Jimmie Heuga - Jimmie Heuga, Olympic slalom medalist, MS healing pioneer

In 1949, the 1937 World Alpine Champion Emile Allais arrived at the newly-opened Squaw Valley to be ski school director. Allais spoke little English, and was happy to relax with another Frenchman on site, the lift operator Pascal Heuga. Heuga had a six-year-old son in tow. Little Jimmie followed Big Emile around the mountain. Imagine learning to ski by mimicking a world champion and his hot-skiing buddies, in the varied snow and profound steeps of Squaw Valley. Before he was 12, Jimmie Heuga was a nationally-ranked racer, and was traveling around the country to race and train with 18-year-olds like Buddy Werner. At 15, weighing less than 125 lb., he earned a berth on the U.S. Oympic training squad. At 17, after his first trip to Europe, he became U.S. national champion in slalom.

At 18, Jimmie joined Bob Beattie’s University of Colorado ski team, and began training for the 1964 Olympics. Beattie’s training routines involved hours of brutal wind sprints, and Heuga, still the smallest man on the team, earned a reputation as the toughest, hardest-working, most determined racer on the planet. At the Chamonix World Championships in 1962, he finished fifth in combined. Leading up to the Innsbruck Olympics, he regularly finished third and fourth in European giant slaloms.

In the Olympic slalom Jimmie started 24th but finished the first run second behind Austria’s Pepi Stiegler. Skidding in a hairpin on the second run, he was late for several gates, but was amazed to see that his second-place time held up – until his friend Billy Kidd came down. On the podium, it was Stiegler, Kidd and Heuga. At long last, American men had medaled in an alpine event. A week later, Jimmie won the slalom (beating Jean-Claude Killy) and the combined at Garmisch, becoming the first American to win the Arlberg-Kandahar combined.

After breaking a vertebra in the 1967 Wengen slalom, Jimmie scrambled back to finish that inaugural World Cup season sixth overall, ninth in slalom and third in GS – by far the best American standing. The following spring, he felt weak in training, and his vision was going fuzzy. These were the first signs of multiple sclerosis. After a tenth-place finish at the Grenoble Olympics in 1968, Jimmie retired from racing and took a job running quality control for the new Lange-Dynamic factory in Boulder. In 1970, at age 27, Jimmie was diagnosed with MS.

Through the ‘70s, Jimmie bounced around the ski industry from job to job, battling depression and suffering divorce. Against medical advice, he began a training regimen and found it helped him physically and mentally. The smile returned, and the work ethic. By 1980, he was preaching to other MS patients, and the gospel was this: “Take control. Be active. Do the best you can with what you have.”

In 1982, helped by Killy, Jerry Ford and a grant from the Vail Valley Foundation, Jimmie laid plans to launch the Heuga Center for the Reanimation of the Physically Challenged, in Edwards, a few miles west of Vail. The Center opened in 1984, supported by proceeds from the Heuga Express fundraisers. By 2002, the Express ran 26 events each winter, raising up to $1 million annually to run the Center’s five-day diagnostic programs. It was enough to take 150 patients a year, in groups of 25.

With success came acceptance of his program by the medical community. In 1987 Jimmie married Debbie Dana; they had three sons, Wilder, Blaze, and Winston.

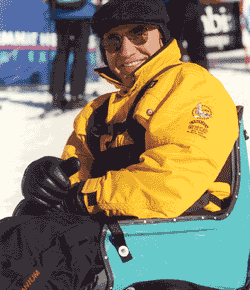

By 1996, MS had deprived Jimmie the use of his legs, but he cruised Vail regularly on a sit-ski. He spent his final decade in a nursing home in Louisville, ten miles east of Boulder, but traveled to the mountains several times each winter to ride the sit-ski, speak to Center patients and promote its programs, and attend ski industry events.

As his lifelong friend Billy Kidd pointed out, Jimmie Heuga never complained about his illness. He had a wide and loyal circle of friends and a world full of admirers.

Besides Debbie and sons, Jimmie is survived by his stepdaughter Kelly Heuga Hammill, by his father Pascal, now 100, and by his older brother Bobby, a retired English professor who also lives with MS. –Seth Masia

Billy Kidd’s Eulogy to Jimmie Heuga

It would be easy to be sad on this day, but Jimmie wouldn’t want us to be. Jimmie doesn’t have MS any more.

Jimmie didn’t suffer from MS. He thought of MS as just another challenge, another tough opponent, like Jean Claude Killy, or Pepi Stiegler.

Jimmie used to say: “Don’t feel sorry for me. I just have MS. Some people have REAL problems. Like maybe you can’t balance your checkbook…” Jimmie had a great sense of humor, and he loved to laugh.

Talking to Jimmie’s friends in the week, the conversations start out sad, saying “isn’t it too bad…” but within a few minutes, we’re talking about how lucky we were to have known him. Then, a few minutes after that, we’re talking about good memories, and how funny Jimmie was.

Racing Days

Jimmie was my hero. I grew up in Vermont; he was from California. My heroes were Andrea Mead Lawrence, Buddy Werner, and Jimmie Heuga. It was ironic that Jimmie was my hero because we were the same age. He was the best junior ski racer in America, and I wanted to ski like him.

We made the U.S. Ski Team together our last year in high school, and went to the World Championships, in Chamonix, in 1962. Jimmie and I and Bill Marolt, all age 18; plus Buddy Werner, Chuck Ferries, and Gordie Eaton. Our coach was Bob Beattie.

Coming from Squaw Valley, Jimmie loved to ski powder. The day of the World Championship GS, we had three feet of powder, and we all skied the powder in the morning, and then raced that afternoon. Three weeks before the World Championships, we raced in Wengen, Switzerland. The Lauberhorn is a men’s race, so there were no girls around. The French team had just heard about a new dance from America, called the Twist. Jimmie was the cool California kid, and he was an outstanding dancer. After the race, all of the French team — Killy, Francois Bonlieu, Charles Bozon — the best racers in the world — talked Jimmie into teaching them to Twist. So I just remember how funny it was, watching all the guys — no girls! — out there with Jimmie on the dance floor, doing the Twist. Jimmie loved to dance.

1964 Olympics

1964 Olympics, Innsbruck, Austria: Jimmie and I won medals together. We didn’t realize how much it would change our lives. If either of us had won a medal that day, it could have been just a lucky day. But because we won those medals together, and because Jimmie and I were not the favorites (Buddy Werner and Chuck Ferries were the favorites), winning those medals said the U.S. Ski Team was now a real team.

After the prize giving, Jimmie went back to his room at Olympic Village, where Buddy was his roommate. He was agonizing over what to say to Buddy, feeling that Buddy deserved to win that Olympic medal instead. He wanted to give his medal to Buddy.

This story points out that Jimmie was so gracious, kind, sensitive and gentle. And yet Jimmie was the toughest guy on the U.S. Ski Team. Bill Marolt has said, “Pound for pound, Jimmie was the toughest athlete I ever saw” — and Bill Marolt would know about toughness!

Jim Lillstrom said he remembers the ’64 Olympics, and how that moment shifted U.S. skiing into being a real team sport. Jimmie and I were teammates at the Olympics, and after that, we were teammates for life. Jimmie died on the same day we won our medals, 46 years to the day.

For most people, being an Olympian, being an Olympic medalist, being the best skier in the world, even for a day, would be enough.

But not for Jimmie. Jimmie went beyond the sport.

Just before the ’68 Olympics, Jimmie experienced the first symptoms of MS. So he raced in the Olympics with those symptoms, but his MS wasn’t diagnosed until 1970. The doctors said, “You only have a certain amount of energy, don’t waste it on exercise.” Jimmie listened to the doctors for a few years, then decided that he wanted to live his life as well as he could, even if meant his life was shorter. So he started exercising, and he felt better. Then he told some other people who had MS about exercising, and they felt better, too.

And that was the beginning of the Jimmie Heuga Center for the reanimation of the physically challenged.

President Gerald Ford gave Jimmie the initial seed money to start the Center. And then Jean-Claude Killy and a number of his Olympic friends, like Stein Eriksen, Phil Mahre, Bernhard Russi, plus Jan Helen, got together for the first Jimmie Heuga Express in Alaska, 26 years ago, to raise funds. That was the beginning of the Jimmie Heuga Express.

And speaking of friends, there are so may people in this room who have helped Jimmie along the way — too many to list, but I’d like to mention a few of them: Bill Chounet, Kim Kendall, Richard Rokos, and Dave Hardwicke, but most of all, Jimmie’s wife, Debbie. She was more than a wife, he was his assistant, his nurse, his strongest supporter, and she was his chief fundraiser, and best friend.

Two years ago, Jimmie received what could be his greatest recognition. He was inducted into World Sports Humanitarian Hall of Fame. Others in that Hall of Fame include Jackie Robinson, Arthur Ashe, and Pele. These are achievers and contributors who have gone way beyond their sport.

Lucky

I’ve been with Jimmie when people would come up, see him in his wheelchair, and say, “Oh, Jimmie, so sorry about your MS, you were an Olympic skier, and now you can’t ski anymore.” Jimmie would smile and say, “That’s OK, Jean Claude Killy can’t ski as well as he used to either….” Jimmie often said, “Don’t think about what you can’t do, do the best you can with what you have.”

Jimmie has said, many times: “I wouldn’t trade my life for anyone’s.” That sounds kind of surprising for someone in a wheelchair. But he said, “If I hadn’t had MS, I wouldn’t have met Debbie…or had the three wonderful boys I’m so proud of…or be invited to be on the President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports….”

So having MS actually gave Jimmie the opportunity to almost singlehandedly change the way the medical community thought about and treated MS.