The 1930s: The Unexpected Blossoming of Alpine Skiing

Authored by Morten Lund

In the 1930s, alpine skiing made the transition from an exotic, leisure pursuit for a number of skiers estimated in the low five figures at the end of the 1920s to become a worldwide participant sport. The growth was so rapid that National Ski Association president Roger Langley announced in 1936 that there were a million American skiers. Ski historian John Allen rightly says that “no one really knew.” The most credible estimates range from a quarter of a million to not more than half a million U.S. skiers in 1936.

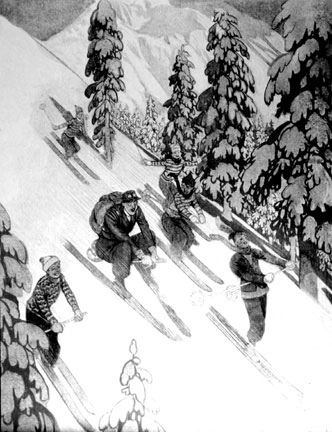

In any case, alpine skiing had unexpectedly become a success in the United States as well as in Europe. Sepp Ruschp, arriving in 1936, at Stowe, Vermont, from Linz, Austria, noted that the day he left Austria there were six hundred certified instructors working in the Austrian resorts. A graphic rendering of the kind of crowding that followed skiing’s escalating popularity was given in a large sketch by “Samivel,” published in 1931, making Samivel’s entry as a fine talent in ski cartooning. (Samivel is a pseudonym, taken from a Charles Dickens character.) Any attempt to explain the process by which the few thousand skiers of the early 1920s became the hundreds of thousands of the 1930s has to take into consideration French savant Henri Bergson, who warned against “the illusions of retrospective determinism.” As popular historian Timothy Gorton Ash recently wrote, “You can always find more than sufficient causes for every great event—after the event.”

It would have been easy to explain if alpine skiing had declined during the 1930s by pointing out that the decade marked the height of the Great Depression. But skiing did not decline. Its growth accelerated instead. A half dozen reasons come to mind explaining— even if not entirely—the unexpected phenomenon of this blossoming of alpine skiing.

The proliferation of the rope tow is one key. In 1929, only one lift installed at Hilltop in Truckee, California, was operating in the U.S. It lay on the snow, a wire cable with hooks attached, a haulback tow pulling mostly toboggans and a few skiers. Three years later, in 1932, the first rope tow was patented in Zurich. The very next winter of 1933, the first North American rope was up and running at Shawbridge, Quebec, in the Laurentians. In 1934, the first U.S. rope was installed at Woodstock, Vermont. The rope was relatively easy to build and cheap to install and spread like wildfire.

In 1937, the American Ski Annual counted a hundred tows coast- to-coast. All but a dozen or so were rope tows. Many of the ropes were conveniently situated, close to towns and cities, making entry into the sport easy in every sense. The state of Maine eventually put up over a hundred rope tows. Ski Area Management publisher Dave Rowan writes, “The climbing ethic was not for everyone. Not having to climb triggered the growth.”

The prime excitement of alpine skiing fed on a lack of alternatives during the winter months. There were no superhighways to warmer climes, no jets to Miami, no television, no Internet. There were other winter outdoor sports: hunting, sledding, skating, tobogganing, iceboating, snowshoeing, and ski touring. None of these threw off the electric attraction of alpine skiing.

Glenn Parkinson, author of the Maine ski history book First Tracks, says that when the state’s first rope tow opened in 1936 at Fryeburg, Maine, two hundred people came to ski and three thousand came to watch; when the Maine governor opened a rope tow at Waterville, 10,000 spectators showed up.

Then there was the glamor of resort skiing, magnified a thousandfold by films and magazines. By 1940, the U.S. had twenty big lift resorts coast-to-coast, from Sugar Bowl, California, to Cannon Mountain, New Hampshire.

“Even among the less affluent, there was no comparable activity for upscale, outdoorsy people,” Dave Rowan writes. “… it became the great mating scene. If you wanted to be seen as a ‘sport,’ which was the operative word in the 1930s, you skied in the winter. The sport developed its own clothing glamor, its own songs, its own mystique, its own heroes both European instructor-gods and homegrown racing heroes.”

A major contribution came when snow trains began to run. (So much so that the January 23, 1937 cover of the New Yorker featured a snow train arriving at a small mountain town.) The first eastern snow train ran from Boston to Mt. Kearsage in New Hampshire, in 1931. By 1940, snow trains were lugging thousands of skiers every weekend to points in eastern snow country, and in the Sierra as well.

There was a major new recreation in the works and it was not going to go away. U.S. entry into World War II in 1939 slowed the process down, putting a stop to all major lift-building but growth resumed with a vengeance after the war.

The growth of alpine skiing inspired a flood of new ski books. The best available estimates show roughly a hundred or so ski books being published from 1900 to 1920. The rate tripled from 1920 to 1940, when some three hundred ski books were published. A number of outstanding ski cartoon books were published in German, German-speaking countries having by far the largest skiing public. One of these contains Hans Görg Schuster’s cartoons, the 1937 Skibrevier, that is “Dispatches from the Ski Front.” The book gave evidence of the truth that alpine skiers were drawn from the educated and well-to-do and, for them, ski resorts were a big draw.

Skibrevier pairs quotations from works of Schiller and Goethe with sketches (shown at right), indicating that skiers were educated and had the income to take their families to resorts. Or if not the family, then the neophyte girlfriend, the skihaserl, or ski bunny: alpine resorts and skihaserl appear in the Alps simultaneously, coming together synergistically. Skibrevier’s Das Lied vom Skihaserl, “The Song of the Ski Bunny,” runs as follows:

- A ski bunny sets your heart to beating

- She gives joy to old and young

- A most joyous ski companion

- She always happy, never glum.

- Yes, you’ve got to have a bunny

- Without her skiing is no fun.

During the 1930s, U.S. magazines began to reflect the growing recognition of skiing as a popular sport. At least four national magazines ran ski cartoon covers during the years 1935-37.

The New Yorker of January 26, 1935 and the February 1935 Judge both ran covers showing what purports to be recreational ski jumping, although there was not much casual, recreational jumping around. Jumping in the main was done by highly-trained athletes such as those taking part in the 1932 Olympics at Lake Placid, where ski jumping was the big ski event—there were no alpine events allowed at Lake Placid. Result: in the post-Olympics years, jumping got much more coverage than alpine skiing. Jumping guaranteed more dramatic news photos than alpine racing could deliver.

The consequent emphasis on jumping must have led cartoonists to believe that there was a good deal of recreational jumping out there, which may explain the deftly-sketched but unrepresentative national magazine covers.

Generally speaking, ski cartoonists of the 1930s stuck loyally with their favorite accident-strewn winter sport, alpine skiing. Collier’s ran a cover January 24, 1937 showing alpine skiing as a crash-and-burn business—a solid cartoon tradition at this point. Unfortunately, there was still a good deal of truth to that idea. Americans had a long way to go before the sport could qualify as a rational pursuit.

Too many American skiers ended their season by fracturing a major limb. Even good skiers suffered injury all too frequently. Roland Palmedo, president of the Amateur Ski Club of New York, fractured an ankle in 1933. His fellow club officer, Minot Dole, broke his ankle at Stowe three seasons later. That same season Dole’s friend, Frank Edson, was killed racing in Massachusetts. The founder of the Eastern Slopes Ski School, Carroll Reed, broke his back racing in New Hampshire. Almost every veteran skier in the 1930s broke something at one time or another.

Instruction was the answer but, in the mid-1930s, skiing was being taught by instructors attached to individual clubs or hotels, notably at the exclusive Lake Placid Club in New York and at Peckett’s in New Hampshire. Then there were independent instructors working with ski clubs in the U.S. Eastern Amateur Ski Association.

The technique taught could vary considerably from one situation to the next. Although the core stem turn progression—snowplow, stem, stem christie—first invented as part of the “Arlberg technique,” finally prevailed almost everywhere, it took most of the decade for that to happen.

The stem turn progression found its earliest U.S. school at the Lake Placid Club after the Marquis d’Albizzi and Ornulf Poulson began instructing there in 1920, teaching stems along with nordic turns. Erling Strom took Poulson’s place in 1928, remaining until 1938. He focused more and more on stem turns, in part because the new boots and bindings were increasingly less-suited for nordic technique. In 1928, Otto Schniebs, a certified instructor from Germany, emigrated to the U.S. to work for Waltham Watch in Waltham, Massachusetts, and began teaching Arlberg on hills around Boston. Schniebs became the ski instructor for the then influential Appalachian Mountain Club. From 1930 to 1936, he headed the ski program at Dartmouth College, making him a key figure in propagating stem turns on these shores. Another important promotor of the stem technique was Sig Buchmayr of Salzburg, Austria, teaching at Peckett’s-on-Sugar Hill in Franconia, New Hampshire, beginning in the 1930-31 season. He ran the school for eight seasons thereafter, increasing the number of instructors teaching stem turns each season. The first certification course for amateur instructors was held in 1933 by the U.S. Eastern Amateur Ski Association at Dartmouth College under Otto Schniebs. Nineteen candidates showed up, and only 11 passed. The grip of stem turn technology was strengthened again in 1936 when the Mt. Mansfield Ski Club hired Sepp Ruschp, a certified Arlberg instructor from Linz, Austria, for the 1936-37 winter season.

All during the 1930s then, a handful of proficient stem progression instructors in the U.S. exerted an influence out of all proportion to their numbers. These included Schniebs who in 1936 took over at the Lake Placid Club; Walter Prager (succeeding Otto Schniebs at Dartmouth), the Klein brothers at the Sierra Club lodge in Donner Pass, Hannes Schroll in Yosemite, California, Otto Lang at Mt. Rainier, Benno Rybizka in Jackson, New Hampshire, and Fritz Steuri at Woodstock, Vermont.

But these fine Austrian, Swiss and German instructors were still relatively few in number. Thousands of ignorant skiers remained at large, cruising the American slopes.

The situation in the U.S. was admirably conveyed by the first notable American cartoonist Max Barsis. His impressions of the primitive American ski world, shown on the following pages, sketched in his 1939 Bottoms Up remain classic. (It was the first of four Barsis books depicting the reality of the sport from the skier’s viewpoint.)

To ski in the 1930s meant to love the sport beyond all reason. There is a most poignant essay in point by Allen Adler in his New England & Thereabouts—a Ski Tracing, describing a day in the life of the 1930s skier:

Vaulting the running-board into his Essex Terraplane of a winter Friday evening, he heads up a numbered U.S. route, cruising at 35-45 miles per hour—no Interstates back then… . The low-range AM radio crackles with static and, as he moves from one frequency to another, voices and music frequently intermingle… After seven to twelve hours, he pulls up in front of a farmhouse or lodging with a “Skiers Welcome” sign out front. …he unloads his ridge-top hickory skis with screwed-on Lettner edges…and front-throw cable bindings. His ski boots—leather, square-toed, laced, ankle high—have been on his feet since leaving home…Up early, he checks the thermometer, then spends some forty minutes waxing his skis with a hot iron…he heads for the slopes dressed in…blousy ski trousers which he endeavors to keep taut with suspenders…Topping all this is a navy blue ski cap, peaked and with ear flaps that tie over the top. At the slopes he pays his two dollars … and takes the rope tow to the top… if wet, the rope is also heavy and it is advisable to ride about twenty feet behind the skier directly ahead…The rope twists and he need be careful not to catch the long cuff of his mittens… he is certain to return home with dried white rope streaks on his trouser thighs. The trails are narrow…packed only by the skis of other runners. Come lunchtime and he removes a couple of sandwiches, an orange and a thermos of coffee from his day pack…in the rather rough building that serves as the base house. …The johns are not much more than attached outhouses …no one seems to notice. They came for the sliding and that is on the hill…at day’s end, he returns to his lodgings where…he and the other guests gather in front of the woodstove in the parlor to dry boots and socks, drink a little beer…and sing a few ski songs before retiring. -- Morten Lund.

For another explanation of the 1930s boom in Alpine skiing, see Alpine Revolution.