From Jet Stix to Tinkle Tabs, these crazy ski products faded, fizzled or failed to stand the test of time. By Jeff Blumenfeld

As empty-nesting downsizers moving from Connecticut to Boulder, my wife and I had to contend with the accumulated flotsam of 30-plus years of marriage. It was especially hard to part with ski equipment, apparel and accessories. Each imparted great memories of days spent on the slopes.

I gave away my Graves skis. I unceremoniously pitched the Kneissl Blue Star OPs from the early 1980s, along with my Cevas and Club A one-piece suits.

But I couldn’t say goodbye to my Ski Wings. Yes, Ski Wings—butterfly-shaped air scoops that attach to ski poles. Four aerodynamically balanced nylon pockets form a cushion of air in front of you. Head straight down a steep bump run and you feel like you’re flying as you literally skim across the tops of moguls.

Originally known as ski sails, this odd product dates back at least as far as Leo Gasperl (1932) and Stein Eriksen, who used them in 1968–69 at Snowmass in Colorado (Skiing History, July-August 2011). They have since been reinvented in Europe as Wingjumps, “the first skiing equipment to offer the feeling of being lifted while skiing, in complete safety!” (That claim, of course, remains to be seen.)

What is it about skiing and snowboarding that inspires budding inventors?

“Scores of ingenious Rube Goldberg ideas have invaded the sport throughout its history,” writes ISHA chairman John Fry, author of The Story of Modern Skiing (UPNE, 2006). “There was a ski whose performance could be altered by pumping air into it. Another ski contained rods that you could tighten and loosen to adjust flex and camber.

“Still another contained oil that allegedly caused the ski’s performance to alter in relation to snow surface and temperature. There were bizarre little devices to prevent skis from crossing, and a pair of swiveling rods to keep the skis parallel at all times, so that the skier would never suffer the embarrassment of being seen vee-ing them in a stem.”

Exploring Vintage Ski World

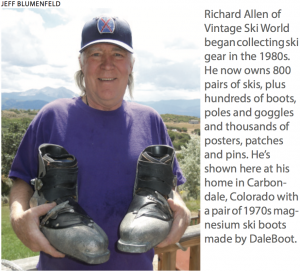

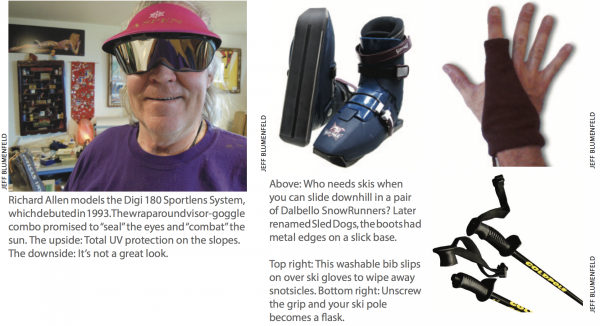

A leading connoisseur of crazy ski products is ISHA board member Richard Allen, 65, owner of Vintage Ski World, one of the largest private collections of ski memorabilia. Visiting his warehouse is a trip in itself: You drive uphill miles from Colorado State Highway 82 to reach a rustic five-acre hillside home and warehouse overlooking Mount Sopris and the Elk Range in Carbondale.

Allen, a former Aspen carpet cleaner, began collecting skis and other gear in the late 1980s, including a pair of handmade Norwegian wooden skis that his grandfather used in the early 1900s. Today his inventory includes 800 pairs of skis, including many in mint unmounted condition, plus hundreds of boots, poles and goggles, and thousands of pins, patches and posters.

Allen, a former Aspen carpet cleaner, began collecting skis and other gear in the late 1980s, including a pair of handmade Norwegian wooden skis that his grandfather used in the early 1900s. Today his inventory includes 800 pairs of skis, including many in mint unmounted condition, plus hundreds of boots, poles and goggles, and thousands of pins, patches and posters.

When two episodes of Mad Men and the 2010 cult classic Hot Tub Time Machine came looking for vintage ski gear, Allen provided the necessary props, still regretting to this day that he sold movie producers his best neon outfits.

His home is packed with snowshoe lamps, sled coffee tables, a wall of vintage ski boots, toboggan bookshelves, ski mirrors that he makes himself, and even toilet plungers made from ski poles. Enter his warehouse and you’ve stepped back into skiing history.

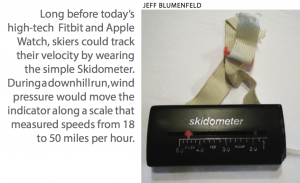

There’s the very analog Skidometer, “the Simple Practical Ski Speedometer.” You wear it on the left sleeve, move the needle to the forward position, then read your highest downhill speed in miles per hour. It was invented in 1972 by New York neurologist Dr. Asa P. Ruskin and sold for $5.95. In a precursor to today’s warnings about texting and driving, it sagely cautions, “Do not attempt to read speed while skiing.”

Allen’s collection also includes heavy 1970s-era magnesium ski boots from DaleBoot—a hinged magnesium shell with a rubber closure over the instep. If Herman Munster skied, you’d see him in these. Mel Dalebout’s magnesium shell was produced from 1969 to 1971 and was paired with his patented silicon-injection custom fit inner boot, precursor of all injected foam boots (the magnesium may also have been the world’s first three-piece or cabriolet shell).

Allen’s collection also includes heavy 1970s-era magnesium ski boots from DaleBoot—a hinged magnesium shell with a rubber closure over the instep. If Herman Munster skied, you’d see him in these. Mel Dalebout’s magnesium shell was produced from 1969 to 1971 and was paired with his patented silicon-injection custom fit inner boot, precursor of all injected foam boots (the magnesium may also have been the world’s first three-piece or cabriolet shell).

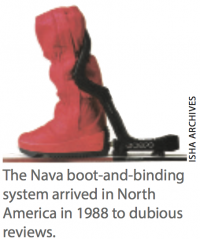

And there on a shelf was the Nava boot, part of a boot-binding system the likes of which were never seen before, according to Seth Masia writing in Skiing History (March 2005). Nava, an Italian manufacturer of motorcycle helmets and accessories, decided in the mid-1980s it needed a counter-seasonal winter product and designed this boot/binding system, introduced in Europe around 1986. It reached North America in 1988.

And there on a shelf was the Nava boot, part of a boot-binding system the likes of which were never seen before, according to Seth Masia writing in Skiing History (March 2005). Nava, an Italian manufacturer of motorcycle helmets and accessories, decided in the mid-1980s it needed a counter-seasonal winter product and designed this boot/binding system, introduced in Europe around 1986. It reached North America in 1988.

It consisted of a soft, warm, waterproof knee-high mukluk with an aggressive snow-walking tread. Hidden in the sole was a stainless steel lug that mated to a release binding on the ski; to provide edging power a spring-loaded lever arm was hinged to the back of the binding, Masia reports.

Ski journalist Steve Cohen writes in Ski Magazine (January 1990), “They tried to build the better mousetrap and succeeded. Unfortunately, they tried to sell them as ski bindings.”

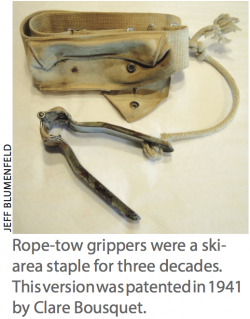

My tour continues with the Bousquet Ski Tow Rope Gripper, patented in 1941 (Skiing History, March-April 2017) and the Digi 180 Sportlens System that had a brief run as a combined visor and ski goggle in 1993. Selling for $49.95 ($85 in 2017 dollars), its brochure touts total vision protection by completely “sealing eyes” and “combatting” the sun with full UV protection” (assuming you didn’t mind looking like a robot).

Surrounded by all this skiing history, I ask the soft-spoken Allen why skiing attracts such product innovation. “The joy of being outside and skiing opens the mind and spirit to ideas, including dreaming up new inventions,” he says. “Budding inventors who ski have a lot of chair time to dream up products and ideas.”

Surrounded by all this skiing history, I ask the soft-spoken Allen why skiing attracts such product innovation. “The joy of being outside and skiing opens the mind and spirit to ideas, including dreaming up new inventions,” he says. “Budding inventors who ski have a lot of chair time to dream up products and ideas.”

A Flash in the Pan

Following my exploration of Vintage Ski World, I surveyed a number of ski industry journalists, retailers and manufacturers to compile a strange collection of ski products—the sport’s equivalent of the Mos Eisley Cantina, the famed bar scene in Star Wars.

When this unique gear first came out, inventors had high hopes of generating untold riches as skiers and riders flocked to retailers to be the first on their block to own one. Consider how many of these unusual ski products were a flash in the pan, but evoke plenty of smiles today.

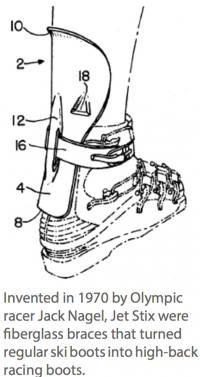

Skis are Overrated: Why endure the hassles of lugging skis around when all you need are slippery boots? That was the theory behind Dalbello SnowRunners, which were introduced in 1992 and covered that December in SKI Magazine. The plastic boots had metal edges on a slick, flat base and came in men’s, women’s and children’s sizes. They were later renamed Sled Dogs.

“Retailers acted like it was untreated radioactive waste as they saw people coming in and spending a thousand dollars less per person to get outfitted for a ski holiday,” says David Peri, a wintersports marketing consultant who was involved at the time.

To the bemusement of millions of viewers, Sled Dogs received their 15 minutes of fame during the opening ceremonies of the 1994 Winter Olympic Games in Lillehammer, Norway. You can still buy a pair online at sleddogs.com. (To see a video of a skier on Snow Runners, go to: https://youtu.be/_xYZmDwcWF8)

Snots Landing: Vail-based Snot Spot felt that your $160 gloves were missing a washable, slip-on bib to catch snotsicles. Launched in 2006, it didn’t have a good “run”—they’re now off the market.

We’ll Drink to That: Taos is famous for its martini trees—hidden bottles of martinis hanging from trees. But why hunt around for a tipple when you can carry one in your poles? That’s where the 2004 Coldpole comes in, the “Liquid Reservoir Ski Pole.” The grip unscrews to provide access to the natural storage capability of the pole—about eight ounces. And the opening is durable plastic so your lips never touch cold metal. A cleaning brush is provided with every pair, which oddly makes us feel a whole lot better about this crazy ski product.

Hot Dogging: Here’s a clever concept that dates to the early 1960s: to keep skiers warm, we’re going to light a campfire in their pocket. Jon-E Hand Warmers, carried in a flannel bag, ran on lighter fluid and sometimes caused rashes where it met the skin. They were made by Aladdin Manufacturing Co. in Minneapolis, a place that presumably knows a thing or two about cold. These days, you can find a used model—if for some reason you want one—on eBay or Etsy.

Hot Dogging: Here’s a clever concept that dates to the early 1960s: to keep skiers warm, we’re going to light a campfire in their pocket. Jon-E Hand Warmers, carried in a flannel bag, ran on lighter fluid and sometimes caused rashes where it met the skin. They were made by Aladdin Manufacturing Co. in Minneapolis, a place that presumably knows a thing or two about cold. These days, you can find a used model—if for some reason you want one—on eBay or Etsy.

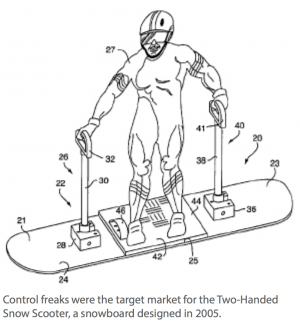

Sit Back and Enjoy the Ride: Jet Stix first appeared during the 1970–71 winter season. Invented by former U.S. Olympian Jack Nagel, who ran the ski school and shop at Washington’s Crystal Mountain, these were fiberglass braces that fit the lower calf above the boot and secured in place using the top boot buckle. Before these came along, kids were fashioning them out of Popsicle sticks and duct tape, according to Gregg Morrill of Vermont’s Stowe Reporter (February 9, 2012).

Sit Back and Enjoy the Ride: Jet Stix first appeared during the 1970–71 winter season. Invented by former U.S. Olympian Jack Nagel, who ran the ski school and shop at Washington’s Crystal Mountain, these were fiberglass braces that fit the lower calf above the boot and secured in place using the top boot buckle. Before these came along, kids were fashioning them out of Popsicle sticks and duct tape, according to Gregg Morrill of Vermont’s Stowe Reporter (February 9, 2012).

Jet Stix were designed to be high-backs for low-back boots like the Lange Comp, a year before Lange introduced its own high-back boot in response to Nordica’s high-back race boots. They were helped along by universal adoption of avalement (allowing the knees to flex and absorb bumps) in racing, and general toilet turns by recreational mogul skiers.

The product was a temporary fix until skiers could buy new boots and had a very short life cycle. Morrill believes Jet Stix were pre-empted by the next fad, which was short skis. (Not the short skis we have today which were engineered for their shorter lengths, but just shorter lengths of the popular skis of the day.)

Tinkle, Tinkle Little Star: Men might find it hard to relate, but Roffe “Tinkle Tabs” were quite a hit through the 1970s when one-piece suits were popular. When the snap on the sleeves of a women’s jumpsuit was undone, and the tab was fed under the belt and snapped back into place, the sleeves of that $500 outfit couldn’t fall on the wet floor of the ladies room—and we can imagine how disgusting that can be.

Tinkle, Tinkle Little Star: Men might find it hard to relate, but Roffe “Tinkle Tabs” were quite a hit through the 1970s when one-piece suits were popular. When the snap on the sleeves of a women’s jumpsuit was undone, and the tab was fed under the belt and snapped back into place, the sleeves of that $500 outfit couldn’t fall on the wet floor of the ladies room—and we can imagine how disgusting that can be.

Alas, when one-piece suits went the way of neon colors, it was buh-bye, Tinkle Tabs. Maybe they should have focused on a product to prevent ski gloves from falling into the toilet; it took years before resorts starting installing gear baskets in their stalls.

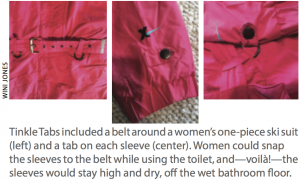

Two Hands Are Better Than One: Skiers aren’t the only ones t

o benefit from, er, innovation. With two handles and a set of bindings, the Two-Handed Snow Scooter was a snowboard designed in 2005 for control-freak master puppeteers—a very niche market, writes Illicitsnowboarding.com. It joins other crazy snowboard products including Lift Tethers and Legsavers for riding lifts.

Somehow skiing and snowboarding survived these get-rich-slow schemes. But driving north up Route 100 in Vermont, I sure wish someone would invent a better-tasting gas station hot dog. That would be a product that’s not too crazy at all.

If you have a favorite odd or crazy product you remember using, or still use, tell us about it. Post it on our Facebook page (facebook.com/skiinghistory) or email kathleen@skiinghistory.org.

Jeff Blumenfeld, an ISHA board member, runs Blumenfeld and Associates PR and ExpeditionNews.com in Boulder, Colorado. He is the recipient of the 2017 Bob Gillen Memorial Award from the North American Snowsports Journalists Association. For more information on Vintage Ski World, go to VintageSkiWorld.com.