Mike Douglas: Godfather of Freeskiing

Revolutionizing gear and transforming media, Douglas led the way.

Back in high school, all Mike Douglas wanted from Salomon were the gloves and the kneepads. He’d go into the local ski shop, Action Sports in Campbell River, British Columbia, and watch skiing videos. “The coolest skiers all had the blue kneepads with the big ‘S’ and the matching white gloves,” he says.

(Photo top: As a member of the Canadian Air Force, Mike Douglas bombs Whistler-Blackcomb powder. Courtesy Mike Douglas.)

Little did he realize what kind of impact Salomon SA, a French brand that was only known for making ski boots and bindings back in 1985, would have on his life. Nor would the Savoyards realize how a kid from Vancouver Island would help them become a global sporting giant.

Growing up on Vancouver Island was a surprisingly isolating experience, in retrospect. “Powder magazine was our only connection to the outside world,” Douglas told podcaster Mike Powell in 2016. Halfway through his first semester at the University of Victoria, Douglas moved to Whistler, he says, to “get skiing out of his system.” He started hanging around with established freestyle talents like John Smart from the Blackcomb Freestyle Team and began badgering photographers so that he could get into magazines and line up sponsorships. He progressed quickly, finishing in the top three in both moguls and aerials in the 1989–90 season, then moved up to the Canadian national team a year later.

From 1989 to 1993, Douglas gave it his all in an attempt to gain a spot on the Canadian Olympic team—only to be named as “first alternate” for the Lillehammer games in Norway in 1994. Douglas told Powell, “Four of the six top mogul skiers on the World Cup at the time were from Canada, but I wasn’t one of them. I got measured for the uniform in case another member got sick or injured, but never made it to the Games.”

Needing to earn some cash to stay in Whistler, Douglas started coaching for the Blackcomb Freestyle Team. It was a summer spent coaching and skiing on Blackcomb Mountain’s Horstman Glacier that changed his trajectory—and the sport of freestyle—forever. “I was the Canadian development team mogul coach, coaching JF Cusson, JP Auclair and Vincent Dorion at the time,” says Douglas. “After our mogul-training sessions, we’d hit the jumps and halfpipes at the snowboard park and imitate their maneuvers on skis.”

It was a dizzying world, where snowboarders would alley-oop out of a halfpipe and rotate their bodies once, twice, three times before re-entering the half-pipe orbit. Because snowboarders rode at right angles to the fall line, they could spin and land on their dominant leg, or “switch.” The squared-off tails of the dominant mogul skis being used at the time precluded any smooth backward landing.

The impetus to create an entirely new ski—one that would ski almost as well going backward as forward—came from the Japanese team’s mogul coach, Steve Fearing, who “pushed us to conceptualize what our perfect ski would be,” Douglas says.

“We strategically made the decision that we didn’t want to just have a company make what they thought we needed,” he continues. “We were adamant about the design of the skis. We put together quite an impressive video presentation and put it in front of the nine biggest ski companies at the time, but it was rejected by pretty much everyone except for Salomon. Some companies were happy to sponsor us as skiers, but we needed a twin-tip ski that could take the sport into the future.”

In the 1980s, several prominent French Canadian freestyle skiers were nicknamed the Canadian Air Force for their innovative maneuvers in moguls and on the aerial ramp. As a tribute to their mentors, in 1995 the four Salomon skiers would be dubbed the New Canadian Air Force, and Douglas, their coach, would henceforth be known as the Godfather of New School, or the Godfather of Freeskiing. Douglas had always been interested in filmmaking and even made a ski video as part of a class project in high school. From the beginning, Douglas filmed his protégés’ exploits at the summer training camps.

Douglas and his posse eventually signed a contract with Salomon, but the early prototype skis from France were terrible. “This was when carving was big, especially in Europe. Their designer turned the tails up on a 152-centimeter ski called the Axe Cleaver and expected it to work,” Douglas explains.

Ski historians will note that Olin and Kästle, amongst others, made twin-tip skis for ballet back in the 1970s. The TenEighty, however, was nothing like the straight-sided dance numbers used by Alan Schoenberger and Suzy Chaffee. Salomon’s new pipe-and-bumps ski proved to work magic.

Douglas says, “In February of 1997, we got our very first production models, just after JP won the Big Air title at the first U.S. Open of Freeskiing held in Vail.” When the 1998 season hit, “everyone wanted a piece of the TenEighty. It totally blew up the year after Salomon introduced it, and they really got it right this time,” he says. Twenty years later, Douglas would commemorate the ski in a Salomon Freeski TV video called Becoming History: 20 Years of the TenEighty.

While there were worthy twin-tips made by Line, K2, Dynastar and others, the lively pop of the TenEighty’s cap construction and its relatively wide waist profile made it a ski that excelled at park and pipe; and, indeed, all over the mountain.

As the New School movement boomed, so did a whole new range of aerial tricks in the halfpipe and later, the terrain park. Skate- and snowboard-inspired flips, spins, grabs and rotations became the norm. The TenEighty takes its name from the skier boosting three consecutive 360-degree rotations before landing—one thousand and eighty degrees. Douglas himself is credited with inventing the “D-Spin,” a corkscrew-type move that combines a backflip with two complete body spins or rotations.

An entire ecosystem of events took place that often combined skiers and boarders competing in the same terrain parks and halfpipes. After a couple of years of competing in the nascent ESPN X Games, Douglas provided color commentary for the skiing events. The inclusion of slopestyle, halfpipe and big air showed that indeed, “skiing was cool, again.” The TenEighty and its various clones had a knock-on effect that continues to this day; sales of twin-tip skis skyrocketed, while snowboarding’s growth flattened, and then almost flat-lined.

From a visual perspective, the next progression of New School skiing was to take twin-tip skis into the backcountry and use natural features like cliffs, wind-lips and cornices. Again, Douglas and Salomon were ahead of the curve in developing the ridiculously user-friendly TenEighty Pocket Rocket, a floaty, wide powder ski with turned-up tails styled from the original TenEighty. The Pocket Rocket’s appeal went far beyond the jib set, however, and became the ski of choice on big powder days at Whistler Blackcomb, Douglas’s home mountain. Park rats could now flip and spin in spectacular natural locations around the world, accessible via snowmobile, helicopter or even on foot.

By the time Salomon discontinued its run, the TenEighty had become a brand unto itself, with almost 50 different topsheets and iterations, from mogul skis to athlete signature skis to the immensely successful X-Scream mid-fat ski.

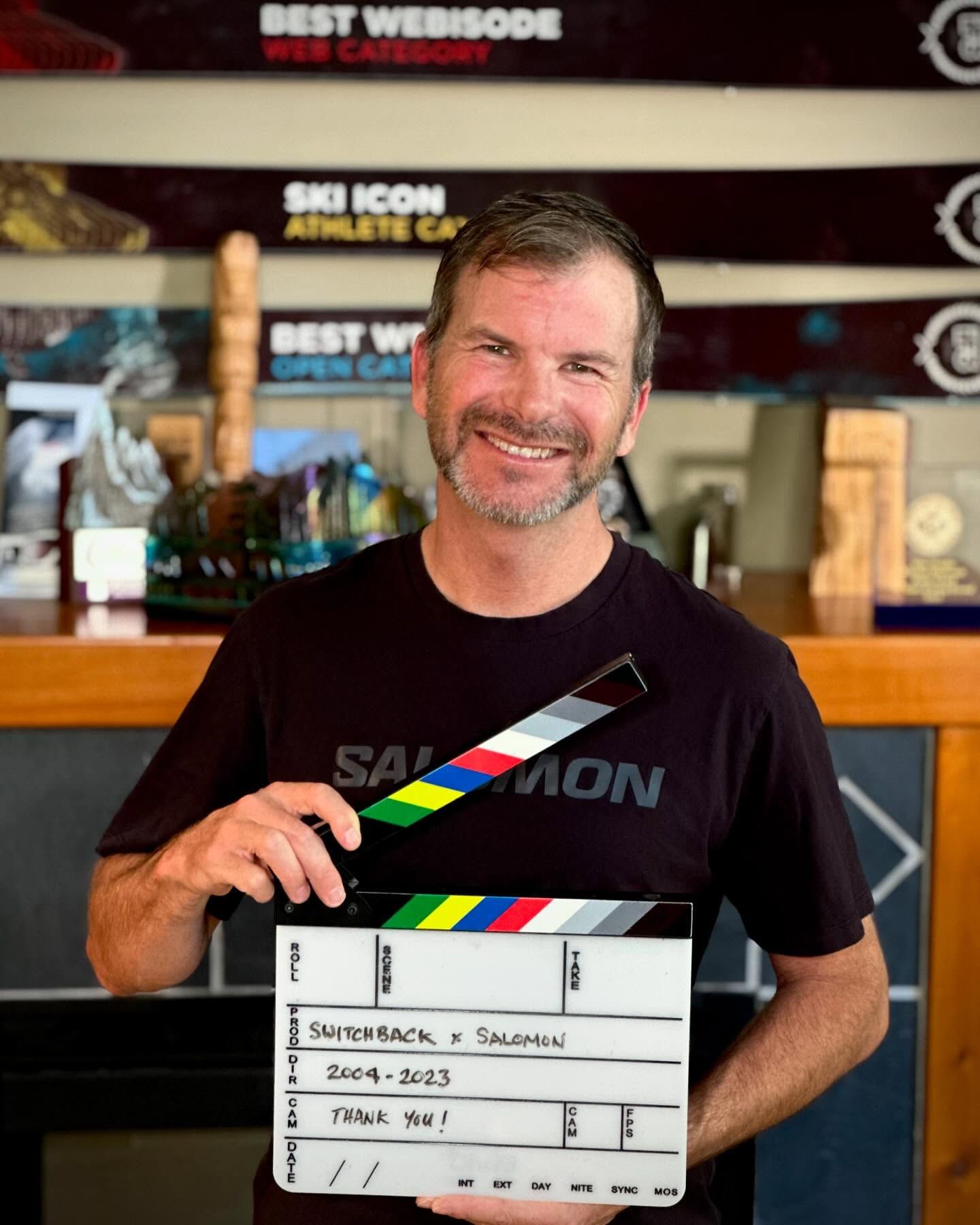

While working at ESPN, Douglas learned how big-budget events were covered and in 2004 formed Switchback Entertainment, his foray into filmmaking. “At the time, ski companies had to shell out money for their athletes to appear in Warren Miller, Matchstick Productions or TGR movies, says Douglas. “We went to Salomon and said, ‘How about we try something different? We have the talent and I have a lot of ideas.’”

The clincher for Salomon came when Douglas asked how familiar its marketing team was with YouTube, the new online streaming service that was quickly becoming an obsession with the kids. He proposed that Salomon not go down the path of feature-length DVDs that were favored by other ski companies and instead produce films for a “Salomon Freeski” channel on YouTube. “Let’s look to the future,” Douglas pitched to Salomon. “We can produce five-minute movies or 45-minute documentaries. YouTube doesn’t care how long the content is.”

In a sense, Salomon’s Freeski TV YouTube channel proved as revolutionary from a media perspective as the TenEighty had been from the gear side. Both took an existing format and changed it into something similar, but also completely different. Salomon Freeski TV changed not just the delivery system, but the culture of storytelling around the sport as well.

Salomon got it. And the viewer numbers, which were a challenge to pin down using traditional media-tracking methods, proved exceptional. Rather than filming for one major production each winter, the way that Warren Miller might, Switchback could produce wildly disparate segments that might appeal to different audience demographics. “We started with a fairly conservative variety show concept, but the Freedom Chair broke the mold in so many ways,” Douglas says.

Freedom Chair tells the story of Josh Dueck, a freestyle ski coach from SilverStar Mountain Resort in Vernon, B.C. Under his tutelage, Dueck’s charges had become some of the best New School skiers in the world. Their members included Josh Bibby, Riley Leboe and TJ Schiller—early-adopter pro skiers who made a name for themselves in front of the camera and on the X Games podium. While demonstrating a big-air maneuver to junior-club skiers at SilverStar’s freestyle site, Dueck overshot the landing area, crashed and crushed his spine. Dueck ended up paralyzed from the waist down. He could have chucked the sport and reframed his life, but he doubled down, becoming a multiple-medal winner in Paralympic sit-skiing. Douglas, who knew Dueck through his freeskiing connections, started documenting his racing success but then hatched a daring plan that would eventually see Dueck perform the very first backflip ever on a sit-ski.

From the moment Freedom Chair was screened at film festivals around the world, audiences cheered and were moved to tears by Dueck’s determination, humility and grace in living with what is still a hugely challenging, life-changing, and ongoing situation. Freedom Chair did something that Douglas had wanted to do from the very beginning: create a human-interest saga that you wouldn’t need to be a skier to appreciate.

As Salomon Freeski’s YouTube numbers exploded, Douglas hired Jeff Thomas and Anthony Bonello, immensely creative talents in their own right. They produced snowsports documentaries that featured tight, focused storylines, stunning visuals and concepts so far out that they almost beg description. For instance, they flew to Greenland to film a skier passing through a solar eclipse.

In September, Douglas announced via social media that his long-term relationship with Salomon SA had evolved; he would no longer be involved in the content creation side of things. But he’ll still be the Godfather of New School and a paid Salomon brand ambassador with a focus on ski- and clothing production sustainability.

Douglas, now 55, is a natural to lead Salomon into a new era of environmentally conscious product development. From 2018 to 2023, he fronted the Canadian chapter of Protect Our Winters, the international environmental advocacy group launched by snowboarder Jeremy Jones. Douglas probably has a deeper knowledge of climate challenges than any other skier currently sponsored by a major company. He’ll also work with Salomon-sponsored athletes, designers and production managers on a variety of initiatives, such as creating awareness around PFAS-free textiles used in ski clothing.

In the meantime, Douglas is busy finishing a passion project that has nothing to do with skiing. It’s a feature documentary titled The Impossible Journey, about Danish adventurer Thor Pedersen’s mission to visit every country in the world without flying. Douglas hopes to have it entered into film festivals in 2025.

Vancouver-based contributor Steven Threndyle reviewed the book I Survived Myself in the July-August 2024 issue.