Short Turns: Abbreviated History of Ski Testing

Annual comprehensive ski testing has all but disappeared, along with its legacy print-magazine partners. Niche media look to fill the void.

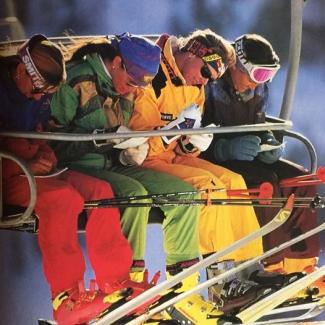

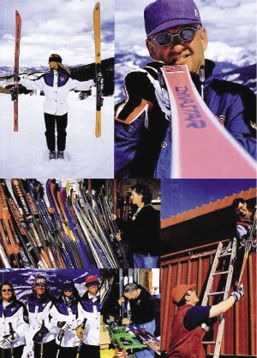

(Photo top: Testers for Snow Country magazine use a lift ride to fill out test cards in April, 1994. Courtesy RealSkiers.com)

In the spring of 1967, the editor of Skiing magazine, Doug Pfeiffer, invited Sven Coomer— then ski school director at Nevada’s Mt. Rose—and Jim McGill from California’s Big Bear to meet him at Mammoth for a six-week ski test session. Today, more than 50 years later, Skiing has long since been shuttered and the six-week ski test didn’t survive Pfeiffer’s tenure. The few on-snow tests that remain don’t last more than two or three days. This peek into the past traces the highs and lows of ski media’s attempts to evaluate skis based on their on-snow performance.

The impetus for Pfeiffer to test skis on snow came from Skiing’s publisher, Ziff Davis, whose cornerstone publications covered such fields as cars, motorcycles and cameras. These titles prioritized product reviews to establish the magazines’ bona fides as experts in their fields. Applying this formula to skis was practically foreordained.

Pfeiffer and Coomer hammered out a testing protocol and invited ski importers to send them their latest and greatest for evaluation. However, a couple of problems popped up immediately. First and foremost, many of the skis arrived in unskiable condition, with railed edges or wavy bases, which would mask any attempt to evaluate them fairly. Hand-tuning the skis took hours of hard work; the wet-belt sander wouldn’t be introduced until 1972, and the stone grinder in 1974. In that era, skis delivered to shops were generally in no better shape.

Even though most suppliers—Atomic being the lone exception, according to Coomer—had delivered unskiable samples, they lobbied to suppress any negative reviews. Ski testing was still foreign to the European markets, and the suppliers of the day didn’t want upstart Americans criticizing their star products. A revolt ensued on the supplier side, but Coomer defended the integrity of their testing methods, which were much more thorough than anything being done today. (For example, today no one bothers to measure the camber line of so much as a single ski, much less collect any other data not shown in the catalog.) As product testing was integral to the Ziff Davis brand, the publisher stood behind the ski-testing protocol and the supplier rebellion was stifled. Pfeiffer’s on-snow testing and consequent ski reviews would run until 1974, when he was pushed out and began writing for SKI.

Until then, SKI’s forays into equipment coverage had been spotty, as its editor, the brilliant John Fry, preferred to focus on instruction and technique. The early high-water mark occurred in 1968, when the magazine surveyed 100 instructors about their experience with 35 ski models from 17 brands. In 1970, a more tepid effort engaged seven editors to review 23 models.

When SKI decided to ramp up its gear coverage, Henri Patty at Rossignol used his leverage as a major advertiser to squelch the idea by threatening to boycott on-snow tests. SKI’s publisher backed down, and so did Ziff Davis, effectively ending on-snow testing at both magazines. From 1975 to 1981, SKI and Skiing cobbled together reviews based on the perceived design intent of a ski, bolstered with marketing blather, factory visits, interviews with designers and bench tests; in other words, just about everything but on-snow evaluations.

To plug this hole in its coverage, SKI had contracted with John Perryman, a former Head engineer who created a series of workbench tests that would ostensibly be more scientific than the anecdotal notes of a tester on snow. The “SKIpp” tests (SKI Performance Prediction), as Perryman’s notion was titled, sounded air-tight on paper but utterly failed at predicting ski behavior. Aside from being unbearably arid, rinsed of all the nuanced behavior on-snow testing might have revealed, Perryman’s reviews rarely reflected real-world performance.

The SKIpp protocol was euthanized with the arrival of associate editor Seth Masia in 1974, but it would be several seasons before on-snow testing was reinstituted. In the meantime, working through the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM), ski factories standardized bench-testing procedures so that every lab, and magazine, produced comparable data.

In the fall of 1975, SKI dedicated 18 pages to equipment coverage, beginning a ritual that would last until the death of print. By 1978, the fall gear reviews were trumpeted on the cover, but a full-blown buyer’s guide that would occupy an entire issue didn’t materialize until 1983. Meanwhile, in 1981, Bill Grout, then senior editor at Skiing, began to supplement bench-test data with informal impressions from a handful of testers. Over the next two winters, he gradually resumed formal testing. Challenged, Masia organized an on-snow test in late March 1982 at Alpine Meadows, but it was cancelled by a massive storm. The following year he recruited instructors to test skis at Palisades Tahoe (née Squaw Valley) and by 1984 both magazines were back in the on-snow testing business.

Masia soon was given the green light to engage a larger team, equipped with test cards that broke down ski behavior into phases of a turn and other criteria that together provided a composite picture of a given ski’s performance envelope. The arrival of Ed Pitoniak as top editor resulted in a major budget commitment to testing, allowing Masia to load up on skiing luminaries who gave the test results both credibility and cachet. SKI moved its week-long springtime test camp to Beaver Creek and employed two dozen instructors and racers to review up to 120 skis. Later, SKI’s template became the model for ski publishing arriviste Snow Country magazine, where this writer presided over all Alpine equipment coverage.

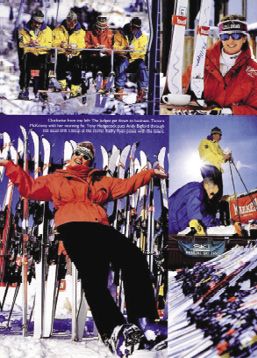

While Snow Country copied some of the characteristics of SKI and Skiing’s gear coverage, it differed in several key details. Snow Country didn’t try to cram all models into a five-day schedule and instead took nearly a month, fashioning a test team according to the genre under review (i.e., mogul ski champions like Cameron Boyle, Scot Kauf and Wayne Wong skied bump skis, ex-racers skied race skis, etc.). We usually didn’t ski more than 12 models a day and were off the hill by 11:00, before the snow devolved into spring slop. Perhaps most importantly to the supplier community (and readers, one hopes), we published our results in their order of finish, creating one champion and a host of also-rans.

Once again, it was Rossignol that blew a fuse. Jacques Rodet, whose bombastic style usually cowed all who dared cross him, demanded we retest one of his star models, which our results had dropped to the middle of the pack. We did, but it didn’t change the model’s sorry standing. Rodet demanded a pow-wow in the Snow Country offices, which became a round table comprised of every major brand’s chief marketing executive. Snow Country stood behind my methods, other brands concurred, and Rossi’s initiative was scuttled.

Flash forward to today, and the major print titles that serviced mainstream Alpine skiers are all gone or so transmogrified by their transition to the digital world that their credibility has crumbled. (More narrowly focused constituencies, like backcountry skiers or pipe-and-park aficionados, remain well served by print titles.) Filling the void left by the likes of SKI, Skiing and Snow Country are a host of online vendors (including Realskiers.com and what’s left of SKI, which many feel lost whatever cachet it had left when it fired Mike Rogan, a brilliant skier and ski tester) who cobble together teams of skiers whose main qualification seems to be their availability.

Looming over all contemporary ski reviews is the specter of AI, which seems capable of producing apparently plausible evaluations—in whatever style or tone one requests—in less than a minute. AI, of course, can’t ski.

Caveat emptor.

Snapshots in Time

1949 The World According to Lunn

Let me say this. The important thing about a teacher is not whether he is Swiss or French or Austrian, but whether he is a good teacher or a bad one. Good teachers are rare, but they are found in all countries. — Arnold Lunn, “Do Skiers Really Ski Today?” (SKI Magazine, December 15, 1949)

1964 Beattie’s Egg-cellence

As they schussed their way toward the Winter Olympics at Innsbruck. Austria, the U.S. Alpine Ski Team was looking great and feeling cocky. Both their skill and their new confidence were the work of their frosty-looking ski coach Bob Beattie. In a few months he has turned America’s men’s team—traditional Olympic also-rans—into formidable contenders. A controversial innovator, Beattie speeded his skiers in downhill by making them hold a streamlined “egg” position even when their skis were off the snow. He cut their time on slalom runs by concocting a maneuver called the “dyna-turn”—and making them use it whether they liked it or not. — “Our Ski Team Flies High” (Life Magazine, January 10, 1964)

1974 No Technique Nuts Here

Hurray for Warren Witherell’s article (“Sitting Back Is Nonsense”). There are many recreational skiers who love the sport and think as he does. We are not racers, not technique nuts—we just enjoy the way we ski and don’t feel we have to conform to the ski-back style just because it’s the newest thing to come down the pike. — Virginia Kanick, New York, N.Y., “Witherell Disputed” (Letters, Skiing Magazine, Spring 1974)

2005 Smoked Out

When Black Mountain opened for the season on Dec. 10, it became the first ski resort in the nation where tobacco use was banned everywhere, including the lodge, the Alpine and cross-country trails, and the lifts, state and industry officials said. But it probably will not be the last. “In many other areas, it’s fairly common to say ‘no smoking’ in a building, but this is the first area to say ‘no smoking’ in parking lots, in base areas and on lifts,” said Michael Berry, president of the National Ski Areas Association, a trade group in Lakewood, Colo. “I think it’s been noticed. I think it’s the beginning of a trend I think you’ll see more of.” — Katie Zezima, “Maine Ski Resort Tells Smokers They Can’t Light Up (No, Not Even in the Cold)” (New York Times, January 24, 2005)

2024 Utah Gets the Winter Olympics—and a Request

What was expected to be a simple coronation of Salt Lake City as the 2034 Winter Olympic host turned into complicated Olympic politics, as the IOC pushed Utah officials to end an FBI investigation into a suspected doping coverup. The International Olympic Committee awarded the 2034 Winter Games only after a contingent of Utah politicians and U.S. Olympic leaders signed an agreement that pressures them to lobby the federal government. The IOC is angry about an ongoing U.S. federal investigation of suspected doping by Chinese swimmers who were allowed to compete at the 2020 Tokyo Games. Even in the world of Olympic diplomacy, it was a stunning power move to force officials to publicly agree to do the IOC’s lobbying. — Graham Dunbar, “IOC Awards 2034 Winter Games to Utah and Pushes Officials to Help End FBI Investigation” (Associated Press, July 24, 2024)