The 1960s: In Like a Lamb and Out Like a Lion

Authored by Morten Lund

The 1960s arrived without flaunting any warning signs that the decade was going to usher in the notorious Sixties. The decade began in all innocence. Ski’s 1962 cartoon feature, a set of Bob Bugg sketches matched to Shakespearean quotes, published in the March issue, set the tone. These were cartoons about strain and sun rather than sex. The issue’s cover was a chaste-looking young woman in shorts—about as wild as things got, early on in the 1960s.

But there was a definite cultural thaw on hand. Even the agonizing war-guilt issue in Europe mellowed. Simplicissimus, a German humor magazine ran a ski cartoon cover of a German skier doing a double-take as he skids past a pair of the now-banned Nazi-era German national flag with its swastika emblem fluttering in the wind.

There was a thaw in technique as well. Early on, the decade saw the overthrow of the Arlberg rotation technique that had dominated the ski world since the early 1920s. The successful challenger was called “reverse,” the opposite of rotation. Instead of rotating the upper body in the direction of the turn, the skier—at least as it was then described—rotated the upper body away from the direction of the turn. For awhile. this new instruction confused everybody, but reverse, or rather its descendants, did finally prevail as “the American System.”

The new technique was in especially strong evidence at the 1960 Squaw Olympics— the first Winter Games held west of the Mississippi. Although top American skier Bud Werner broke a leg in training, costing the U.S. its first good shot at a men’s Olympic medal, the Games were a triumphal success of American organization and technology deployed under the chieftainship of Willy Schaeffler.

Among American contributors, Monty Atwater of the Forest Service impressed all the foreign nationals by blowing down any incipient avalanches with his recoilless rifles, which had already revolutionized powder skiing on the American continent.

IBM ran its first racing software program from a special building where its huge mainframe computers (a thousand times the size and less than a tenth the power of today’s average laptop) spewed out the combined standings right after every tenth racer crossed the finish line—just imagine it.

It was an aluminum Olympics. First of all most racers held onto their breakthrough aluminum Scott poles for dear life, not trusting them out of sight.

And the French had a double technical success: theoretician-racer Jean Vuarnet along with coach Georges Joubert had started the reverse revolution in the 1940s. Now he won the downhill with l’oeuf, “The Egg,” his aerodynamic stance—and won on French aluminum skis, the first skis not made primarily of wood to win an Olympic medal.

America’s Penny Pitou captured three silvers and Betsy Snite a bronze to make the Americans feel it was all worthwhile.

The triumph of aluminum was short-lived. The fiberglass ski came into its own, improving so rapidly that, in the 1962 FIS at Chamonix, Karl Schranz took two golds on fiberglass White Stars, moving Kneissl ahead of Sailer, Plymold, and Rossignol to build the first popular glass ski.

The most far-out revolution of the 1960s was the Clif Taylor short ski system, Graduated Length Method. Taylor was the first to use the power of cartooning to push a learning system. His 1961 Instant Skiing was spiced by cartoons making clear the advantages of short skis and the disadvantages of long ones.

The Professional Ski Instructors of America managed to discourage GLM even after it had been adopted by forty ski areas in the U.S. Parenthetically, in 1998, the system was revived by two of the big ski conglomerates pressed for cash flow and impressed that GLM consistently showed that half the novices returned for lessons versus 13% under standard long-ski teaching.

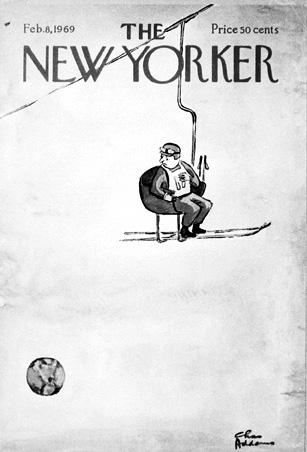

In the 1960s, with short skis and other innovations, skiing in general was getting easier. The 1960s saw the first surge of extensive grooming and snowmaking, expensive propositions reflected in the fast-rising price of lift tickets. But, fueled by the postwar economic boom that gathered more momentum as the decade wore on, skiers were mostly immune to sticker shock. Skiing began to penetrate as a status symbol. The popular Saturday Evening Post ran two ski cartoon covers in 1961. The New Yorker’s February 8, 1969 cover was a Charles Addams cartoon of a skier (eerily) being carried out of this world on a chairlift.

Another sign of the penetration came in 1962 with the appearance in Colorado of an instant Swiss village called Vail, whose fortunes were to carry it from sheep pasture to the top of the heap in North America within a decade. There were plenty of skiers to fill Vail. The ski population was zooming toward three million.

It didn’t hurt skiing’s prestige when the first U.S. racers to win men’s Olympic medals, Jimmie Heuga and Billy Kidd, took a bronze and a silver at the 1964 Winter Games in Innsbruck, Austria. The team was now under the management of Bob Beattie, who had supplied the necessary training and travel funds needed to win medals by greatly enlarging the financial support system of the U.S. Ski Team.

In 1964, Bob Lange produced the first plastic buckle boot, putting an end to the leather boot that inevitably stretched enough to encourage skis to wobble. The new boots were much more expensive, but times were good and skiers indulged themselves by switching to the best.

Skiing was on its way to becoming a sport of indulgence, a trend noted by James Riddell in his 1962 Ski Lore and Disorder with cartoons showing the sport as a new field of endeavor for an increasing number of skiers inclined to the apres-ski pursuit of the fortunate encounter.

The cartoonist Nitka appeared on the scene in 1964 in Ski with Nitka, done in the spirit of the times. His superb mastery of the odd situation included a skier bridging a crevasse with the aid of a helpless skier dangling upside down, and a unique cartoon of two-people-in-one-chair bringing the classic office liaison to the slopes.

In the 1960s, Bob Cram’s lean, repressed skiers populated a series of first full-page cartoon panels appearing in Ski as Cram’s Ski Life. The February 1966 panel had a condo bedroom scene as part of an essay on the instructor as seen by resort guests and others. Even New York State got into the budding zeitgeist with an advertisement in the February 1966 Ski: a portrait of a lady and her compact to show just what kind of girl might come strolling past a fellow who spent his weekends at New York resorts.

Ski ran its first ski nude in an article on Bear Mountain, California (a sort of visual pun on the title Ski Bear) and profiled the first Playboy ski resort in 1969. Given the new boots, the new poles, the new bindings, the new U.S. ski team, the new ski technique, the new grooming, the new snowmaking, and the new, accepting attitude toward the good life, by the time the end of the 1960s had ended, most skiers were perfectly aware that ski resorts were headed over the rainbow and it just wasn’t Kansas anymore. -- Morten Lund