Short Turns: Skiing and Cycling

Condensed history of a wild marriage.

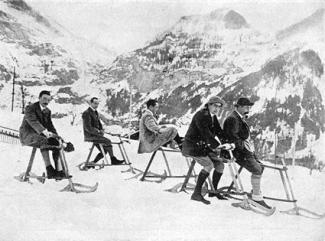

Above: Swiss ski-bobbers in 1913. Courtesy ski-bike.org.

Skiing and cycling have a long history of a symbiotic fit for elite athletes and casual enthusiasts. The two sports sync easily with their alternating seasons and effective cross-training results, along with the same primal thrill of gravity-powered flight. It’s a natural relationship.

The origin story of the bicycle isn’t attributed to any single inventor. An early “wooden horse” could be seen in the 1790s tooling around the Palais Royal in Paris. In 1818, German baron Karl von Drais was awarded a patent on his two-wheel, steerable Velocipede, which has led to him being called the father of the bicycle.

That bicycle DNA took to the slopes in the U.S. in 1892, when the first patent was issued for a skibob. The Ice Velocipede was essentially a converted bicycle—with a steerable ski (or skate blade) in the front, a second ski under the pedals and a studded drive wheel at the rear. It appears, however, that the Ice Velocipede was never manufactured (an 1863 version was a converted penny-farthing high-wheeler).

The first produced versions of the U.S. skibobs were made of wood and included a front ski attached to a steerable bicycle-style handlebar. A second ski was positioned under the seat in a straight line behind the front ski. The rider was outfitted with mini-skis on each foot, equipped with metal claws on the undersides of the tails for braking. They were heavy, clunky and fast, with only the illusion of control once the rider really got moving.

Look and Time magazines wrote about them in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The skibobs also showed up in liquor ads around the same time. Californian William Cartwright tirelessly promoted them and formed the Skibob Club of Santa Rosa in 1965.

Skibobbing remained popular in Europe and had a cameo appearance in the Beatles 1964 movie A Hard Day’s Night. The sport did have its moments in America, including hosting its World Championships in 1971 at Mount Rose, Nevada. But despite endorsements from the likes of Vail co-founder Earl Eaton, interest in skibobbing stalled, with some resorts banning the devices outright. While the United States Skibob Federation dissolved in the mid-’70s, there is now a U.S. Skibob Association (skibobusa.com),and NASTAR has a skibob division.

Also in the 1970s, early versions of mountain bikes first appeared in Crested Butte, Colorado, and Mill Valley, California, and soon became a counter-seasonal diversion for skiers and ski resorts alike. Early adopters at ski resorts installed bike carriers on ski lifts and then learned that if you allow bikes to the summits, you need designated downhill trails to avoid dangerous congestion on cat tracks and service roads, and free-wheeling damage to ski terrain.

It didn’t take long for resorts to recognize a business opportunity, and ski areas worldwide began clearing single-track biking trails for summertime visitors. Vermont’s Mount Snow opened one of the early lift-accessed, purpose-built bike parks in 1986. Whistler Blackcomb was another early adopter, adding bike racks to lifts in the mid-’80s and opening a bike park in 1999. A subgenre of mountain bike emerged, the high-speed downhill bike, with a heavy-duty steering head and shock absorbers, cushy saddle and powerful brakes.

Spurred by resort lobbying and support from major ski states, the U.S. Congress passed the Ski Area Recreational Opportunity Enhancement Act in 2011. Co-sponsored by Colorado U.S. Senators Mark Udall and Michael Bennet, the legislation expanded approved use of Forest Service land to include ziplining, rope courses and bike trails with associated facilities, among other non-winter activities.

Ever-evolving cycling technology now includes fat bikes, with their low-pressure, four-inch-wide tires allowing manageable use on snow. Exhibiting its own upgrades, skibob technology has greatly benefited adaptive skiing in the U.S. The wide range of durable, lightweight sit-skis and outrigger options has greatly expanded the sport.

In January 2018, Austrian cyclist Max Stöckl hit 64 mph on the Hahnenkamm’s Streif course, just prior to race weekend. He used a downhill bike equipped with studded tires. Perhaps showing the natural synergy between biking and skiing, Stöckl, who grew up near Kitzbühel, said he had to “really battle to clear the gates” and felt pressure to avoid crashing just days before the World Cup downhill.

“I wanted to offer the necessary respect by not ruining the work put in by the ski club by knocking out huge sections of fencing,” he said after the ride.

Shiffrin Wins Best Female Athlete Award

Adding to her record-setting year, Mikaela Shiffrin was named best athlete, women’s sports this summer at the 2023 ESPY awards gala.

The honor caps an extraordinary year for Shiffrin. With her 87th World Cup win in March, Shiffrin broke Ingemar Stenmark’s revered 86-win record that stood for 34 years. Not done yet, Shiffrin went on to add her 88th victory on the final day of the 2022–23 season. She also was named one of Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential People for 2023.

As she has done throughout her career, Shiffrin deflected attention from herself at the awards ceremony and—again— noted that records aren’t her priority. “Through failure and through success, it’s been a long journey, and it’s not over yet,” Shiffrin said from the stage.

“This season was absolutely incredible, and there was a lot of talk about records," she continued. "It got me thinking, ‘Why is a record actually important?’ And I just feel like it’s not important to break records or reset records. It’s important to set the tone for the next generation to inspire them.”

Shiffrin is only the second skier to win the best athlete ESPY award. Lindsey Vonn won back-to-back honors in 2010 and 2011. On the way to breaking Stenmark’s record, Shiffrin first eclipsed Vonn’s women’s World Cup mark of 82 wins.

Professional sports’ version of the Oscars, the made-for-television annual ESPY awards ceremony features glamorous red-carpet entrances, a packed celebrity audience and viral videos of acceptance speeches.

Stenmark has predicted that Shiffrin, 28, will reach 100 wins. She begins the defense of her overall 2023 World Cup crown in October at the traditional start of the race season in Sölden, Austria. —Greg Ditrinco

Snapshots in Time

1970 Hide Those Bumps and Bulges

The attention-getting power of tight pants paired with big, clunky ski boots has faded. The new head-turners fit sleekly over hips and thighs, but from there down, the line stovepipes or flares. Fewer bumps and bulges—now they can be hidden. It’s the year of the peacock for everyone, men included. The skier who stepped out of a mold is gone, we hope, forever. — Cathie Judge, “Kicky New Pants” (Skiing Magazine, January 1970)

1988 Speed Trap?

What has brought joy to users has become a mixed blessing to resort owners. The new high-speed quads cost two or three times more than the old lifts and their complex machinery makes them costlier to maintain. And when a quad replaces a conventional double chairlift, it dumps twice as many people onto the same amount of terrain. — John Fry, “Life in the Fast Chair” (Snow Country, October 1988.)

1990 Terrain Hogs: Expert or Beginner?

Who needs the most terrain on a mountain—the beginner or expert skier? Expert and beginner skiers pay the same for a lift ticket, but an expert gets more runs and uses more terrain. An average beginner manages 2,000 to 4,000 vertical feet in a day, compared to 10,000 to 12,000 feet for an intermediate and 20,000 to 30,000 for an expert. According to Sno.engineering, one acre of steep expert terrain will take care of three skiers at one time, but a one-acre beginner slope can accommodate as many as 20 skiers trying to master the sport. — Robin Dawson, “How Much?” (Snow Country, November 1990)

1993 More Aspen than Aspen

For the past several years, all the media hype about Telluride has made me avoid it entirely. There were horror stories of Oprah Winfrey’s $3 million “log cabin” and Sly Stallone’s custom-made Range Rover; reports of Donald and Marla’s slopeside trysts and a new spa as big and gaudy as a Las Vegas casino. There was a sea of condominiums, I’d heard, and a whole new population more gentrified than Aspen. — Pam Houston, “Saving Graces” (Skiing Magazine, December 1993)

2015 The Sound of Downhill Success

In an Alpine downhill race, there is no more lonely and solitary position than standing over a pair of skis hurtling down the mountain at 80 miles an hour.

The racer’s only companion is noise. In the merciless and nervy world of the downhill—the original extreme winter sport—sometimes the louder things get, the better. During a fast and sleek descent, the wind whistles around the body and through the small breaches in a skier’s helmet, creating an unmistakably shrill whistle that is one of several welcomed audio responses every competitor uses as feedback. — Bill Pennington, “In Delicate Dance with Gravity, Downhill Racers Are Soothed by Cacophony” (New York Times, February 5, 2015)

2023 $300 Day-Ticket Barrier Breached

Over the weekend, walk-up lift ticket rates at Arizona’s Snowbowl came in at $309 a pop. That’s not for a season pass. It’s for one day of skiing on the resort’s 55 runs. So, what gives? Dynamic pricing is what. Long a staple of the airline industry, dynamic pricing lets sellers jack up the rates when demand is high, penalizing people who didn’t plan ahead. — Sam Berman, “The Ski Area That Broke the $300/Day Lift Ticket Barrier Is Not One You’d Expect” (Skimag.com, January 23, 2023)