Leni Riefenstahl - Leni Riefenstahl, Ski film star, Nazi director

Leni Riefenstahl

Controversial Journey from Ski Film Star to World Renowned Director

By Morten Lund

The late Leni Riefenstahl was an extraordinary actress in ski and mountain adventure films. She rose in power to become an even more extraordinary director of documentary film spectaculars.

Her two great documentaries, the 1935 "Triumph of the Will," and the 1938 "Olympia," are classics whose drive and beauty, so some historians of film feel, remain unmatched. But they were produced with the financing and cooperation of the Nazi party under direct orders from party leader Adolph Hitler. Therein lies the controversy.

In the 1920s, Leni went from her self-created profession as an actress-dancer, successfully staging her own modern solo dance dramas on the Berlin stage, to fame as early film actress under the direction of Arnold Fanck, the great pioneer of outdoor adventure films.

Fanck's first film, on the ski ascent of Monte Rosa in 1913, set a pattern that he continued after World War I. In 1920 Fanck made "Wonders of Skiing," and in 1921 he filmed "Fox Chase in the Engadine," with Hannes Schneider, then one of the best known skiers and ski school directors in Europe. Also in 1921, Fanck branched out into fiction with his adventure drama "Battle Against the Mountains."

Shortly thereafter Fanck met Leni Riefenstahl and became enamored of her creative spirit as well as her physical beauty. First Fanck cast Leni opposite Hannes in Schneider¹s own biography, the 1926 "Hannes Schneider," in which Leni played the ski pupil. Thereafter, she starred in all Fanck's adventure dramas as the romantic female lead, beginning with the 1926 "Holy Mountain," during which she insisted on learning to excel in skiing, and that led to a twisted ankle. She finished the film in spite of the pain. In 1930, Fanck again cast Leni opposite Hannes in "White Ecstasy," another ski chase film, this time with Leni and Hannes as the foxes and the St. Anton ski school instructors as the hounds.

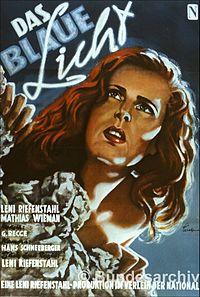

In those days ski films were popular with general audiences and "Ecstasy" was such a success that in 1932 Leni was able to get financing for her own film, "The Blue Light," based on German folk myth. Hitler, by chance, saw the film and was so taken by its blend of mystical power of mind and physical strength that he arranged to meet Leni. He offered her the chance to film the documentary of the 1933 rally of the Nazi party, and she did it, with limited funding.

In 1934, after he had been elected Chancellor of Germany, Hitler had Leni film the 1934 Nazi rally at Nuremburg, which she produced as "Triumph of the Will" after a year of editing. She had been afforded dozens of cameramen, and the technology with which to invent techniques. She introudced the high overhead crowd shot, and put her cameras on rails so she could track with a moving camera -- two of her innovations avidly copied by filmmakers in both drama and documentaries.

Then Hitler gave Leni carte blanche to film the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, and again, no cost was spared. She used 170 cameramen. "Olympia" is generally considered an apex of the documentary genre, lovingly edited over the two years that Leni took to make an epic starring, as it were, the human form in all its athletic power. Again, her innovations -- slow motion, close overhead shots, dramatic cutting -- inspired a generation of documentary filmmakers. To her credit, in "Olympia" Riefenstahl departed from the Nazi line by featuring American superstar Jesse Owens prominently.

After World War II, Leni fell as fast and as far as her Nazi sponsors. Although she had never joined the Nazi party, the Allied powers that took Germany over felt she had aided Hitler's rise to power. She was labeled a "Nazi sympathizer" by the Allied authorities and for nearly a decade was not allowed to make films. She produced one film "Tiefland," that she had already shot, but after that no one would back her for a new film.

Leni recreated herself as a still photographer and worked at it almost to the day she died. Her photo essays on African tribesmen and her underwater photography, shot after she learned to scuba dive in her 90s, displayed as deeply as ever her trademark balance of strength and delicacy. Finally, whatever else she was, Leni was an unquenchable incarnation of the marriage of mind and physical strength -- she was the aesthetic voice of a Fascist concept. Leni stubbornly lived on for 58 years beyond the death of her patron.