Why Racers Marry Their Ski Boots

Ski racers take extreme measures to get—and keep—a winning boot.

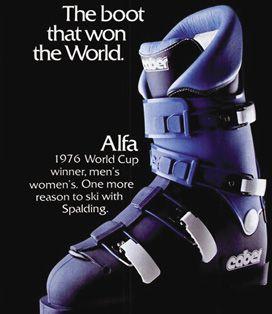

Ingemar Stenmark spent almost his entire World Cup career in Caber’s blue Alfa boot (top of page). He ran his first World Cup race, at age 17, in 1973. The Alfa was introduced in 1974, and Stenmark won his first slalom championship in 1975. Caber killed production of the Alfa in 1979, but when he ran his last World Cup race in March 1989, Stenmark still wore a banged-up pair of Alfas. Cindy Nelson, another Caber devotee, held onto her Alfas past her own retirement in 1985.

says Penny Pitou, “the pain was excruciating.”

Boot loyalty isn’t just a matter of athlete conservatism. Racers, and their boot-fitters, work hard to perfect performance and fit, a process that can take weeks or months of trial-by-error. Once victory is achieved in a customized boot, no racer wants to repeat the laborious process starting with a different model.

The objective of all the work: Get the boot shell to fit as closely as possible, often by squeezing feet into boots one or two sizes too small, with flex, cant and forward lean precisely calibrated. No cushy liners allowed to accommodate the bony protrusions of a particular foot, because a soft liner allows the foot to move inside the shell.

Later in her career, after Pitou had established herself as an international star, Austrian boot companies took foot measurements for custom-fitting boots they hoped she would wear. Eventually, Koflach came out with a Penny Pitou model, which Pitou believes was the first boot specifically designed for women. Earlier in her career, with no women’s boots available, she at one point acquired boots so large from a male racer that she had to stuff paper in them to prevent her feet from floating loosely in the extra space. She wasn’t alone. Her teammate Joan Hannah also used paper-stuffed boots, borrowed from ski-racing brother Sel.

Championship in this Lange. The steel

plate bolted on for slalom, off for downhill.

The boot still hurt like hell. Below, Kidd

dealt with the consequences. Paul Ryan

photo.

In the early 1960s, when Billy Kidd was rising through the ski-racing ranks, he used the hot-water method. Most top US racers at the time were given Heierlings (because coach Bob Beattie’s brother was the importer). Kidd filled each new pair with hot water to soften the leather, then laced his feet into the warm boots to allow the cooling leather to conform to the idiosyncratic shape of his feet—in what was a DIY version of future flow or injected boot liners. And he had to do it often. The leather broke down in a matter of six to eight weeks.

Across the pond, Jean-Claude Killy had plenty of help breaking in his leather Le Trappeur Elite boots. His friend, mentor and ski technician Michel Arpin suffered in new boots for a few days until the boots were “ripe.” Then Killy got a few races in while Arpin repeated the process with the next pair.

Plastic boots arrived at the advent of the World Cup circuit—actually, a year before, when the Canadian team showed up at the 1966 Portillo World Championships with a few pairs of Langes. From the start, the boots needed work to get the flex and forward lean right. Langes improved edging power immensely (they were part of Nancy Greene’s success), but didn’t conform well to any human foot, so they hurt like hell. The term “Lange bang” was born. Painful as the boots could be, skiers won five medals in Langes at the 1968 Olympics.

Kidd won his gold medal in combined at the 1970 World Championships with Lange boots, customized by master fitter Denny Hanson (later that year Denny and brother Chris left Lange to launch their own boot company). Denny fashioned metal plates for the backs of Kidd’s boots to add stiffness for slalom. He removed the plates for more flexibility for downhill.

Boot-fitting as an art form hit its stride with the introduction of plastic. Bootfitters could reshape shells by grinding and heating. Tools were invented to punch out tight spots. The durability of plastic meant that once the work was done, and the boots made to ski well, a racer could treasure that pair for years.

But plastic had its drawbacks, and not all plastics were created equal. When brothers Phil and Steve Mahre took center stage on the US racing scene in the late 1970s, Lange’s XL-R model was their boot of choice. Lange subsequently came out with a new and supposedly improved Z model, but “it was a different plastic, more brittle—a completely different feel,” says Phil. He stuck with his old XL-Rs. Good move. He went on to earn three overall World Cup titles.

Lange, of course, wanted to promote its newest technology but also wanted to keep its top athlete happy. The solution: Keep Phil in his XL-Rs but swap out the logos to make them look like Zs. (Both models were orange, so the deception was easily executed.) Phil took one extra measure to customize his fit: He replaced the Lange tongues with unanchored Garmont tongues, allowing them to float freely within the boot, held in place only by the snugness of the fit.

Loyalty to a boot can outlast any other relationship. Over 13 World Cup seasons, Franz Klammer used three different Austrian ski brands—but kept the same customized Dynafit boots. And World Cup and World Champion Tamara McKinney stuck with heavily modified Nordica GT boots—a model discontinued a year before she ran her first World Cup race. McKinney had unusually small feet and slim ankles. The GT cuff was easily detachable and lent itself to tailoring for her pipestem lower legs. When an injury ended her career in 1990, she’d been married to the same boot for more than half her life.