seven times, including her last World Cup downhill in January 1980 — the only speed event missed that season by her archrival, Switzerland’s Marie-Theres Nadig. With the tour returning to classic courses annually, as it has in Vonn’s entire career, experience becomes a compounding advantage. During Moser-Proell’s reign, some of the classic downhills on the tour were not run every year, and racers did not ski the hill for Super G as well, giving experienced racers less of a relative advantage. On the flip side, all racers and especially women retired much younger during Moser-Proell’s era, so she did not have to maintain her dominance through multiple waves of young, fresh stars as Vonn has.

GETTING PHYSICAL

Vonn was not athletically gifted in her early years; she was a tall skinny girl and self-described klutz who came into her strength late. That shifted when her father hired a strength coach from the San Francisco 49ers and exploded when she signed with Red Bull in 2005 and became part of their Athletes Special Projects, run by former Austrian downhill trainer Robert Trenkwalder. Per Lundstam, a trainer for the U.S. Ski Team from 1994–2010 and now with Red Bull recalls: “Once she got it into her head to use her physical abilities as a tool she embraced it and thrived.” Vonn, at 5’ 10” and 165 pounds, simply out trains the competition, with high-volume workouts and the most advanced sports science and facilities in Austria and at home.

Moser-Proell also started out as skinny girl who grew mighty in stature. While Vonn’s strength is built through methodical process in the gym, Moser-Proell’s came first from necessity (working on the farm and climbing home after school). Though never known for her athleticism, she skied herself into shape and used the après ski-loving, work hard/play hard image to underscore her overwhelming strength.

OLYMPIC TRIALS

After an impressive sixth place in combined (the best U.S. result for the women’s team) in her Olympic debut at the 2002 Games at Salt Lake City, Vonn came into 2006 as a top U.S. medal contender in the speed events. However, teammate Julia Mancuso stole the show with a gold medal in the GS. Moser-Proell was also upstaged in her first Olympics in 1972. Even as the Austrian team threatened to pull out of the Olympics following Karl Schranz’s ban, Moser-Proell was the clear favorite in both the DH and GS. But Switzerland’s Nadig won gold in both events. Both Moser-Proell and Vonn sat out an Olympics at the peak of their careers — Vonn in 2014 and Moser-Proell in 1976.

Moser-Proell celebrates her downhill gold at Lake Placid. She retired from racing soon after the 1980 Winter Games. Photo courtesy of International Olympic Committee

Moser-Proell celebrates her downhill gold at Lake Placid. She retired from racing soon after the 1980 Winter Games. Photo courtesy of International Olympic CommitteePOINTS

The current scoring system, where race points are awarded to the top 30 finishers, starting at 100 for a win, was implemented in the 1991–92 season. In Moser-Proell’s era, 25 points were awarded for a win, and points only went to the top 10. Under the modern scoring method, a consistent racer can amass points even while finishing outside the top 10.

THE COMBINED FACTOR

Moser-Proell's tally is boosted by seven "statistical combined" events that were calculated from separate — and already individually tallied — slalom and downhill races, a so-called “paper race.” Meanwhile, Vonn's five combined victories represented a new, stand-alone event that consisted of one downhill and two slalom runs.

PERSONAL BUSINESS

Lindsey Kildow’s career was first managed by her father Alan and then by her husband, fellow ski racer Thomas Vonn, whom she married in 2007. Thomas became the ultimate “rep,” meticulously managing every detail of her career. The couple divorced in 2011. As author Nathaniel Vinton describes in his 2015 book The Fall Line, the divorce “coincided with Lindsey’s rapprochement with the man who had most opposed the relationship to begin with: her father, Alan Kildow, who threw his energy into the brass-knuckled litigation that lasted more than a year.”

Moser-Proell also established a close racer/rep relationship, marrying her ski technician, Herbert Moser, in 1974. They remained together until his death in 2008.

Vonn has achieved global fame, with red-carpet Hollywood appearances, fashion spreads and magazine covers. She's shown here doing an agility training exercise while shooting an advertisement for UnderArmour in 2011. ASP Red Bull / U.S. Ski Team

Vonn has achieved global fame, with red-carpet Hollywood appearances, fashion spreads and magazine covers. She's shown here doing an agility training exercise while shooting an advertisement for UnderArmour in 2011. ASP Red Bull / U.S. Ski TeamFAME

Vonn embraces the media, particularly after posing for the Sports Illustrated swimsuit edition in February 2010, the year she struck Olympic DH gold in Vancouver. She is featured in ads for everything from Under-Armour to

Alka-Seltzer. Her relationship with golf superstar Tiger Woods has vaulted her into another realm, with red carpet Hollywood appearances, a fashion spread in Vogue, cover stories in People and other U.S. magazines and a year-round media presence. Fame in the United States came much later than in Europe, where she endeared herself to fans by conducting interviews in German. In 2010 she won the Laureus World Sports Awards “Sportswoman of the Year” and captured the Best Female Athlete ESPY in 2010 and 2011.

When Moser-Proell won her first overall World Cup in 1970–71, 10,000 people showed up to celebrate in her hometown. Even today, 35 years after her last victory, Moser-Proell, Austria’s Sportswoman of the Century, is among the most highly regarded and loved athletes in Austria.

Vonn’s global fame, however, eclipses that of Moser-Proell, who was never comfortable speaking to the press in English. Her Cafe Annemarie restaurant at Kleinarl, renamed Café-Restaurant Olympia after she sold it following her husband’s death in 2008, remains a tourist attraction and she appears at major ski events. Though still much loved and revered in her home country, her fame outside of the ski world (she was named a Legend of Honor at Vail in March 2014), does not extend much beyond Austria.

FORTUNE

Vonn’s rewards, in addition to annual multi-millions from contracts with her sponsors, include prize money, which is now awarded at each World Cup race. In 2012, when she won 12 events and the overall title, she topped the list for men and women with $608,000. In 1976 the Olympics laws were rewritten, allowing leniency to athletes who had received money from sponsors, and acknowledging the under-the-table deals common with top European skiers. Though the money exchanged was far less than today, and prize money was not allowed, Moser-Proell’s version of rock-star status included her own technician, a fast Mercedes, and, best of all to the avid hunter, access to private hunting grounds.

IMAGE

Just as Vonn is never interviewed without her Red Bull hat on her head or can in her hand, Moser-Proell was closely associated with the cigarettes she enjoyed, whether while partying late at night, or having a smoke just before or after her run. It was at once a ritual of relaxation and of asserting the Alpha role of “La Proell,” as she was called by the French racers and then by international media.

THE COMEBACKS

Both Vonn and Proell took a break at the peak of their careers. Vonn took an involuntary break after her injury in 2013 and the re-injury that kept her out of 2014 Sochi Games. She remained a fixture of the team throughout, but did have to contend with the emergence of a new superstar, teen wonder and Olympic champ Mikaela Shiffrin. Moser-Proell voluntarily retired in 1976, despite the Olympics in her home country, to take care of her ailing father, who passed away later that year. Financial concerns, among other factors, brought her back to the sport the following season, though she was required to requalify for the Austrian team.

ON-SNOW TRAINING

Vonn, like most current World Cup racers, skis year-round on glaciers and in the southern hemisphere during her off-season. Despite the prevailing wisdom of the time (that too much skiing, and training at high altitude, was detrimental), Proell did make the 40-minute drive to Kaprun to take the tram to the Kitzsteinhorn Glacier, which opened for skiing in 1965. Summer skiing allowed Salzburg teams to disrupt the longtime dominance of Tyrol, and led to further glacier skiing developments throughout Austria.

THE GEAR

For contractual reasons, Vonn switched to Head Skis the summer before the 2010 season, inheriting not only Bode Miller’s skis, but his prized technician Heinz Haemmerle. Vonn’s size and strength allowed her to take advantage of the trade-off between the speed offered by longer, stiffer men’s skis versus the maneuverability of shorter women’s skis.

Moser-Proell skied for Atomic throughout her career, living as she did in the village so close to the Atomic factory in Wagrain. However, tensions in Wagrain rose in the fall of 1974 when Proell briefly considered a switch to Kästle. Upon her return in 1976 she signed on with Atomic through 1980. The newspapers reported that she had “$5 million reasons” to come out of retirement, alluding to the money provided by her sponsors Atomic and Dachstein. Moser-Proell’s size, strength and technique allowed her to ski on 225 cm men’s downhill skis as well, though only when the courses and conditions suited them.

Moser-Proell did experiment with a steel plate underfoot, but she preceded the era of Derbyflex and integrated binding plates. Vonn’s racing career started after the development of hinged gates and shaped skis, while Moser-Proell predated both of those changes (hinged gates were fully adopted on the World Cup in 1981 and shaped skis appeared in the Nineties). Vonn is reported to travel with 50 skis. Moser-Proell’s quiver, all carefully selected and tested, included three pairs per event, plus two for freeskiing.

Even today, 35 years after her competitive career, Moser-Proell—named Austria's Sportswoman of the Century—is one of the most highly regarded athletes in the nation. She recently said of Vonn: "Nothing better could happen to skiing…[Lindsey] elevates the sport with her achievements."

Even today, 35 years after her competitive career, Moser-Proell—named Austria's Sportswoman of the Century—is one of the most highly regarded athletes in the nation. She recently said of Vonn: "Nothing better could happen to skiing…[Lindsey] elevates the sport with her achievements."THE LEGACY

Christin Cooper, who won a silver medal in GS in the 1984 Winter Games, makes the case for Moser-Proell being the original skiing feminist, who paved the way for the opportunities, commercial exposure and equal access that racers like Vonn, Lara Gut and Julia Mancuso now enjoy. “Moser-Proell broke new ground in those areas, and only she had the cred at the time to do it,” says Cooper. “She modeled gnarly, unrepentant competitiveness before women athletes had come to own that space with pride and confidence.”

Vonn, in turn, has taken full advantage of what Moser-Proell started and is creating her own legacy in the sport. "She's the best thing that has happened to skiing in a long time," adds 1968 Olympic triple gold medalist Jean-Claude Killy of France. "An unbelievable athlete…and great ambassador for our sport."

Rather than arguing who is better, perhaps it is more fitting to pass the baton from one great champion to the next, as if to say, “It’s your turn, Lindsey. Run with it and see how far you can go.”

Edith Thys Morgan is author of Shut Up and Ski: Shootouts, Wipeouts and Blowouts on the Trail to the Olympic Dream. She raced on the World Cup for six years as a Super G specialist, finishing 9th at the 1988 Winter Olympics.

To read more about Annemarie Moser-Proell, see “Where Are They Now?” in the March-April 2013 issue of Skiing History.

Special thanks to ISHA editorial board member Patrick Lang for contributing to this article; to John Fry, who composed the "Top Ten Women Racers" sidebar; and to Tom Kelly at the U.S. Ski Team and Mo Guile at Agence Zoom for photography.