International Skiing History Association names the year’s best works on sport’s heritage.

Watch video of the ISHA Awards program.

The International Skiing History Association this winter honors the Swiss Academic Ski Club and the year’s best ski-history books, films and websites published in calendar year 2019.

The Swiss Academic Ski Club (SAS) receives ISHA’s prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award for more than 90 years of promoting and preserving the history of the sport. Founded in 1924, its wide-ranging mission includes leading the Swiss alpine and nordic university teams, organizing races and events and publishing Der Schneehase, a highly regarded ski-history compendium. SAS Schneehase president Ivan Wagner accepts the award, which focuses on SAS accomplishments in documenting ski history through 39 deeply researched and illustrated editions of Schneehase since 1924.

ISHA also present its Stewardship Award to the Holding family for their decades-long commitment to preserving the history of the Sun Valley ski resort, which they purchased in 1977.

Established in 1993, the ISHA Awards are presented every year to creators of outstanding ski history books, films and DVDs, websites, museum exhibits and other works of creative media. The winners of this year’s ISHA Awards are:

ULLR AWARD Presented for a single outstanding contribution or several contributions to skiing’s overall historical record in published book form.

Skis in the Art of War By K.B.E.E. Eimeleus. Translation and commentary by William D. Frank, with additional commentary by E. John B. Allen

Skis in the Art of War By K.B.E.E. Eimeleus. Translation and commentary by William D. Frank, with additional commentary by E. John B. Allen

Kalle Bror Emil Aejmelaeus-Äimä (1882-1935) grew up on skis in Finland, when it was still a duchy in the Russian Empire. At age 17 he ran off to fight in the Boer War, on the losing side. He then fought in a South American revolution, became a sea captain, and joined the U.S. Army as a cavalry sergeant stationed in Texas. He then worked as a cowboy. Back in Europe in 1906, he entered the Imperial military academy in St Petersburg, became a Russian cavalry officer stationed near Kiev, earned a degree in archaeology (a cover for spying in Ottoman lands), taught skiing and fencing, and competed in the first modern pentathlon at the 1912 Olympics. That year he wrote Skis in the Art of War, in Russian, hoping to update Russian Army skiing tactics based on the Finnish model.

Eimeleus barely survived cavalry action in the Great War. After the Bolshevik Revolution, Finland declared independence. Eimeleus joined the Finnish Army to help win a civil war with the local communists. He joined Finland’s right-wing government as head of the War Office, as adjutant to two presidents, and later, as military attaché in London, Moscow and The Hague.

The new Soviet Army took skiing seriously, but not seriously enough: In the Winter War of 1939-40 the Finnish army, 20,000 strong, inflicted half a million casualties on unprepared Soviet troops. In response, the Soviet government organized a massive ski mobilization prior to the German invasion in 1941. The Soviet counteroffensive against Nazi Germany during the winter of 1941–42 owed much of its success to the ski battalions formed during the ski mobilization, and to Skis in the Art of War.

This new translation by William D. Frank, in collaboration with ISHA’s own E. John B. Allen, includes most of the original illustrations, plus essays on the historical context of European military skiing by the two collaborators. The footnotes contain a wealth of historical detail. Frank, a competitive biathlete in the early 1980s, is now a leading authority on the history of biathlon, especially in Russia. Skiing History published his fine history of Russian biathlon in the June 2009 issue. He expanded that work into a doctoral dissertation in history at the University of Washington, and it became his book Everyone to Skis!, which won the Ullr Award in 2015. –Seth Masia

Skis in the Art of War by K.B.E.E. Eimeleus. Translation and commentary by William D. Frank, with additional commentary by E. John B. Allen. 288 pages. Northern Illinois University/Cornell University Press, $37.95 hardbound; Kindle edition $9.95.

Skispuren: Internationale Konferenz zur Geschichte des Wintersports (Ski Tracks: International Conference on the History of Winter Sports) Edited by Rudolf Müllner and Christof Thöny

Skispuren: Internationale Konferenz zur Geschichte des Wintersports (Ski Tracks: International Conference on the History of Winter Sports) Edited by Rudolf Müllner and Christof Thöny

In December 2015, academic presenters from six countries discussed the development of alpine skiing and other winter sports at an international conference, with a section devoted to Austrian skiing. Skispuren is a collection of these 19 papers, with five in English. Annette Hofmann’s keynote address detailed Cristl Cranz’s leadership of German skiing in the 1930s and her role during the Nazi period. Christof Thöny gave us, for the first time, an insight into the importance of Arlberg ski pioneer Viktor Sohm. Michael Huber claimed—and I think he is correct—that Kitzbühel was the founding venue of downhill racing, rather than the much-trumpeted English race, the Roberts of Kandahar. Other presenters covered alpine ski touring in Sweden, British POWS interned in Switzerland during World War I, and a smattering of little-known subjects. With well-chosen illustrations and good bibliographies, Skispuren is a welcome addition to the modern analyses of winter sports. —E. John B. Allen

Rudolf Müllner and Christof Thöny (editors), Skispuren: Internationale Konferenz zur Geschichte des Wintersports (Bludenz: Lorenzi Verlag, 2019). Cost: €15 ($17) plus postage. Available from: www.lorenzi-verlag.at.

Unique and Unknown: The Story of Biathlon in the United States By Arthur Stegen

Unique and Unknown: The Story of Biathlon in the United States By Arthur Stegen

During the 2018 PyeongChang Olympic Winter Games, Arthur Stegen was at USA House talking to a fan who asked, “Biathlon? Whoever though up that sport?” An international competitor in the 1970s and a longtime coach for the US biathlon team as well as for Armed Forces Sports, Stegen took offense. He replied, “It wasn’t someone who thought skis were meant for sliding down banisters in slopestyle.” He went on to explain the origin of hunting on skis—a utilitarian purpose, he explained, unlike some of today’s more contrived events. He decided a book was in order. He had published a book simply titled Biathlon in 1979, prior to the 1980 Lake Placid Olympic Winter Games. An updated book would tie in the U.S. success in biathlon in the past four decades.

Thus was born Unique and Unknown: The Story of Biathlon in the United States, a definitive text on the 51-year history of the sport in the United States, with pictures from every era. In Part 1 Stegen answers the question “What is biathlon?” by detailing the history of the sport—including the evolution of shooting ranges and penalties—and how biathlon became an Olympic event (the concept of the complete athlete appealed to the IOC). Part II explains who the biathletes are, specifically, who represented the US on the world stage in biathlon, from soldier-athletes such as 1960 Olympian Larry Damon, through to 21st century stars Lowell Bailey, Tim Burke and Susan Dunklee. Although Stegen does not tell everyone’s story, he does touch on the sport’s most significant people, from America’s first female biathlete, Holly Beattie, to upcoming biathletes like Sean Doherty.

Stegen also explains what it takes to compete in biathlon and the future of the sport in the United States. Two appendices include the medalists in the U.S. national championships, from 1965 to 2017 for the men and 1980 to 2018 for women; and the medalists plus the U.S. competitors from the Olympics and world championships for all biathlon races, including relays, with times and penalties. Also included is a glossary of biathlon terms.

While the book might not hold the interest of what Stegen calls the “unaware” public, it’s a valuable compendium for those interested in all aspects of biathlon. –Peggy Shinn

Unique and Unknown: The Story of Biathlon in the United States, by Arthur Stegen. Great Life Press. $29.95 hardcover

Leisure Cultures and the Making of Modern Ski Resorts. Edited by Phillipp Strobl and Aneta Podkalicka.

Leisure Cultures and the Making of Modern Ski Resorts. Edited by Phillipp Strobl and Aneta Podkalicka.

We’re familiar with stories of how the stem-to-parallel ski teaching method of Hannes Schneider made its way from Austria’s Arlberg region to North America in the 1930s. And how the chairlift, invented around the same time at Sun Valley, Idaho, came to convey skiers up mountains around the world. What’s new is that these stories have become the subject of scholarly university research. How skiing spread around the globe has come under the microscope of the hot, relatively new academic discipline of “transnational” study . . . how culture is transmitted across national borders. Leisure Cultures and the Making of Modern Ski Resorts, just published in England, is a compendium of nine heavily researched papers that explore this topic.

Reading the book is daunting; in some places, it’s loaded with the turgid verbiage employed in academic writing. “The practice of recreational skiing can be regarded as a form of cultural participation and cultural practice,” writes Polish professor Stanislaw Jedrzejewski. “This expanded definition encompasses personal culture manifested through appearance, clothes, awareness processes, and modes of behavior that are regulated by ‘dissipated canons.’” (Editor’s note: “Dissipated canons” appears to refer to unprincipled or arbitrary authorities, or arbiters of taste.) Such passages aside, Leisure Cultures is a work of fresh and fascinating ski history. For example I learned from Professor Jedrzejewski how ski facilities in Poland developed, and failed to develop, over four decades under the Communist planned economy. Mindless incompetence was rampant. Transnationalism wasn’t in vogue.

By contrast, Austria’s Arlberg ski technique and teaching methods spread across the entire world. The disciples and descendants of St. Anton’s Hannes Schneider came to direct dozens of ski schools in North America and the Southern Hemisphere. The Bundessportheim in St. Christof was directed by Stefan Kruckenhauser, whose influence was worldwide. How it all happened is told in rich detail.

Chapters on Swedish cross country skiing and resort development in Australia and Turkey are similarly robust in factual detail. A chapter by two American authors explores how movies and popular magazines affected public perception of the sport in the 1960s. This is a serious book for serious ski historians. –John Fry

Leisure Cultures and the Making of Modern Ski Resorts, edited by Phillipp Strobl and Aneta Podkalicka. 2019 Palgrave MacMilland, London. $109.99, ebook $84.99 at palgrave.com/us/book/9783319920245. Individual chapters $29.95 digitally.

SKADE AWARD Presented for an outstanding work on regional ski history, or for an outstanding work published in book form that is focused in part on ski history.

Heja Persson!: Sámisk triumf i Vasaloppet (Go, Persson! Sámi Triumph in the Vasaloppet) By Isak Lidstrom

Heja Persson!: Sámisk triumf i Vasaloppet (Go, Persson! Sámi Triumph in the Vasaloppet) By Isak Lidstrom

Published in Swedish, this is the story of the Sámi cross-country skier Johan Abraham Persson (1898- 1971), the surprise winner of the 1929 Vasaloppet. And it’s the story of the Sámi contribution to the history of skiing in Sweden. The indigenous Sámi were the pioneers when Swedish ski sport emerged in the late 19th century. However, even within their own sport, the Sámi experienced racism. Persson grew up in Skierfa, in Lapland’s backcountry. His Vasaloppet victory, over 87 of Sweden’s finest skiers, was a breakthrough for Sámi cultural identity, and over the decades has assumed mythic proportions.

Reviewers in Swedish call this “a gem of a book,” for its portrayal of the cultural nuances of the race. The Vasaloppet, first run in 1922, was still a novelty, and drew participation by fewer than 100 top skiers – far from the 15,000 citizen-racers who start in the modern event. At the time, Swedish elites in the south of the country viewed skiing as a utilitarian activity mastered by farmers and other rural, working class people. Upper-class amateurs went in for sports with no practical applications: skating, curling, sledding. A cultural gulf yawned between Sweden’s prosperous southern and impoverished northern provinces, and the Sámi, who migrated across northern Finland, Sweden and Norway, weren’t even regarded as true Swedes. Persson came from a family of lake fishermen, whose fixed abode drew scorn from “authentic” reindeer-herding Sámi.

True, Swedes regarded Sámi as “natural” skiers, who didn’t have to train for the sport. Ironically, that stereotype led to an attitude that, because virtue lay in training and hardship, victory should morally go to a Swede. This sentiment paralleled the Olympic prejudice that amateurs were morally superior to people who made a living from sport. Persson, who trained by hunting wolves with his brother, had to travel 600 miles from Lapland to Mora, where the race was held. Lidström provides a colorful account of that trip, and of preparations for the race, and the dramatic race itself. At one point, the Crown Prince’s private train stopped, blocking half the field from crossing the track. Some racers felt this was a casual expression of the contempt felt by southerners for northerners. Persson took an early lead, but with no one to follow, got lost in the woods. He then had to overtake the local favorites and sprint to victory.

Isak Lidström is a sports historian and PhD candidate in Sports Science at Malmö University. His 2015 book Zorn, kyrkloppen och idrottsrörelsen (Zorn, Church Races and the Sports Movement), won an ISHA Skade honorable mention. –Seth Masia

Lost Ski Areas of the Berkshires By Jeremy Davis

Lost Ski Areas of the Berkshires By Jeremy Davis

The Berkshires of Massachusetts have long been known as a winter sports paradise. Forty-four ski areas arose from the 1930s to the 1970s. The Thunderbolt Ski Trail put the Berkshires on the map for challenging terrain. Major ski resorts like Brodie Mountain sparked the popularity of night skiing with lighted trails. All-inclusive resorts—like Oak n' Spruce, Eastover and Jug End—brought thousands of new skiers into the sport between the 1940s and 1970s. Over the years, many of these ski areas faded away and are nearly forgotten. Jeremy Davis of the New England/Northeast Lost Ski Areas Project brings these lost locations back to life, chronicling their rich histories and contributions to the ski industry.

Jeremy Davis is a skier, writer and meteorologist. Originally from Chelmsford, Massachusetts, he graduated from Lyndon State College with a degree in meteorology and has been employed at Weather Routing Inc. since 2000. In 1998, he founded the New England and Northeast Lost Ski Areas Project (www.nelsap.org), which documents the history of former ski areas throughout the region; the site won a Cyber Award for best ski history website from the International Skiing History Association (ISHA). In 2000, he was elected to the board of directors of the New England Ski Museum and continues to serve today. He is the author of four books: Lost Ski Areas of the White Mountains, Lost Ski Areas of Southern Vermont, Lost Ski Areas of the Southern Adirondacks and Lost Ski Areas of the Northern Adirondacks. Both Adirondacks books won ISHA Skade Awards. He also serves on the editorial review board of ISHA’s magazine, Skiing History. The author resides with his husband, Scott, in Saratoga Springs, New York, and is a frequent skier in the Berkshires.

Lost Ski Areas of the Berkshires, by Jeremy Davis. 240 pages. The History Press. $29.95 hardcover, $15 softcover, Kindle edition available.

Honorable Mention: Snowboarding in Southern Vermont: From Burton to the U.S. Open by Brian L. Knight

BALDUR AWARD A new category of awards presented for books that have not been written as ski histories, but possess valuable historical content.

Ski Inc. 2020 By Chris Diamond with Andy Bigford.

Ski Inc. 2020 By Chris Diamond with Andy Bigford.

This is a sequel to Diamond’s Ski Inc, a “part memoir, part business history of the modern ski resort,” which won a 2016 ISHA book award. Chris Diamond experienced firsthand the resort conglomerations over the past 30 years. Publicly traded Vail Resorts has come to own 37 ski areas, and privately owned Alterra owns 15. Pre-season sales of the Epic and Ikon passes are soaring. The two companies, along with 50-plus partner resorts that accept their passes, now account for half of all U.S. skier visits. And they maximize profits by owning retail stores, hotels, transportation companies and even local media.

The first half of the book recounts the ascendancy of Vail Resorts and the response to it in the formation of the competing conglomerate Alterra. Here is extraordinarily valuable new history, previously scattered through newspapers and the pages of Ski Area Management, now consolidated for the first time in a single account. Diamond provides histories of Boyne Resorts, POWDR ski areas, and Peak Resorts (recently purchased by Vail). He explains how independent areas are surviving and collaborating in offering season passes while raising the obvious questions about the challenges they face. Diamond concludes that all the changes, especially those instigated by Vail Resorts under CEO Rob Katz, have “helped re-energize a sport that had languished for years.” He suggests that resorts have made skiing so cheap and attractive that the sport will boom – but admits he’s seen no data to prove it will happen. In the years ahead it’s possible that bargain advance-purchase passes will cause skier-visit volume to rise. Unavoidable, though, is the observation that skier visits can rise statistically in volume even as the population of active skiers and snowboarders might simultaneously decline. It might happen if potential new skiers fail to research the myriad deals available, exposing themselves to the highest window ticket price in history. And the lift ticket is only a small part of the cost of skiing, which is obviously affected by the cost of buying or renting gear, transportation, lodging and food. SKI Inc 2020 is a book full of thoughtful conjecture, its pages spilling with information that will enrich the history of skiing for years to come. –John Fry

SKI Inc 2020 by Chris Diamond with Andy Bigford. $29.95 hardcover, 272 pages, 40 photos, index. Published by Ski Diamond Publishing, Steamboat Springs CO. Ebook at Amazon.

Alpine Cooking: Recipes and Stories from Europe’s Grand Mountaintops By Meredith Erikson

Alpine Cooking: Recipes and Stories from Europe’s Grand Mountaintops By Meredith Erikson

This is a lushly photographed cookbook and travelogue showcasing the regional cuisines of the Alps, including 80 recipes for the elegant, rustic dishes served in the chalets and mountain huts situated among the alpine peaks of Italy, Austria, Switzerland, and France. In Alpine Cooking, food writer Meredith Erickson travels through Europe’s Alps–by car, on foot, and via funicular–collecting the recipes and stories of the legendary stubes, chalets, and refugios. On the menu is an eclectic mix of mountain dishes: radicchio and speck dumplings, fondue brioche, the best schnitzel recipe, Bombardinos, warming soups, wine cave fonduta, a Chartreuse soufflé, and a host of decadent strudels and confections (Salzburger Nockerl, anyone?) served with a bottle of Riesling plucked from the snow bank beside your dining table.

Organized by country and including logistical tips, detailed maps, the alpine address book, and narrative interludes discussing alpine art and wine, the Tour de France, high-altitude railways, grand European hotels, and other essential topics, this gorgeous and spectacularly photographed cookbook is a romantic ode to life in the mountains for food lovers, travelers, skiers, hikers, and anyone who feels the pull of the peaks.

Meredith Erickson has co-authored The Art of Living According to Joe Beef, Le Pigeon, Olympia Provisions, Kristen Kish Cooking, and Claridge’s: The Cookbook. She is currently working on The Frasca Cookbook. She has written for The New York Times, Elle, Saveur, Condé Nast Traveler, and Lucky Peach. When not traveling, she can be found in Montreal, Quebec (with friends and family at Joe Beef).

Hardcover | $50.00 Published by Ten Speed Press Oct 15, 2019 | 352 Pages | 8-1/2 x 11 | ISBN 9781607748748

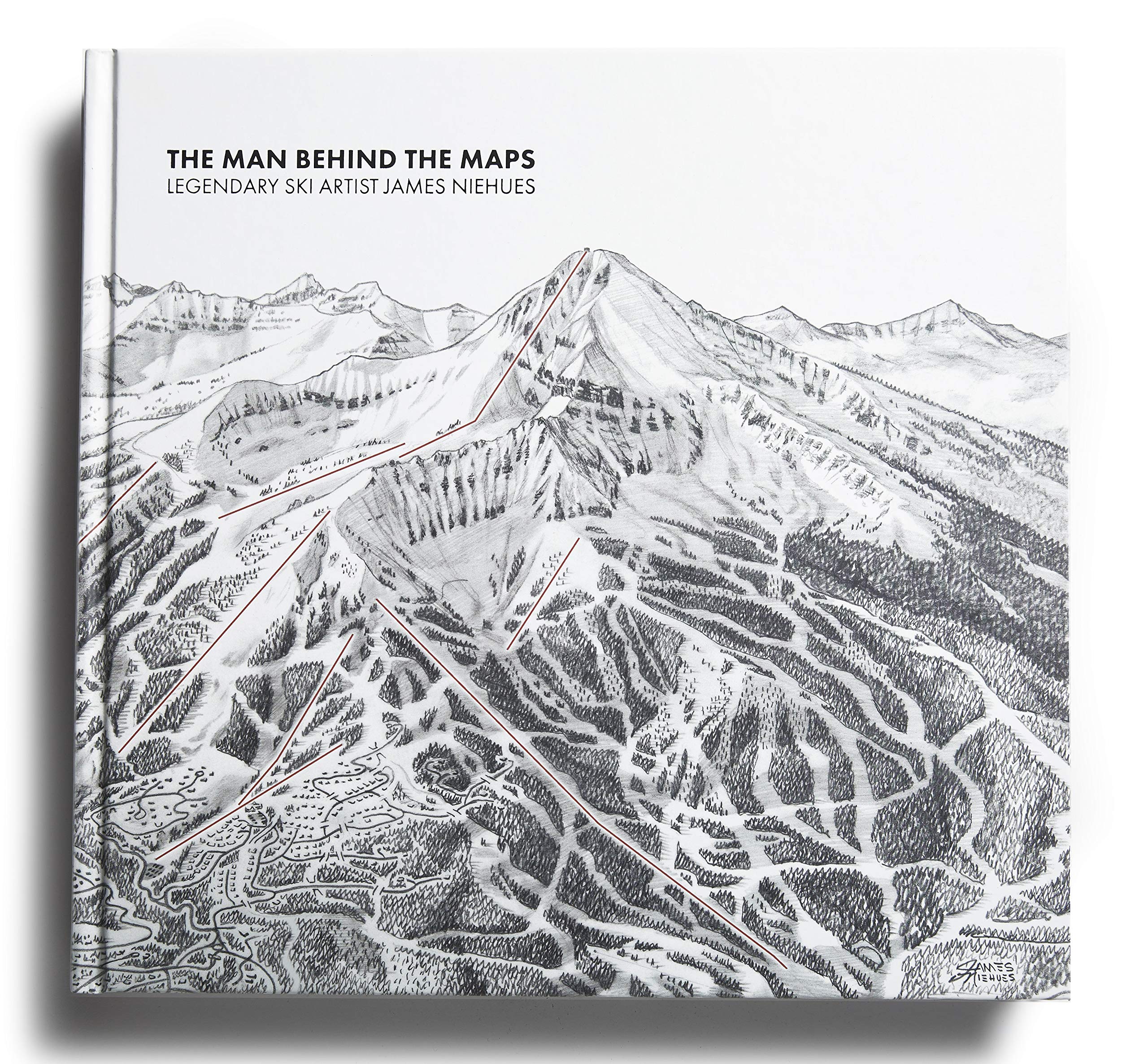

The Man Behind the Maps: Legendary Ski Artist James Niehues By Jason Blevins, with illustrations by Jim Niehues.

The Man Behind the Maps: Legendary Ski Artist James Niehues By Jason Blevins, with illustrations by Jim Niehues.

Ski map artist James Niehues has published a new coffee-table book that includes more than 200 of his hand-painted trail maps, with text by journalist Jason Blevins. With eight geographically themed chapters, the hardcover book is the definitive collection of the art created by Niehues during his 30-year career. In the modern digital age, Niehues may be the last of the great mapmakers. The book showcases his exacting process, in which he first captures aerial shots and then explores the mountain himself before painstakingly illustrating every run, chairlift, tree and cliff band by hand. Over the years, he has created maps for resorts across North and South America, Europe, Asia and Australia, with hundreds of millions of printed copies distributed to skiers on the slopes. “I’ve always enjoyed the challenge of fitting an entire mountain on a page. Mountains are wonderful puzzles, and I knew if I painted with the right amount of detail and care, they would last,” says Niehues. “A good design is relevant for a few years, maybe even a decade. But a well-made map is used for generations.” With Big Sky Resort chosen to illustrate the cover and a foreword by pioneering big-mountain skier Chris Davenport, the compilation includes trail maps from iconic destinations such as Jackson Hole, Squaw Valley, Alta, Snowbird, Aspen Highlands and Vail. The book is 11.5 inches tall and opens to a spread of 24 inches wide, the perfect size to showcase the biggest ski mountains in the world. Niehues went all-in on the production process, with Italian art-quality printing, heavyweight matte-coated paper, and a lay-flat binding.

FILM AWARD Presented for an outstanding contribution to the historical record of skiing in photographic or film/digital form

North Country Produced by Anthony Lahout, written and directed by Nick Martini

North Country Produced by Anthony Lahout, written and directed by Nick Martini

In Littleton, N.H., near Cannon Mountain, Lahout’s Country Clothing and Ski Shop has done business at the same location since 1920. Fourteen-year-old Herbert Lahout emigrated from Syria in 1898, and became a railroad laborer. He married his wife Anne in 1919 and the couple sold groceries from a horse-drawn wagon. The following year they moved the business into Littleton’s Old Grange Hall, and lived upstairs. Herb died in 1934 and, in the depths of the Depression, Anne was left to run the store with her kids Gladys, 14, and Joe, 12. Joe learned to ski, and the sport became his lifelong passion. After returning from service in the South Pacific during World War II, he added skis to the store’s inventory of hardware, dry goods, beer and groceries. Under the management of Joe’s three sons, and now of his grandson Anthony, Lahout’s developed into a full-service ski and outdoor store, with six locations in Littleton and Lincoln, half an hour south.

Joe died in 2016, on his 94th birthday. This 21-minute film tells the family’s story, with plenty of vintage ski footage from the Franconia Notch region. Lahout’s became integral to the history of skiing in New Hampshire. It’s a story of tough people thriving in a harsh climate – people who ventured out into the wider world but returned to the store to support their parents and grandparents. Director Nick Martini runs Stept Productions, making commercials for brands like Toyota, Oakley, Columbia, The North Face, Under Armour and even Tim Hortons. He grew up in the Boston area, skiing in New Hampshire. After earning his MBA, executive producer Anthony Lahout worked in finance before taking marketing jobs at Smith Sport Optics and Spyder Skiwear. He returned to Littleton in 2015 to take over the family business. See a clip from North Country.

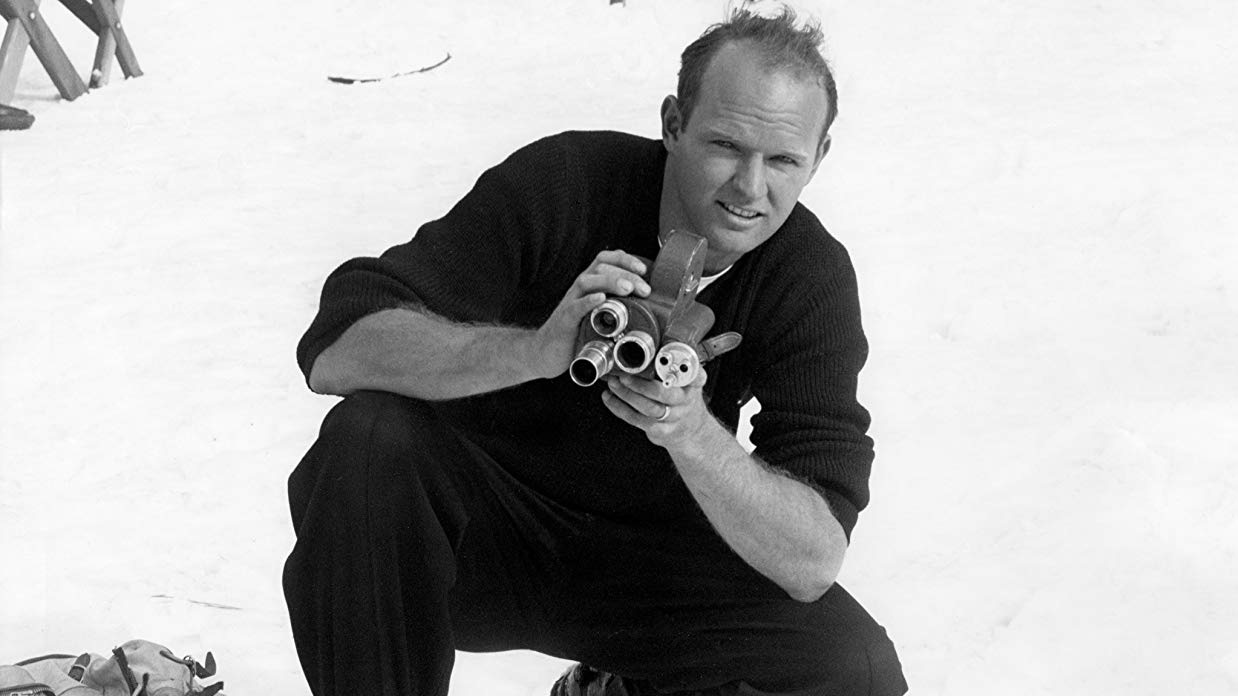

Ski Bum: The Warren Miller Story Directed by Patrick Creadon Produced by Joseph Berry Jr., Jeff Conroy, Christine O'Malley

Ski Bum: The Warren Miller Story Directed by Patrick Creadon Produced by Joseph Berry Jr., Jeff Conroy, Christine O'Malley

Ski Bum is a 90-minute review of Warren Miller’s extraordinary career, told through archival footage and one final interview with Warren himself. For decades, the ski season didn't really begin until the latest spectacular skiing film was released by Warren Miller Productions, filled with balletic, slow-motion mountain footage of death-defying ski and snowboard stunts. Ski Bum—titled after the moniker the Seattle-area legend often used for himself—celebrates the life and art of one of the most prolific sports-documentary pioneers. Credited with more than 750 sports films, Miller started as a surfer in his native Hollywood before moving to the Pacific Northwest to practically invent the winter-sports film genre. As Creadon's homage shows, Miller's simple 8mm movies from the 1950s snowballed into a 50-year commercial-film career that set the standard for audacious stunts. But success did not come without hardship; Miller used to promote his films on exhausting 100-city road tours, which took a toll on his family life and finances. Based on a 2018 interview the 93-year-old Miller gave shortly before his death at his Orcas Island home, Ski Bum explores the techniques used by the veteran filmmaker, who also served as cinematographer, editor, producer—and often live narrator—of his films. Using interviews with famous daredevil skiers, never-before-seen outtakes, and home movies, Ski Bum is a must-see for any ripper or shredder forever in search of the gnarliest powder.

Patrick Creadon is a director and cinematographer born in 1967 in Riverside, Illinois. He graduated from the University of Notre Dame in 1989 with a BA in International Relations. Creadon is married to his collaborator, producer Christine O'Malley; they co-founded their full-scale media production company, O'Malley Creadon Productions, which is based in Los Angeles and focuses on nonfiction storytelling.

Honorable Mention: Abandoned by Lio DelPiccolo, Sara Beam Robbins and Grant Robbins.

CYBER AWARD Presented for creating a website that contributes substantially to the preservation, distribution and expansion of skiing’s historical record.

DrySlopeNews.com By Patrick Thorne

Artificial slopes, using carpet or matting in place of snow, bring skiing to areas without reliable natural snowfall. Skiers have used them for over a century, but the earliest artificial surfaces manufactured specifically for skiing date from the 1950s. Since then, more than 1,000 have been built in more than 50 countries worldwide. The slopes come in lots of different shapes and sizes and there have been several different companies involved in their manufacturing over the past 70 years, so no two are ever the same. Dry ski slopes are essential for teaching millions of people to ski or snowboard. They can take the basic skills acquired on artificial slopes and ski at conventional ski resorts around the world. Indeed, the author claims, dryland slopes have been a major factor in the success of the global ski industry. Many established dry slopes have strong community support, enabling children and people with special needs to learn to ski or board as well as practice regularly. They have also bred some of the world’s best skiers and snowboarders who have gone on to World Cup and Olympic glory. DrySlopeNews.com includes a directory of existing and former dry slope operations, with a timeline history going back to the Vienna Schneepalast of 1927. The site is the creation of ski writer Patrick Thorne, who learned to ski on a dry slope as a school child in the late 1970s. Thorne has covered skiing from his base in the United Kingdom for more than 30 years. He operates the news site InTheSnow.com and a sister site, indoorsnownews,com, covering the snowdome universe.

Honorable Mention: From Chimney Corner: An Illustrated History of Slovenian Skiing by Aleš Guček